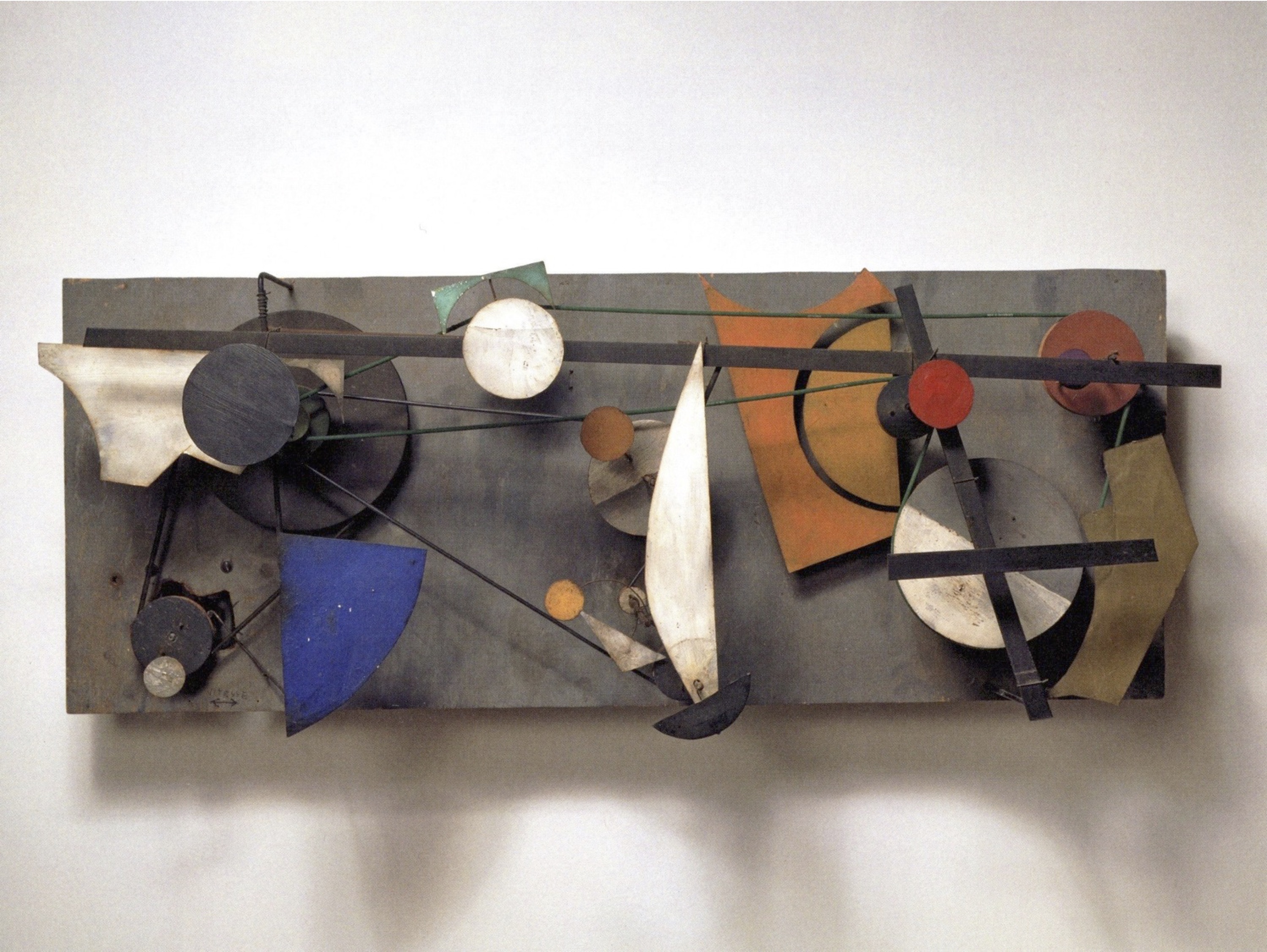

Jean Tinguely, Méta-Kandinsky I, 1956, Wood panel with nine differently shaped metal elements in different colors. Backside: wood pulleys, metal rods, rubber belts, electric motor. 39.8 x 103.2 x 33 cm

Tuesday, April 4, 2017 - 3:00pm to 5:00pm

David Rittenhouse Laboratory, Room 4E9, 209 South 33rd Street

Dissertation Defense - Marina Isgro, "The Animate Object of Kinetic Art, 1955-1968"

This dissertation examines the development of kinetic art—a genre comprising motorized, manipulable, and otherwise transformable objects—in Europe and the United States from 1955 to 1968. Despite kinetic art’s popularity in its moment, existing scholarly narratives often treat the movement as a positivist affirmation of postwar technology or an art of mere entertainment. This dissertation is the first comprehensive scholarly project to resituate the movement within the history of performance and “live” art forms, by looking closely at how artists created objects that behaved in complex, often unpredictable ways in real time. It argues that the critical debates concerning agency and intention that surrounded moving artworks should be understood within broader aesthetic and social concerns in the postwar period—from artists’ attempts to grapple with the legacy of modernist abstraction, to popular attitudes toward the rise of automated labor and cybernetics. It further draws from contemporaneous phenomenological discourses to consider the ways kinetic artworks modulated viewers’ experiences of artistic duration. Structured around case studies of four artists, the chapters draw from archival material and close examinations of artworks to elucidate diverse approaches to the kinetic. Chapter One examines Jean Tinguely’s early motorized reliefs, modeled on the paintings of the historical avant-garde, and argues that their shifting compositions enact an intensifying doubt about the principles of abstract composition. Chapter Two addresses Pol Bury’s exploration of perception in his slow-moving objects, linking the intense experiences of anticipation and suspense they generate to their Cold War context. Chapter Three treats Gianni Colombo’s flexible rubber and Styrofoam artworks, connecting them to the burgeoning field of Italian design and Umberto Eco’s nascent concept of the “open work.” Finally, Chapter Four investigates Robert Breer’s Float sculptures, and demonstrates how these works parody Minimalist principles while also intervening into cybernetic debates about behavior and intentionality in self-driven objects. While grounded in the postwar period, this project intersects with contemporary scholarly interests in performance, animation, and materiality.