|

Cover Story

Where is Assam?

Instead of accepting the

nationalisation of everything by political boundaries, we can

use geographical history to locate current social

realities.

by |

David

Ludden

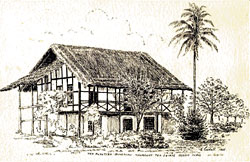

Tea

planters’ bungalow, Khorbhat tea estate, Assam, India

(E. Goodall, 1935) |

Assam is today a state of India and, as such,

an official region of a world entirely covered by nations and

encompassed by national maps. We have no choice but to locate

any region like Assam inside of national geography, for this

both controls our spatial imagination and conveys a specific

location, identity and meaning.

But other perspectives do exist. Despite the

seemingly universal authority of national geography, the

location of social reality is flexible. That Assam is part of

India is indisputable; but it is important to note that this

fact coexists with others that find different ‘locations’ for

Assam. Indeed, looking at any area’s geography in slightly

less conventional ways allows for the appearance of a

kaleidoscope of social realities. Such an understanding allows

for important new frames of reference for scholarship,

activism and policy-making.

The first step is to appreciate the political

nature of all modern maps. Territorial boundaries – as well as

social efforts to define, enforce and reshape them – represent

political projects rather than simple facts. The makers and

enforcers of boundaries use maps today to define human reality

inside of national territory. As a result, everything in the

world has acquired a national identity. We see the boundaries

of national states so often that they almost appear to be

natural features of the globe.

This virtual reality came into being only in

the 19th century, as various technologies for surveying the

earth, mass-printing, mass-education and other innovations

began to make viewing standardised maps a common experience.

Making maps, reading maps, talking about maps, and thinking

with mental maps became increasingly common with each passing

decade. By the 1950s, people around the world had substantial

map-knowledge in common. Today, we can reasonably imagine that

most people in the world share common map-knowledge because

they routinely experience various versions of exactly the same

maps. During the global expansion of modern mapping, national

territory suddenly incorporated all of the earth’s geography.

Though national boundaries only covered the entire globe after

1950, within a decade or two all histories of all peoples in

the world came to appear inside national maps, in a

cookie-cutter world of national geography. This has been the

most comprehensive organisation of spatial experience in human

history. Spaces that elude national maps have now mostly

disappeared from intellectual life.

Maps attain their form and authoritative

interpretation from both the political economy and the

cultural politics of mapping; the most influential people in

these processes work in national institutions, including

universities. State-authorised mapping is now so common that

most governments do not regulate map-making, but almost

everyone draws official lines on maps by habit anyway. Indeed,

this dynamic is so pervasive that few people ever even think

about it, yet it has covered the planet with the nation

state’s territorial authority. As a result, we are now

accustomed to seeing maps that nationalise topography by

erasing spaces on the edge of a nation’s identity. In India,

this includes several major spaces near Assam – areas in

Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh – which have become mostly blank

spaces in the country’s national view of Southasia. Every day,

TV and newspaper weather maps nationalise rainfall, wind and

the seasons, by enclosing them inside national boundaries.

This seemingly innocent nationalisation of nature makes it

increasingly difficult to visualise any world not defined by

national boundaries.

After understanding the political nature of

maps, our second step is to appreciate the extent to which

modernity depends on the idea of national territories. The

whole notion of modern statistics, for instance, could only

come into being inside ‘frozen’, unchanging geographical

spaces.

This freezing of blocks of space inside nations

had already begun by 1776 (when Adam Smith published The

Wealth of Nations), with the assumption that every nation’s

wealth belonged inside its national boundaries and under the

control of its national government.

Fixing regions in place inside national maps

brought to modern social life a newly rigorous, compre-hensive

order. Today, national maps describe the location of every

single thing, person and place on the planet.

National territory also heavily affects

cultural politics, both inside and across national boundaries.

Human identity everywhere is attached to national sites; in

those places, some people are always native, while others are

always foreign.

In the Indian context, Assam is a part of a

region officially called ‘Northeast India’ It has much more

geographical contact with other nations than with the Indian

mainland, however, from which it is most often described as

‘remote’. Assam is also grouped with state territories in

northeastern Southasia – described by the South Asia

Foundation as “…the eastern states of India, Bangladesh,

Bhutan and Nepal” – which has a definable population, GNP,

land area and trade history. This relationship alone allows us

to move our perspective around and to reconfigure Assam’s

geographical location. Following this strategy into the past,

step three in this process looks at geographical perspectives

that move along routes of movement, blending them together

over history.

This method is actually quite realistic. After

all, however natural, necessary and comforting it may seem to

assign everything in the world a fixed location, doing so

inside of firm boundaries can never succeed in creating a

stationary social order. Most of the time, everything in

social life is on the move, in a way that national geography

cannot accommodate. By considering how trends of mobility have

changed throughout history, we can locate Assam in a more

flexible geography.

Assam-in-Asia

Nature is a

good place to begin. An especially good place to begin is a

river, as defined by the naturally downhill movements of

flowing water. In such a water-view of the world, Assam lies

in Asian spaces defined by mountains, slopes and plains. These

monumental features channel the rains that arrive with Asia’s

longest, wettest monsoons and feed the extensive valleys where

rice became the dominant crop by around 1500 AD. In this wet,

river- and rice-fed Asia, human populations have historically

moved into and concentrated in river valleys and their

adjacent areas. Assam has long been a region of in-migration,

hosting new generations of settlers from prehistoric times to

the present day. With low-density mountains on three sides,

Assam is the eastern edge of the exceptionally high-density

Gangetic population zone that runs from the hills of Punjab to

the Bay of Bengal.

The impact of this water-view of Assam-in-Asia

becomes immediately clear on the geography of river

development projects today. All Indian rivers running through

Assam also flow into Bangladesh; throughout these watersheds,

people depend on the same water. Major dam projects disrupt

that geographical reality. The proposed Tipaimukh dam in Assam

and, more dramatically, India’s plan to divert Assamese waters

to parched Indian regions would reduce the flow of water into

the delta. It is little wonder that such plans arouse concern

(and outrage) in Bangladesh, which gets 80 percent of its

fresh water through 54 rivers flowing from India.

Assam also occupies a borderland of Asian

drainage systems, sitting astride a watershed that divides the

western trajectory of the Brahmaputra at the Patkai Range from

major drainages of Southeast Asia and southern China. Five

huge rivers define the major corridors of settlement and

mobility running from the Ganga basin across China, Vietnam,

Thailand and Burma. The Brahmaputra (or Jamuna in Bangladesh)

is the easternmost river of Southasia, but it is also the

westernmost in East Asia. In this context, India’s Northeast

is commonly found on maps of East Asia. Assam and the rest of

the Northeast, as well as the adjacent Chittagong Hill Tracts

in Bangladesh, can subsequently be seen as a western region of

East Asia, an eastern region of Southasia, and as a region

where South and East Asia overlap. It is this overlapping that

is impossible to accommodate on national maps; it thus

effectively disappears from the public conscious.

From ancient times, the NE-SE course of the

river valleys east of Assam has channelled human movement

inland through Southeast Asia and China. In Assam, important

such historical channels have included: the routes of the

ancient Khasi and Tai-Ahom migrations, which moved westward

from the Red River basin in Vietnam; the routes of opium

trade, with unknown origins but which extended from Bihar to

China; the imperial expansion of Burma; and the military

travels of the Chinese, Japanese, British and Americans along

roads from Assam to Yunnan, during the 1940s.

River routes have long connected Assam in each

direction. The major movements that decisively shaped the

region in early modern times (1660-1830) included: the Mughals

and British moving northeast from Bengal; the Ahoms moving

down the Brahmaputra basin; Burmese armies moving around the

Patkai and across the Nagaland ranges; and trans-Himalayan

forces coming south from Nepal, Bhutan, Tibet and China.

Before 1800, Indian Ocean routes seem to have

had less direct impact on the Brahmaputra valley than on other

Southasian regions comparably close to the coast. Most

importantly for its geographical history, however, by 1800

Assam lay at the intersection of Indian Ocean routes with

inland routes into interior East Asia. Thus, early British

imperial geographers believed with some justification that

Assam was India’s inland gateway to China. Opium and tea,

among other commodities, already travelled Indo-Chinese roads

through Assam. When Europeans ‘discovered’ India and China,

however, they did so at seaports; here they imagined all

societies as being attached to separate inland civilisations.

From this seacoast view of northeastern India, ethnic groups

in the mountains looked more like East and Southeast Asian

peoples than like those that dominated the Indian lowlands.

Thus, Europeans viewed East Asian-looking peoples in Northeast

India as marginal or even alien to the surrounding ‘Indic’

civilisation. These mountain ethnic groups, however, actually

represent the historical overlapping of social spaces,

defining Asia from the west and east at the same time.

British Assam

Our national

traditions of geographical knowledge do not pay equal

attention to all of the routes of human mobility that shaped

Assam. Indian historical geography focuses exclusively on

routes that run east-west along the Gangetic basin, where

dominant social groups have always identified Assam with

eastern frontiers. In the Indian national view, Assam has

always been an Indian frontier, always in the process of being

incorporated into Indo-Gangetic history. Even when the British

Empire began its northeast expansion from Sylhet and Cooch

Bihar, Assam still lay on cultural and political frontiers of

South and Southeast Asia.

|

Guwahati’s relations with New Delhi, even

today, represent a dynamic that began under the Gupta Empire

in the early centuries of the first millennium. Like the

Mauryas before them, the ancient Guptas carried their imperial

ambitions far from their homeland in Bihar, but also much

farther west than east – lands to the east of the Ganga basin

being considered undesirable. Gupta culture later influenced

the Assamese Kamrupa kings in large part through trade.

Indeed, the Buddhists who dispersed across eastern frontiers

flourished there for centuries, in part because trade, rather

than imperial power, extended across the water routes of

Bengal.

A thousand years after the last of the Guptas,

the strength of Ahom warriors in the Brahmaputra basin,

combined with the difficulty of forests and raging river

waters, largely kept Mughal imperialism at bay. During the age

of Ahom rulers in Assam, the Mughal Empire was rooted in the

far west. The renowned Mughal gardens derived from desert

ideals in Central Asia and Iran; Mughal homesteads blended the

cultures of Persia and Rajasthan. Lands of dense forests, deep

annual floods, rivers, tigers, elephants and fearsome mountain

warriors proved too difficult for the dry-land plains warriors

to conquer. These lands paid very little imperial taxation

anyway. As such, the Mughal padshah and his nobles mostly

conquered and sported on the fringes of forest tracts that

they left to local rulers, from whom they extracted as much

obedience and tribute as possible.

Assam became part of imperial India only after

the Mughals lost their grip in Bengal, as British imperialists

expanded inland from the sea with a combined force of

merchants, armies and Brahmans. Northeast of Calcutta, Mughal

highways pointed to Assam; but because Assam lay outside of

Mughal control, it remained so for early British India as

well. Only once the British conquered Assam in 1826 did the

area obtain – for the first time in its history – a firm

regional identity as a part of Indian imperial geography.

Until 1874, British Assam was part of a novel imperial

territory called ‘Bengal’, which included West Bengal, Bihar,

Orissa, Jharkhand, Northeast India and present-day Bangladesh.

British Assam always included the Brahmaputra and Barak river

valleys, as well as the Surma-Kushiara river basin of Sylhet.

After 1860, the tea industry spread across hills around these

rivers and enhanced control of the administrative unity of

Sylhet and Assam.

Until 1947, British Assam was an eastern

borderland of British imperialism, which tried to incorporate

Burma and never quite established full control over the

mountains between India and China. In the context of British

India, Assam’s Brahmaputra valley had special strategic

significance as a borderland between British India and

imperial China (until 1911) and Japan (1939-1945). In 1947,

Assam became India’s nearest borderland with revolutionary

China. In this strategic location, the US Army built the

so-called Stilwell Road in 1943 – running from Ledo in Assam

to the China-Burma road as a supply link with the Bengal-Assam

Railway for the US and British wars against Japan and, later,

the Chinese Communists (see Himal Sept-Oct 05 article on the

Stilwell Road). War along this road was intense. Recently,

Indian investigators found as many as 1500 graves from the

World War II era on the India-Burma border along the Stilwell

Road.

Partition and after

The

year 1947 dramatically changed the forces shaping Assam.

Partition and its fallout resulted in the cutting and

restriction of traditional routes around Assam, and introduced

major demographic changes. Together, these two forces give

Assam the shape and location we see today. Most importantly,

the formation of East Pakistan (and later Bangladesh) created

new national borders with a presumed hostile state to Assam’s

west and south. In Assam’s southeast, Sylhet was the only

region of British India where a referendum was held

specifically on the question of accession to India or

Pakistan; in 1947, the vote in favour of Pakistan separated

Sylhet from Assam for the first time since 1826.

Partition also exaggerated a process of change

in the cultural composition of the Sylhet population, which

had proceeded slowly for at least 50 years after the first

Indian census in 1871, when the Muslim and Hindu populations

had been roughly equal in number. After 1871, migration into

Sylhet farming regions increased the Muslim population with

every census. Between 1891 and 1931, people reportedly born in

the Bengal District of Mymensingh but living in Assam

increased from one-third to two-thirds of the population of

southern Assamese valleys, including Sylhet. Noting this

upward trend in migrant settlement, in 1931 the Assam Census

Report called Muslim Bengalis in Assam “invaders”. To defend

their territory against this ‘invasion’, the Assam Congress

resolved to move Sylhet out of Assam. The question of how to

regulate migration into Assam from Bengal dominated the state

political agenda in the 1930s and 1940s. After 1947, this

topic became a new type of national issue, with reference to

alleged threats to national security.

Migration continued to increase after

Partition, however, and remained high for three decades,

spurred in part by wars in 1965 and 1971. In the 1960s, the

total Sylhet population rose 60 percent as one lakh Muslim

Bengalis moved out of Assam into Sylhet’s Haor basin, where

open land was available. Sylhet’s population growth was most

dramatic in areas nearest Meghalaya and Tripura, where

migration produced completely new localities filled with

immigrants. In much of Sylhet, a new social formation emerged,

which ranked the cultural status of old and new residents – a

dynamic that continues today.

Although the ethnic composition of the

population had been a political issue in Assam since the

1920s, it raised its head again after 1950. Assam then shrunk

in size for two reasons: first, Partition cut out the

mostly-Muslim Sylhet; second, nationalist territorial claims

by ethnic groups produced the mountain states of Meghalaya,

Mizoram, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. The boundaries of

Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland are still contested

today, representing a tug-of-war over ethnic claims to natural

resources marked by state territory.

Trends in population change, the creation of

territorial borders and the mobilisation of ethnic politics

have indeed occurred throughout the Northeast’s much longer

history. This has historically moved people into more densely

populated areas that then expanded physically upwards, moving

from the lowland plains and valleys into the surrounding hills

and mountains; during that advance, large populations have

absorbed various ethnic and tribal groups. In the century

after 1880 (when statistics appeared for the first time), the

expansion of permanent cultivation proceeded at extremely high

rates in Tripura, Nagaland, Sikkim and Assam – faster than

almost anywhere else in Southasia, in fact. Most of this

expansion appears to be the result of lowland farmers

investing in land at higher altitudes. During this process,

Tripuris became a minority in Tripura, where mostly Hindu

Bengalis became dominant. A similar change occurred more

recently in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, where Muslim Bengalis

became numerically dominant, triggering resentment and revolt

among the region’s ethnic groups.

Such transformations of social space moved

investors and residents in 1947 into open areas still

available for agricultural colonisation. Huge tracts of land

remained free in forested regions of eastern and, especially,

Northeast India. Indeed, this became one of the last

agricultural frontiers in Southasia, where new farming

communities were able both to improve their living conditions

and to enhance national wealth. The physical expansion of

cultivated farmland remained the major source of increases in

Southasian agricultural production until 1960. Population

densities increased very rapidly in these frontier areas,

where, until 1880, people settled at an even greater pace than

into urban areas – although most upland agrarian frontiers

maintained very low population densities, which continues

today.

The stubbornness of territorial

anxiety

Against this backdrop, however, even in

regions typified over many centuries by extensive mobility,

national governments and popular movements worked harder after

1947 than ever before to close off and regulate traffic across

national borders. Their goals were twofold: to defend national

territory against foreign threats; and to suppress internal

disruption that might be fed by crossborder forces. India’s

Northeast became an ‘exposed’ territory, facing alien states

around most of its perimeter. Defending India’s borders meant

closing off the Northeast against crossborder threats. In

Assam, a regional political movement also tried to close

borders to alien immigrants, particularly from Bangladesh.

Today, the Bharatiya Janata Party again reiterates this

rhetoric.

New political efforts are now working against

the trend of national enclosure, however. Today, civil society

in Bangladesh is pressing its government and India to keep in

mind the real-life implications of rivers that run through

Assam and on into Bangladesh. State governments in the Indian

Northeast are also calling for a reopening of trade routes

along the old Burma-China Road, which would benefit landlocked

state economies that currently face international barriers on

three sides. At the moment, New Delhi is expressing

considerable interest in such plans.

Still, Assam’s continued official isolation

from non-Indian territories is a serious security concern for

the Indian government, now mostly due to the insurgent

problems within the country’s borders. In this respect,

India’s internal order problems are intimately linked with the

virtual impossibility of closing off Assam to the traditional

channels of human movement – routes that are much older than

any state in the region. This problem, of course, seems

common-place in today’s age of globalisation. While world

regions could benefit economically from simpler crossborder

connections, communities on opposite sides of international

borders would clearly benefit from common attempts to solve

trans-border problems. Nonetheless, national political and

cultural systems remain committed to strong border defences in

the fear of disturbing the coherence of their national

traditions. Indeed, the conflict between these two pressing

modern needs – territorial openness and closure – seems

increasingly difficult to reconcile.

So, where is Assam?

From

the above perspectives, a useful answer to the question of

‘Where is Assam?’ would be that Assam consists of all that has

left traces in the valleys and mountains around the

Brahmaputra and Barak rivers. In this view, locating Assam

requires that we trace the mobility of all of those elements

over the span of human history; after so doing, we can

discover the geography where those elements most meaningfully

overlap. While this would provide us with a good picture of

Assam’s location, it would not be one picture, but many –

leaving the problem of actual location open for debate and

endless research. Clearly there are numerous obstacles to

thinking about geography in this way. At the moment, national

borders simply don’t function like this (although people may

indeed be better off in regimes that would permit them freer

mobility).

|

Plans for a new Asian Highway would put Assam

at the centre of a new Asian transport system and would take

the state from the periphery to the centre of a new

territorial formation in Asia. But progress on the highway is

now stalled, due mostly to Indo-Bangladeshi disputes over

border issues, illegal immigrants, and terrorism allegations.

Against this backdrop of hopes for expanding mobility and

integration, however, it is worth remembering that new

national borders are, in the long span of history, typically

imperialist dreams. So it was in the days of the Guptas,

Mughals and British, and so too when the US Army built the

Stilwell Road to counter imperial Japan.

It is not surprising, then, that since 1945,

independent nations have generally increased the regulation of

traffic across their borders. Hostilities between India and

Pakistan have cut old routes of communication and mobility

more dramatically than almost anywhere in the world – this in

a region that had maintained highways from the Mediterranean

for a millennium. Elsewhere in Southasia, the Bengal-Assam

railway tracks from Guwahati to Dhaka were torn up at the

Cachar-Sylhet border in 1965. Nowadays, it is easier to

communicate by phone or mail between Dhaka and London than

between Dhaka and Guwahati.

In a world of national states it is thus worth

pondering: who is it that sponsors and argues for the opening

of geography and the crossing of national borders? Today,

increasingly diverse interests are engaged in this project –

including business groups, who are taking a lead in the

border-crossing movement and promoting the expansion of Asian

highways. Once upon a time, British imperial tea interests

financed the railway from Dhaka to Guwahati and fostered

Bengal’s integration with Assam to link tea estates to ports

and overseas markets. There is currently no major legitimate

economic interest in place to effectively instigate or finance

a major improvement in the Assam-Burma-China road and other

routes of transit across the mountains. Indeed, the largest

financial interests may be black- and grey-market trades, most

notably in the weaponry that is used in the region’s various

struggles. The impetus to open borders across mountains

spanning Nepal, China, Northeast India, Bangladesh and Burma

still seems weak when compared to the pressures of enclosure,

which remain significant. Still, this current dominance only

obscures the compelling ongoing mobility that continues to

locate Assam in the social reality of its Asian

surroundings. |