Field, P. B., Evans, F. J., & Orne, M. T. Order of difficulty of suggestions during hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1965, 13, 183-192

ORDER OF DIFFICULTY OF SUGGESTIONS DURING HYPNOSIS 1,2

Veterans Administration Hospital, Brooklyn

Pennsylvania Hospital, The Institute, and University of Pennsylvania

Abstract: This study tests the hypothesis that successful response to

suggestion during hypnosis predisposes to further successful response, but failure

leads to subsequent failure. The Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility

was administered to 2 groups of 51 volunteer students. For one group, 8 of the

12 items were administered in the order easy-to-difficult; for the second group,

in the order difficult-to-easy. Total and 8-item mean scores, and frequency

distributions, did not differ significantly between groups. Except for the item

measuring posthypnotic amnesia, item difficulties for the 2 groups did not differ

significantly. Although the difficult-to-easy group was more amnesic, the 2

groups recalled a similar number of additional items when amnesia was "lifted."

The block of 4 easier items was relatively easier when preceded by a block of

4 harder items and, similarly, the harder items were relatively less difficult

if preceded by a block of easier items. The magnitude of this effect was small,

and the order effect hypothesis was basically not supported. Future research

should consider the S’s subjective impression of success and failure.

A variety of mechanisms have been postulated to account for the induction of hypnotic phenomena. One such hypothesis is that hypnotic techniques involve "shaping" procedures in which easily accepted suggestions are followed by increasingly more difficult ones. The initial suggestions in many induction procedures frequently take advantage of naturally occurring physiological responses. Thus, after S fixates on a specified point, suggestions of eyelid heaviness are timed to co-

Manuscript submitted December 17, 1964.

1 This research was supported in part by Grant Number MH 11028-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The study was carried out at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Harvard Medical School. The first author was a Mental Health Research Training Postdoctoral Fellow, and the second author held a Fulbright Travel Award, Research Category.

2 We wish to thank Lawrence A. Gustafson, Ulric Neisser, Donald N. O'Connell, Emily Carota Orne, and Ronald E. Shor for their helpful advice and critical comments during the preparation of this manuscript.

183

184 FIELD, EVANS AND ORNE

incide with the point at which S becomes aware of the fatigue accompanying fixation.

Particularly strong in the clinical literature is the impression that successful response to one suggestion predisposes the individual to succeed with a subsequent, more difficult suggestion. The induction process has been conceptualized in terms of S’s ability to respond to progressively more difficult items. It has been proposed that failure to respond to a suggestion lightens the depth of hypnosis. In other words, failure to respond to a suggestion may increase the probability of failure to respond to subsequent suggestions. The clinically-oriented procedures described by Erickson (1952) and Meares (1960) provide excellent examples of this approach to inducing hypnosis.

Similar experimentally-oriented descriptions of the induction process include Hull's (1933) homoactive and heteroactive suggestibility effects, Weitzenhoffer's formulations (1953), and the systematic verb conditioning approach of Welch (1947), and of Corn-Becker, Welch, and Fisichelli (1949). More recently, M. Orne (1961) proposed to induce hypnosis in recalcitrant Ss by means of a "magic room" which would, by physiological means, guarantee that certain “suggestions” were experienced: for example, an unseen diathermy machine would ensure that S’s arm actually would become warmer as such a suggestion is administered.

In spite of the popularity of the formulation that successful response to suggestion predisposes toward further success, there is little empirical evidence available to evaluate this hypothesis. Furneaux (1964) reported greater responsiveness to the heat illusion suggestibility test when it was preceded by training trials in which the increasing heat was actually experienced, compared to a similar test which was not preceded by reinforced training trials. Recent standardized measures of hypnotic susceptibility (e.g., Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1959; Shor & E. Orne, in press) present relatively easy items before more difficult ones. Reporting an unpublished study using the Stanford Profile Scales of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Forms I and II (Weitzenhoffer & Hilgard, 1963), Hilgard, Lauer, and Morgan (1963) state: "There is very little demonstrable item-order effect within a scale of the difficulty level of Forms I and II" (p. 13).

The aim of this investigation is to provide preliminary evidence about the widely held clinical belief that successful response to hypnotic suggestions leads to subsequent successful response to more difficult suggestions, while failure to respond to a suggestion increases the probability of failure on subsequent suggestions. If this effect is as striking as these formulations suggest, it should be testable by com-

185 ORDER EFFECT DURING HYPNOSIS

paring two orders of item-administration on a standardized measure of susceptibility to hypnosis. The percentage of Ss passing various items, and hence Ss' total scores, should differ when the items are administered from the easiest to the most difficult, compared to an administration of the items in reverse order. The hypothesis is tested in this study by administering the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Form A (Shor & E. Orne, in press) to two groups; one group being administered selected items from the scale in increasing order of difficulty, the other group being administered the same items in reverse order of difficulty.

Method

Subjects

Paid volunteer Ss between 18 and 25 years old were obtained for a psychological experiment by advertisement in college newspapers and on college bulletin boards. They were not told that the experiment involved hypnosis until they telephoned the laboratory for an appointment. The 69 male and 33 female Ss were tested in 12 groups of between 6 and 10 members. Allocation to test sessions depended on S’s availability. The testing order for the two forms of the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility (HGSHS:A) was determined by using a table of random numbers. There were 51 Ss in each of the two experimental groups. After the group test of susceptibility to hypnosis, Ss completed several paper-and-pencil personality inventories.

Two Forms of HGSHS:A with Altered Item Order

Two new tape recordings were prepared from the standardized taped version of HGSHS:A. The difficulty level of each item was determined from the normative data reported by Shor and E. Orne (1963).

The HGSHS:A is constructed so that items 1 and 2 are an integral part of the standard procedures inducing hypnosis. Consequently, it was not possible to alter the order of administering these items. Similarly, items 11 and 12 are based on posthypnotic performance. The remaining items, numbered 3 through 10 in the original HGSHS:A, were rearranged in the order easy-to-difficult. A second tape was made on which these items were presented in exactly the reverse order, difficult-to-easy.

Except for the altered item-order, the test was administered according to standard procedures. Appropriate response booklets were prepared which incorporated the altered item order but which were otherwise identical in format to the standard HGSHS:A booklets (Shor &

186 FIELD, EVANS AND ORNE

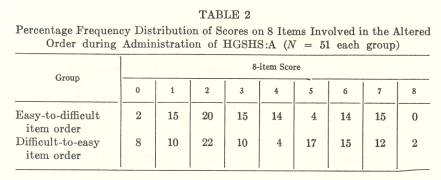

E. Orne, in press). The actual order in which the items were administered to the two groups, as well as the correct order in the standard form of HGSHS:A, is presented in Table 3.

Results

Distribution of Total Scores and Order Effects

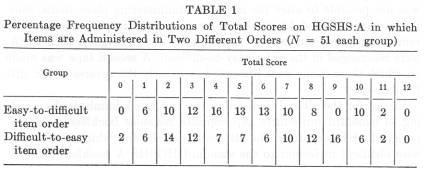

The percentage frequency distributions of total scores (12 items for the group administered easy-to-difficult items, and for the group administered difficult-to-easy items, are presented in Table 1. There is no significant difference between the means of easy-to-difficult and difficult-to-easy orders of administration (5.25 ± 2.63 and 5.59 ± 3.04 respectively; t = 0.60; F = 1.34). The dispersion of scores does not differ significantly between groups. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of the differences in the overall distribution of total scores is insignificant (C.V. = .79).

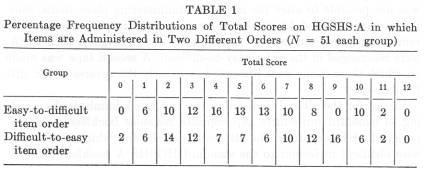

A comparison of the total score distribution includes scores on the four items which were administered to both groups in the same order as in the standard HGSHS:A. Eliminating these four items, the frequency distributions of scores on the eight items affected by the manipulation of item order are presented in Table 2. The respective means and standard deviations for the easy-to-difficult order group (3.69 ± 1.91) and the descending order group (3.76 ± 2.06) do not differ significantly (t = 0.20; F = 1.16). The eight-item score distributions do not differ significantly (Kolmogorov-Smirnov C.V. = 0.69).

It is concluded that the order of difficulty of administering items of HGSHS:A has no significant effect on the distribution of total scores.

Item Difficulty and Order Effects

The percentage of Ss passing each item is presented in Table 3. Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests of the difference between item difficulty across all 12 items, and across the eight items for which order of ad-

187 ORDER EFFECT DURING HYPNOSIS

ministration was altered, are both insignificant (C.V. = 0.75; C.V. = 0.50, respectively).

Chi-square tests of the difference in difficulty for each item between the two orders of administration are also reported in Table 3. There were significantly more Ss who passed Item 12:Amnesia, in the difficult-to-easy group (19 out of 51) compared to the easy-to-difficult group (only 8 out of 51; x2 = 5.04, p < .05). Differences between item difficulties for the remaining 11 items are insignificant. The combined chi-square probability testing the overall significance for the 12 items is insignificant (p < .30).

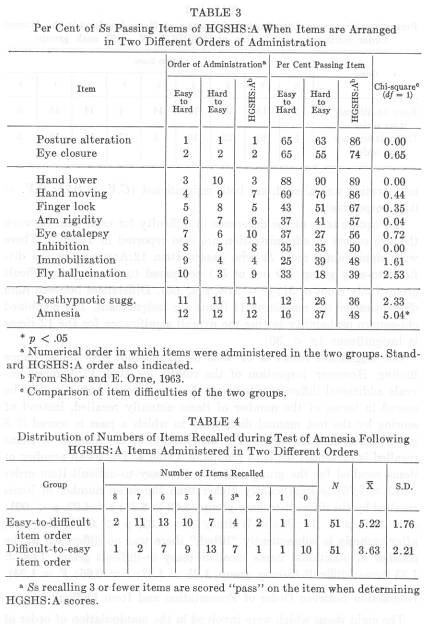

One significant result in 12 tests of significance may be a chance finding. However, inspection of the results for Item 12:Amnesia reveals additional differences between the two groups. Amnesia may be scored in terms of the number of items actually recalled, instead of scoring by the test manual dichotomy in which a pass is scored if S recalls three or fewer items. The distribution of the number of items recalled is presented for both groups in Table 4. The mean number of items recalled for the group tested in the easy-to-difficult item order (5.22 ± 1.76) is significantly higher than the mean number of items recalled by the difficult-to-easy group (3.63 ± 2.21; t = 4.02, p < .001; F = 1.58, p < .10; Mann-Whitney z = 3.82, p < .001). However, after amnesia is subsequently "lifted," there was no difference in the number of additional items recalled (easy-to-difficult group, 1.08 ± 1.23 items; difficult-to-easy group, 1.25 ± 1.37; t = 0.66; F = 1.24).

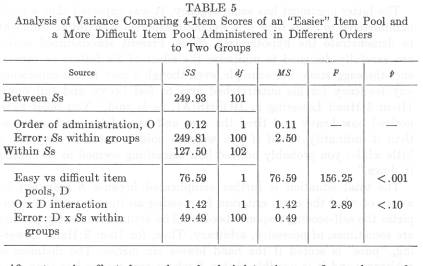

Interaction Between Order of Presentation and Item Difficulty

The eight items which were involved in the manipulation of order of administration may be divided into two pools of four "easier" and four "harder" items. Two scores were derived for each S, both ranging from 0-4, one for the easier block of items, and one for the harder block of

188 FIELD, EVANS AND ORNE

items. A double classification, split-plot analysis of variance computed on these scores is summarized in Table 5.

The significant item difficulty main-effect confirms that, for both groups, one item pool is easier than the other item pool. The insig-

189 ORDER EFFECT DURING HYPNOSIS

nificant main-effect for order of administration confirms the results summarized

in Table 2, that the overall eight-item score distributions do not differ. However,

the interaction effect is significant (p < .05, one-tail), indicating that

a block of relatively easy items are even easier if they have been preceded

by harder items than when administered before the harder items, and conversely

that harder items are relatively easier if they are preceded by a block of items

which are easily passed by most Ss. Another way in which these data can be seen

is to say that items which occurred later in the session tended to be more readily

passed than items which occurred earlier regardless of their intrinsic difficulty.

Discussion

The results of this investigation do not support the widely-held belief that success breeds further success, and that failure predisposes to failure in the induction of hypnotic phenomena. Only weak evidence was found supporting any effect produced by the order of difficulty in which items are administered during a standardized test of hypnotic susceptibility. Without attempting a post hoc rationalization of these results, it would seem that one of three conclusions is suggested: (a) order effects of item difficulty do not occur; (b) the relative importance of success and failure may refer to the induction phase of hypnosis (upon which these results do not bear) rather than testing the limits of S’s hypnotic experiences (Erickson, 1952); (c) the effects of success and failure may not be sufficiently strong to become manifest on a standardized test such as the one adopted.

190 FIELD, EVANS AND ORNE

The latter argument has some cogency. It was expected that a scale administered to Ss as their first hypnotic experience would be sufficient to demonstrate the hypothesized effect. Present standardized scales are carefully designed to minimize the effect of S’s failure to experience the suggestion. For example, even though S may fail to experience any tendency for his outstretched arm to feel heavy and fall down (Item 3:Hand Lowering in HGSHS:A), he is told, "You must have noticed how heavy and tired the arm and hand felt; much more so than it ordinarily would if you were to hold it out that way for little while; you probably noticed how something seemed to be pulling it down."

The total situation is further complicated because S may not be aware of what the exact criterion for passing an item is until he completes the self-scoring response booklet. The actual criteria for passing are sometimes, of necessity, arbitrary. Thus, for Item 3:Hand Lowering, "pass" is scored if the hand lowers six inches. The distance is arbitrary, and it is possible that a S whose arm moves less than the distance could be much more subjectively convinced of the efficacy of the suggestion than another S whose arm moves more than six inches, but who may be more aware of the accompanying natural physical strain produced when the arm is held extended. There may be a discrepancy between S’s self-perception of success and failure compared to the objective criterion of success and failure, particularly since S does not necessarily know what the objective criterion is, and since his response, however small, is encouraged as a successful one by the instructions. Future research will need to take into account the S’s perception about the success or failure of his own performance before providing a complete answer to the order-effect hypothesis.

In spite of these recognized limitations in this design, it was expected that the results would produce greater order-effects than were obtained. When items involved in the manipulated order of administration were divided into a pool of four "easy" and four "difficult" items, a small effect due to the altered order of administration was apparent. Higher scores were obtained on the difficult items when they were preceded by a graded set of easier items, and the easier items were passed more often if they were preceded by the more difficult items. This trend seems more than a direct practice or homoactive suggestibility effect (Hull, 1933), as it is apparent in the hard-to-easy order as well as in the easy-to-hard order. Unfortunately, it was necessary to precede the two item-pools, in both orders, by two items which were intermediate in difficulty to the easy and difficult item-pools. Thus, in the easy-to-difficult order of administration the easier items were

191 ORDER EFFECT DURING HYPNOSIS

actually preceded by two harder items, but in the difficult-to-easy order, the difficult items were preceded by relatively easier items. Consequently, the mild effect produced by order of item difficulty in either order of administration was being somewhat counterbalanced by the opposite effect due to the two items which formed part of the induction.

Subjects tested in the difficult-to-easy order of item administration were more amnesic than Ss tested in the reverse order. This result is difficult to interpret because of the absence of significant differences with other items. When easy items, passed by most Ss, are administered at the termination of a hypnosis period, it is possible that S is more deeply hypnotized during the events immediately preceding the amnesia test. Alternatively, the amnesia may involve repression: S may be more affected by failure when the difficult, failed items are presented before he has experienced success with easier items. Hilgard and Hommel (1961) report evidence of this kind of selective repression when recalling failed items during hypnosis, although they noted that the possibility of enhanced recall following success could not be ignored. In fact, one can question whether the degree of amnesia is really different between the groups. When amnesia is lifted, it would be anticipated that the amount of additional material recalled would be related to the degree of amnesia. However, the amount recalled after amnesia was lifted was the same in both groups. Other alternative explanations of this result include a possible lack of retention, or perhaps a loss of interest in the procedure during the early failures.

The chi-square values on the remaining items were insignificant, though the values for Fly Hallucination and Posthypnotic Suggestion are higher than the remaining items. These two items, together with Amnesia, are more closely related to the subjective alterations assumed to accompany deep hypnosis than are the remaining direct and challenged suggestibility items. Recent evidence has shown that these items involve different components than the motor suggestions (Evans, 1963; Hammer, Evans, & Bartlett, 1963; Hilgard, et al., 1963), and may imply that success and failure may influence performance on only certain kinds of items.

The implications of this study are equivocal. Only relatively inconsequential effects were produced by the order in which easy and difficult items are administered. It is unclear whether this raises doubts about the validity of the clinical belief that success leads to success and failure predisposes to failure during hypnosis, or whether the present experimental design is inadequate to test this hypothesis. Certainly, item order seems to have little effect on total scores on a standardized psychometric device adequate to measure susceptibility

192 FIELD, EVANS AND ORNE

to hypnosis. On the other hand similar conclusions about clinical applications of hypnosis may be unjustified. Further research should take into account S’s perception of success and failure and should also eliminate procedures designed to minimize the importance of failing a specific item.

References

CORN-BECKER, FRANCES, WELCH, L., & FISICHELLI, V. Conditioning factors underlying hypnosis. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1949, 44, 212-222.

ERICKSON, M. H. Deep hypnosis and its induction. In L. M. LeCron (Ed.), Experimental hypnosis. New York: Macmillan, 1952. Pp. 70-112.

EVANS, F. J. Is there a general factor of hypnotizability? Paper read at East. Psychol. Ass., Philadelphia, April, 1963.

FURNEAUX, W. D. The heat illusion test and the structure of suggestibility. Int. J. clin. exp. Hypnosis, 1964, 12, 169-180.

HAMMER, A. G., EVANS, F. J., & BARTLETT, MARY. Factors in hypnosis and suggestion. J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1963, 67, 15-23.

HILGARD, E. R., & HOMMEL, L. S. Selective amnesia for events within hypnosis in relation to amnesia. J. Pers., 1961, 29, 205-216.

HILGARD, E. R., LAUER, LILLIAN W., & MORGAN, ARLENE H. Manual for Stanford Profile Scales of Hypnotic Susceptibility: Forms I and II. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1963.

HULL, C. L. Hypnosis and suggestibility: An experimental approach. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1933.

MEARES, A. A system of medical hypnosis. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1960.

ORNE, M. T. The potential uses of hypnosis in interrogation. In A. D. Biderman & H. Zimmer (Eds.), The manipulation of human behavior. New York: Wiley, 1961. Pp. 169-216.

SHOR, R. E., & ORNE, EMILY C. Norms on the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Form A. Int. J. clin. exp. Hypnosis, 1963, 11, 39-47.

SHOR, R. E., & ORNE, EMILY C. The Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Form A: An adaptation for group administration with self-report scoring of the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form A. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press, in press.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M. Hypnotism: An objective study in suggestibility. New York: Wiley, 1953.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & HILGARD, E. R. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale Forms A and B. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1959.

WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., & HILGARD, E. R. Stanford Profile Scales of Hypnotic Susceptibility: Forms I and II. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologist Press, 1963.

WELCH, L. A behavioristic explanation of the mechanism of suggestion and hypnosis.

J. abnorm. soc. Psychol., 1947, 42, 359-364.

The preceding paper is a reproduction of the following article (Field, P. B., Evans, F. J., & Orne, M. T. Order of difficulty of suggestions during hypnosis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 1965, 13, 183-192.). It is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Editor-in-Chief of The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis.