The Work of Hope

Sowing the Seeds of Grace in a Crumbling Town

C H A I N S A W ! ! ! Brrrrrip!!!” Ed Grove wrote, Tom-Wolfe

style, C H A I N S A W ! ! ! Brrrrrip!!!” Ed Grove wrote, Tom-Wolfe

style,

in an e-mail to his son. “Are you nuts? For graduation?

Sheese! What will be your next project?” The parents

of Matt Grove, CGS’03, had good reason to

worry when their son asked them to bring along a chainsaw when

they came down from Utica, NY, to see him graduate last May.

Grove had been arrested not long before in a protest of the

war in Iraq. At the end of senior year in high school, he deferred

admission to Penn after arranging with the bishop of Zimbabwe

to work for a year in an African hospital that was 30 miles

from the nearest paved road. He changed IVs, dispensed meds,

bandaged wounds, pulled teeth, and removed stitches and casts.

He used a manual put out by

the World Health Organization to figure out the settings for

the x-ray machine. “He did

everything but major surgery,” according to his mom,

Carole, who remembers vividly the worry of sending off her

18 year-old boy to a country 8,000 miles from home and under

siege by a fierce plague of AIDs. “The chainsaw incident

is minor—really minor!—in comparison.

I gave up any attempt at judgment or control or anything else

since Zimbabwe.”

On

the morning after graduation, Ed and Carole drove across the

Ben Franklin Bridge to a fixed-up row house in a rundown,

boarded-up North Camden neighborhood where Grove had a job.

He and his dad took the chainsaw from the trunk and—Brrrrrip!!—cut

two stumps from the dirt in front of a three-story, brick home

to make way for a flowerbed. Then they pulled out a masonry

drill, bored holes in the brickwork near the front door, and

bolted to the wall a honey-colored wooden plaque onto which

Grove’s fiancée

had burned the word Hopeworks. (Grove and Annie Wadsworth,

C’03, were married in September. They met in the office

of President Rodin, CW’66, during a nine-day sit-in by

the activist group Students Against Sweatshops.)

Hopeworks (http://www.

hopeworks.org/) is a faith-based, technology-training project

aimed at “empowering” at-risk youth in

Camden. It encourages young people to stay in school and out

of trouble by providing computer-skills training and work experience

in small-scale business ventures. The smell of baking bread

often fills the computer-crammed house. The warm aroma helps

feed the hunger of young trainees for a stable and caring home,

and the bread satisfies another more gnawing need.

“

To live in Camden is very difficult,” observes Fr. Jeff

Putthoff, Hopeworks’ director and a Jesuit priest who

resides in nearby Holy Name parish. “There are just lots

of situations that people live in that are full of pain. A

lot of it is just poverty. It’s a lack of resources—a

lack of medical care and education. It’s a lack of parents

who have jobs or housing that’s sure, instead of temporary.” A

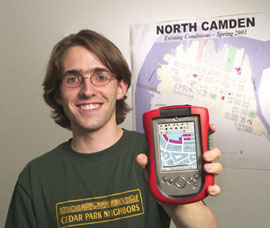

loose t-shirt and baggy pants hang shapelessly over Grove’s

stringy frame. Camden drug dealers often mistake him for a

suburban junkie wandering the neighborhood in search of a fix.

“

At ages 13 or 14,” he explains, “[Camden] young

people’s lives start to unravel, and they drop out of

school. . . . We use technology to engage the youth and get

them excited—helping them to see that there’s a

future they can take hold of.” As they progress through

the Hopeworks program, successful trainees start to lose the

hard edge of the street and become more confident of their

ability

to learn, which helps them discover more options. One

high school dropout went on to college to study computers and

ended up majoring in music.

Grove learned about Hopeworks as

an intern working next door at the North Camden Land Trust,

part of the requirement for his urban studies major. Hopeworks

had developed an online Web

design curriculum that was good enough to earn course credits

for trainees at a local community college. Fr. Putthoff had

been looking around for new areas of technology that Hopeworks

could grow into and thought Geographic Information Systems

(GIS) held promise for skill building and business opportunities

that might yield more jobs. GIS is software for visualizing

information, particularly data related to location. Grove learned about Hopeworks as

an intern working next door at the North Camden Land Trust,

part of the requirement for his urban studies major. Hopeworks

had developed an online Web

design curriculum that was good enough to earn course credits

for trainees at a local community college. Fr. Putthoff had

been looking around for new areas of technology that Hopeworks

could grow into and thought Geographic Information Systems

(GIS) held promise for skill building and business opportunities

that might yield more jobs. GIS is software for visualizing

information, particularly data related to location.

“

The only problem,” Fr. Putthoff mused to a companion

during one of many brown-bag lunches they had come to share

with Grove, “is who could lead such a project?”

Turning

to Grove, who was a junior and had some experience with GIS

at Penn’s Cartographic Modeling Lab, the priest

asked, “Do you think it’s a good idea?

Do you know anyone who’s graduated that could start this

out?” Grove responded, “My only question is, How

am I going to tell my parents that I’m dropping out of

college to do this?”

Grove turned out not to be another Camden casualty;

he simply put off graduation for a year. He transferred to

the College

of General Studies and became a part-time student, stretching

senior year over two years in order to work full time at Hopeworks.

Starting from scratch, he wrote training lessons one day at

a time. Eventually, he augmented Hopeworks’ budding GIS

curriculum by tapping into the University of Montana’s

online classes—at discounted tuition rates. Jack Dangermond,

president of ESRI, a leading producer of GIS programs, became

so enamored of Hopeworks’ mission and Grove’s moxie

that he donated the company’s expensive software. Last

summer, ESRI brought Grove and his trainees to its international

conference in San Diego to give a presentation on the 33,000-parcel

GIS map of Camden—the city’s first and only digital

map—that they had pulled together from old tax documents.

“

We trained the youth and created it in about five months,” Grove

says. “At

first, people didn’t think we were the real deal. . .

. We made [the Camden GIS map] to establish our legitimacy,

in the hope that it would get people interested in taking advantage

of our services.” Hopeworks now fields nearly a half-dozen

word-of-mouth referrals a week, from small nonprofits to big

city governments. Some projects require months of work, while

youths go into neighborhoods with hand-held computers to collect

information. Smaller jobs need only downloading

and crunching of existing data. Clients include the Camden

Housing Authority, Camden County Improvement Authority, New

Jersey Tree Foundation,

Rutgers University, and other community groups looking for

affordable GIS services. “If anyone wants to do any kind

of parcel-level analysis in Camden,” Grove brags, “they

have to come to Hopeworks.”

Around Thanksgiving, Grove left Camden

and returned to Utica to take over the family business, the

Bagel Grove, where he

had worked growing up. “Hopeworks has engaged a lot of

his idealism,” Fr. Putthoff says, “and it might

have roughed up some of that idealism too.” In the bagel

shop, Grove and his wife plan to incorporate some social-awareness

events and perhaps

experiment with employee ownership, but they also are determined

to keep the business in the black. It’s all a matter

of pushing reality as far as you can—until it pushes

back.

Camden’s “youth crisis,” he learned,

is too big for one person—or one organization. Sometimes,

in the precarious lives of the youths he has worked with, illness,

crime, job loss, and any number of misfortunes can force someone

to drop out of school and find any McJob that will keep the

family afloat. “That’s an example of the reality

overwhelming all the good you can do,” he says. “I’m

not going to be the savior of all these people. Hopeworks isn’t

going

to be the savior.”

Back in Camden, the weeds that once

caught trash in front of Hopeworks are gone, and there are flowers

blooming in the bed

Grove and his parents helped prepare with their chainsaw. A sweet

gum grows there too, a seedling from Elvis Presley’s Graceland

mansion, which one of the trainees won at a GIS conference in

Texas last summer. Hope—and a little

grace. “It’s humbling,” says Grove. “I

guess you just have to trust that there will be other people

in the lives of these youths who will help them with the different

problems and situations that come up.”

|