Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital and the University of Pennsylvania 2

Summary.--Complex meaningful suggestions were given during various stages of physiological sleep as defined by EEG monitoring to 4 Ss high and 4 Ss low in hypnotizability. All the high hypnotizability Ss gave accurate behavioral responses while remaining asleep, but none of the low hypnotizability Ss did so. Specific response to sleep-administered suggestion was obtained only during Stage 1 periods.

Since the pioneer work of Aserinsky and Kleitman (1953) on the relation between dream report and stages of physiological sleep, classified primarily in terms of patterns of EEG activity and eye movements (Dement & Kleitman, 1957), there has been a marked increase in sleep research. Extensive work has been done with both animals and man on sensory capacity during sleep as measured by arousal thresholds. Work has also been done on simple discrimination capacity during sleep, and in man some information has been obtained on more complex activities during sleep.

Experiments on human discrimination and higher levels of integration during sleep can be logically, if somewhat arbitrarily, grouped on the basis of the temporal order of their design into three categories, as follows: (a) those involving response during sleep as a function of prior waking conditions (Wake-Sleep), (b) those involving response during wakefulness as a function of prior sleep conditions (Sleep-Wake), and (c) those involving response during sleep as a function of conditions during that sleep period (Sleep-Sleep). 3

Experimental work involving discrimination and higher activity in sleeping humans has involved considerable effort to test the retention during sleep of complex habits learned during wakefulness. Effort has also been made toward testing the recall during wakefulness of material presented during sleep. There seems, however, to be a lack of experimental attempts to determine the extent to which such complex interactions are possible during the sleep period itself. Perhaps there has been an underlying assumption that such interactions would neces-

1 Affiliated with Brandeis University.

2 This research was supported by Grant AF-AFOSR-707-65 from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. The authors wish to express their appreciation to E. Aserinsky for his helpful criticism.

3 A number of studies have been concerned with the effect of an intervening period of sleep on material learned in a prior wake state and tested during waking after the sleep period. These are, in our sense, Wake-Wake studies. They have been reviewed by Kleitman (1963) and will not be considered here.

629

630 J. C. COBB, ET AL.

sarily waken the sleeper. A brief review of recent relevant literature will illustrate this situation.

Wake-Sleep Studies

A number of studies have shown differential response to auditory signals during sleep either as a result of prior conditioning or instruction during wakefulness. Thus, Oswald, Taylor, and Treisman (1960) found that sleeping Ss were able to respond either behaviorally or electroencephalographically to their own name contained in a list of names played on a tape-recorder. Similar discriminations could be demonstrated to an arbitrarily chosen name not their own. Differential responses could also be elicited to a tonal signal to which S had previously been conditioned while awake when that signal was presented among other tones. The responses obtained were a hand clench, GSR response, or the appearance of the K-complex in the EEG. Evidence was found of discrimination not only during Stage 1 periods but also, with decreasing ease, at other sleep stages, including those showing extensive high voltage 1-cps activity.

Similar results have been obtained by Berger (1963 ), Granda and Hammack (1961), and Williams, Morlock, and Morlock (1963). Zung and Wilson (1961) were able to produce increased arousal to designated stimuli by offering financial rewards to their Ss.

In general, these studies have found that differential overt responses are best elicited at Stage 1 and hardly at all at Stages 3 or 4, although EEG changes showing alerting can be obtained at these levels.

Sleep-Wake Studies

The retention of material presented during sleep has been of particular recent interest in connection with attempts to utilize "sleep learning." Recent studies of this phenomenon that have employed EEG monitoring have found that both recall and recognition of material presented during sleep was possible but limited almost exclusively to levels of sleep showing the presence of alpha frequencies in the EEG, which would be equivalent to Stage 1 as currently defined (Emmons & Simon, 1956; Simon & Emmons, 1955; Simon & Emmons, 1956a; Simon & Emmons, 1956b).

Sleep-Sleep Studies

Work has been done on dream incorporation of external stimuli in EEG-monitored sleep. Typical findings have been those of Beigel (1959) and of Dement and Wolpert (1958) . The latter authors found instances of successful incorporation of stimuli in a variety of modalities during Stage 1 sleep with accompanying rapid eye movements. They used a flash of light, tones, and a fine spray of water as stimuli.

There seems, however, to be no specific experimentation addressed to the question of whether more complex informational transactions are possible with a

631 MOTOR RESPONSE DURING SLEEP

sleeping S who remains asleep. That such transactions may be possible is suggested by a long-standing tradition among workers in the field of hypnosis that a normally sleeping person can be given and will act upon hypnotic suggestions while remaining asleep (for examples see Bertrand, 1826; Bernheim, 1886). It has often been claimed that by the use of suitable suggestions normal sleep can be converted into hypnosis, and that this conversion can even be accomplished with otherwise hypnotically unresponsive persons (for a recent example, see Fresacher, 1951).

While there has been wide-spread agreement in the hypnotic literature on the existence of suggestibility during sleep, there has been no successful demonstration of response to sleep administered suggestions during electroencephalographically defined sleep. The need for reliable objective criteria of sleep such as the EEG now provides was recognized three decades ago by Hull (1933), who proposed using the patellar reflex as a then available indicant of the presence of sleep. While the recent study of Barber (1956) reported that suggestions during sleep were successfully responded to during sleep, no objective criteria, such as EEG, of the presence of sleep were used. The interpretation that Ss remain asleep during such suggestions, however, is called into question by a more recent study by Borlone, Dittborn, and Palestini (1960) employing EEG monitoring. In their investigation of the induction of sleep by direct suggestion and repetitive stimulation, these investigators reported the successful induction of EEG sleep patterns showing theta waves, and in one instance delta activity. They reported that such induced sleep could be turned into hypnosis by appropriate suggestions, but during verbal interactions between E and S, EEG patterns with waking alpha activity were shown, even though S had been instructed that he would remain asleep throughout.

Aims of the Present Study

The present investigation was designed to investigate the phenomenon of sleep-administered, and sleep-elicited suggestion. The specific goals of the study were as follows: (1) to determine whether Ss, when both receiving and responding to suggestions while ostensibly asleep, are indeed asleep as defined by current EEG criteria; ( 2) to determine during what stages of physiological sleep the suggestions could be successfully given and/or acted upon; (3) to determine whether sleep administered suggestion can, as reported in the older literature, be successfully used in Ss of low hypnotizability as a means of inducing a state of hypnosis.

PROCEDURE

Subjects

Eight paid volunteer male undergraduates served as Ss. All had previously participated in various experiments in the laboratory and had been tested for hypnotic responsiveness. Four of the Ss were deeply hypnotizable, readily showing posthypnotic amnesia, posthypnotic suggestion, and visual and auditory hallucinations. The remaining four were low in hypnotizability, showing at most some minor motor phenomena but no subjective altera-

632 J. C. COBB, ET AL.

tions. All Ss were asked to participate in a physiological study of sleep the exact nature of which was left unexplained. They were told that E might at times be in the room and speak to them as they slept. Each S participated in one experimental sleep session, conducted at night.

Experimenters

In order to test the generality of the phenomenon with a variety of operators, four different Es took part, each of whom tested one highly hypnotizable and one relatively unhypnotizable S. Es either had good interpersonal relationships with their Ss beforehand or attempted to establish them before the experimental session.

Recordings

S rested on a comfortable bed in a quiet, darkened room. Recording apparatus was in the adjacent room. Recordings were made with an Offner Type R 8-channel dynograph, using the following measures: occipital, parietal, and frontal EEG recorded monopolarly; vertical and horizontal eye movements recorded from the outer canthisand above and below the eye, respectively; palmar skin potential; electrocardiogram; and gross body movement. In general, the procedures recommended by van Kirk and Austin (1964) were followed.

Testing Procedure

After an initial rest period, the hypnotizable Ss were given an hypnotic induction of about 10 min. in order to obtain a sample of EEG activity to compare with their waking and sleeping EEGs. 4 After a second waking rest period, S was asked to go to sleep. The low hypnotizability group was also given a 10-min. attempted hypnotic induction period, although their response was minimal. No suggestions of sleeping were given, Ss being allowed to fall asleep naturally.

Two suggestions were administered to S while he was asleep. One suggestion was given during the first emergent Stage I period and was tested both during that period and during later stages of sleep. The second suggestion was given during a later sleep period other than Stage 1 (Stages 2, 3, or 4). It was tested then and again in subsequent Stage 1 periods.

Suggestions were chosen that required both a clearly identifiable behavioral output and a subjectively perceived effect. The subjective element was included specifically since it is felt to be the essential aspect of hypnotic phenomena (Orne, 1959). The suggestions were: (a) "Whenever I say the word 'pillow,' your pillow will begin to feel uncomfortable, and you will want to move it with your hand," and (b) "Whenever I say the word 'itch,' your nose will itch until you scratch it." When a suggestion was given, it was repeated 3 or 4 times before the cue word was given. A period of 30 sec. was allowed for the appearance of the response after each presentation of the cue. The cue word itself was also repeated several times, provided S remained in the desired sleep stage. The cue words were repeated also at sleep stages other than those during which they were originally given.

RESULTS

The primary results of this investigation may be summarized as follows.

633 MOTOR RESPONSE DURING SLEEP

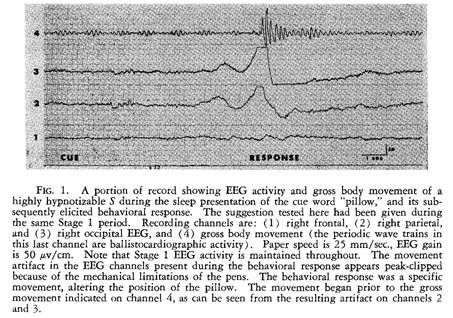

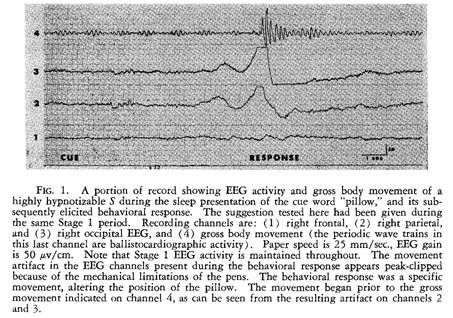

(1) All 4 highly hypnotizable Ss did respond behaviorally to the sleep-administered verbal suggestion and remained physiologically asleep. However, this only occurred when the suggestion was administered in emergent Stage 1 sleep. The sleep-suggestion response could be repeatedly elicited by repeating the cue word during the emergent Stage 1 period in which the suggestion was administered, as well as when tested in any subsequent emergent Stage 1 period. The responses were clear and distinct movements which appeared with short latency after the delivery of the cue word (see Fig. 1). When a cue word was

tested at other sleep stages, this usually produced arousal to Stage 1 sleep, after which S frequently responded to the suggestion; at other times, however, S remained in the stage he was in and did not show signs of arousal.

(2) All 4 low hypnotizable Ss failed to respond behaviorally to the sleep-administered verbal suggestion. 5 The administration of the suggestion or the testing of the cue word usually caused arousal with an accompanying waking pattern of EEG activity. Less frequently, low hypnotizable Ss continued sleeping with no behavioral or physiological response to the suggestion.

(3) Suggestions given Ss during sleep levels other than Stage 1 were not

634 J. C. COBB, ET AL.

successfully acted upon either when given or when tested later at another stage. 6 At least 30 sec. were allowed for S to respond after a suggestion or previously suggested cue word. In a few instances what appeared to be partial responses, movements perhaps resembling those suggested, were seen. However, since they could not be unambiguously identified as the movement suggested, they could not be counted as positive responses.

(4) When cue words which had been successfully acted upon during sleep were given the 4 hypnotizable Ss after the morning awakening, they were not acted upon again. Had they been acted upon, the situation would have been analogous to the phenomenon of posthypnotic suggestion. Post-sleep amnesia was tested but results were equivocal.

(5) The possibility of developing an hypnotic state in low hypnotizability Ss by means of sleep-suggestions could not be explored in this investigation, since all 4 of these Ss failed to show the sleep-suggestion phenomenon.

DISCUSSION

These results show the feasibility of using a Sleep-Sleep model for the investigation of complex, meaningful interactions in the sleeping S. They demonstrate the existence of specific behavioral responses during physiologically defined sleep to sleep-administered suggestions. The conditions necessary for the appearance of this phenomenon and its relationship, if any, to other suggestion phenomena remain to be explored.

The striking differences between Ss of high and low hypnotizability cannot be interpreted safely as a function of hypnotizability qua hypnotizability. The fact that the one group had experienced success in an hypnotic situation while the other group had experienced relative failure may have produced ongoing sets toward participation in suggestion-type experiments in this laboratory, and these in turn may have affected results. For example, the high degree of rapport between E and S assumed to be present in the hypnotic situation for the highly hypnotizable Ss may have been less developed with the low hypnotizable Ss. A related factor is the role of expectancy and training on this phenomenon. Low hypnotizability Ss have a history of failure in the hypnotic situation and may carry over an expectation of failure in like situations, including sleep suggestion. Additional training aimed at changing this expectation could influence later results.

The differential effect found for the two groups may also have been a function of such factors as the complexity of the suggestion and of the response asked for, e.g., easier responses might have been shown by both groups. Again, task complexity almost certainly was important in limiting the depth of sleep during which sleep-suggestion phenomena were found. Simple discriminations requiring minimal behavioral response for detection (such as the K-complex in the EEG record) have been demonstrated by other investigators, as mentioned previously, in deeper stages of sleep.

635 MOTOR RESPONSE DURING SLEEP

In summary, the present study indicates the existence under some conditions of the possibility of eliciting complex behavioral responses in sleeping Ss to meaningful sleep-administered suggestions. The parameters of this phenomenon, however, need elucidation. Studies defining the limiting factors of this phenomenon are under way at this time.

REFERENCES

ASERINSKY, E., & KLEITMAN, N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility, and concomitant phenomena, during sleep. Science, 1953, 118, 273.

BARBER, T. X. Comparison of suggestibility during "light sleep" and hypnosis. Science,1956, 124, 405.

BEIGEL, H. Mental processes during the production of dreams. J. Psychol., 1959, 43, 171-187.

BERGER, R. J. Experimental modification of dream content by meaningful verbal stimuli. Brit. J. Psychiat., 1963, 109, 722-740.

BERNHEIM, H. De la suggestion et des ses applications a la therapeutique. Paris: Doin, 1886.

BERTRAND, A. J. F. Du magnetisme animal en France et des jugements qu'en ont poster les societes savantes. Paris: Bailliere, 1826.

BORLONE, M., DITTBORN, J. M., & PALESTINI, M. Correlaciones electroencefalograficas dentro de una definition operacional de hipnosis sonambulica. Acta Hipnol. Latino Amer., 1960, 1(2) , 9-19.

CRASILNECK, H. B., & HALL, J. A. Physiological changes associated with hypnosis: a review of the literature since 1948. Int. J. clin. exp. Hypnosis, 1959, 7, 9-50.

DEMENT, W. C., & KLEITMAN, N. Cyclic variations in EEG during sleep and their relation to eye movements, body motility, and dreaming. EEG clin. Neurophysiol., 1957, 9, 673-690.

DEMENT, W. C., & WOLPERT, E. A. The relation of eye movements, body motility, and external stimuli to dream content. J. exp. Psychol., 1958, 55, 543-553.

DOMHOFF, G. W. Night dreams and hypnotic dreams: is there evidence that they are different? Int. J. clin. exp. Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 159-168.

EMMONS, W. H., & SIMON, C. W. The non-recall of material presented during sleep. Amer. J. Psychol., 1956, 69, 76-81.

FRESACHER, L. A way into the hypnotic state. Brit. J. med. Hypnotism, 1951, 3, 12-13.

GORTON, B. E. The physiology of hypnosis: 1. Psychiat. Quart., 1949, 23, 317-343. (a)

GORTON, B. E. The physiology of hypnosis: II. Psychiat. Quart., 1949, 23, 457-485.(b)

GRANDA, A. M., & HAMMACK, J. T. Operant behavior during sleep. Science, 1961, 133, 1485-1486.

HULL, C. L. Hypnosis and suggestibility. New York: Appleton-Century, 1933.

KLEITMAN, N. Sleep and wakefulness. Chicago: Univer. of Chicago Press, 1963.

ORNE, M. T. The nature of hypnosis: artifact and essence. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol.,1959, 58, 277-299.

OSWALD, I., TAYLOR, A. M., & TREISMAN, M. Discriminative responses to stimulation during human sleep. Brain, 1960, 83, 440-453.

SCHIFF, S. K., BUNNEY, W. E., & FREEDMAN, D. X. A study of ocular movements in hynotically induced dreams. J. nerv. ment. Dis., 1961, 133, 58-68.

SIMON, C. W., & EMMONS, W. H. Learning during sleep? Psychol. Bull., 1955, 52, 328-342.

SIMON, C. W., & EMMONS, W. H. EEG, consciousness, and sleep. Science, 1956, 124, 1066-1069. (a)

SIMON, C. W., & EMMONS, W. H. Responses to material presented during various levels of sleep. J. exp. Psychol., 1956, 51, 89-97. (b)

636 J. C. COBB, ET AL.

TART, C. T. A comparison of suggested dreams occurring in hypnosis and in sleep. Int. J. clin. exp. Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 263-289.

VAN KIRK, K., & AUSTIN, M. T. The electroencephalogram during all-night recording: technique. Amer. J. EEG Technol., 1964, 4, 53-61.

WILLIAMS, H. L., MORLOCK, H. C., & MORLOCK, J. V. Discriminative responses to auditory signals during sleep. Paper read at Amer. Psychol. Assn, Philadelphia, August, 1963.

ZUNG, W. W. K., & WILSON, W. P. Response to auditory stimulation during sleep. Arch. gen. Psychiat., 1961, 4, 548-552.

Accepted January 21, 1965.