Penn Provost and Neuroscientist Does Clockwork

Folklore has it that the Nuremberg locksmith Peter Henlein built one of

the world’s first pocket watches in the early 1500s. The invention

of spring-driven clocks, about 100 years before that, was a decisive advance

toward making timepieces small and pocketable.

The Tick

Doc

With an internal "prime mover," clocks

became portable, as long as watchmakers were expert enough to cut the

delicate springs and fine-toothed wheels that made them run. It makes

sense that some of these new artisans should have come from the ranks

of locksmiths. What is surprising is that a modern-day maker of

mechanical clocks—an art and an industry that died abruptly with

the invention of the quartz watch—should come from the ranks of academic

administrators.

"I’d

like to give you a feeling for the intrinsic beauty of these objects,"

provost Bob Barchi, Gr’72, M’73, announced to a group that had

gathered to hear him discuss the aesthetics

and engineering of antique pocket watches. The presentation was one of

this year’s explorations of time, hosted by the Penn Humanities Forum.

"I’d

like to give you a feeling for the intrinsic beauty of these objects,"

provost Bob Barchi, Gr’72, M’73, announced to a group that had

gathered to hear him discuss the aesthetics

and engineering of antique pocket watches. The presentation was one of

this year’s explorations of time, hosted by the Penn Humanities Forum.

Although the provost talked a little about ornamentation, his own aesthetic sensibility runs more to the mechanical ingenuity that, in 400 years, turned crude, unreliable wheelworks into precision timekeepers. "It’s like looking at a beautiful painting," he observed of all the interlocking movements, "but the beauty is wrapped up in what they do."

Barchi is a collector of old pocket watches, mostly 18th century English pieces. He doesn’t collect older ones simply because they’re too rich for a university professor’s wallet. Twenty years ago, he repaired and restored old timepieces in his fully equipped basement machine shop for dealers on Pine Street, Philadelphia’s Antique Row. "It allowed me to support my habit," he admits, "and gave me an opportunity to handle clocks and watches I couldn’t afford."

Besides

being Penn’s chief academic officer, Barchi is a physician, a neuroscientist,

and a professor of neurology and neuroscience in the medical school. In

part, his research attempts to unlock how electrical signals are generated

in the brain, the prime mover of all human thought and activity. "It’s

the most complicated of all machines," he states. "The way the

brain works, the way the parts interact in this intricately functioning

device, also can make you so pleased that you laugh when you discover

some new thing—something that’s so neat that it works that way."

Neat is a prime category in the Barchi aesthetic.

Besides

being Penn’s chief academic officer, Barchi is a physician, a neuroscientist,

and a professor of neurology and neuroscience in the medical school. In

part, his research attempts to unlock how electrical signals are generated

in the brain, the prime mover of all human thought and activity. "It’s

the most complicated of all machines," he states. "The way the

brain works, the way the parts interact in this intricately functioning

device, also can make you so pleased that you laugh when you discover

some new thing—something that’s so neat that it works that way."

Neat is a prime category in the Barchi aesthetic.

Barchi, though, is not a true collector. In some cases, he’s kept movements—the guts and gears of a clock—that no longer have the case, the hands, or even the dial, which renders them worthless to a collector. "I’m more interested in the pleasure they give me as a piece of machinery," he says. "I just love to take out and look at and take apart and tinker with and put back together—just to feel how it works."

When he was five, he gutted his mother’s "best watch" but was unable to resuscitate it. "It caused more than a little trouble," he recalls. His grandfather had an eighth-grade education but still founded a machine shop that earned several patents, and Barchi’s father, who was an engineer, was also a patent holder. "I grew up with people who invented machines," he says. "An appreciation for the beauty of solving problems with mechanical approaches is something that’s definitely hardwired into my brain."

What Makes

it Tick?

Today, he can not only take apart and reassemble

a clock with ease, he also designs and builds them from scratch. From

scratch means not just putting together the wheels and shafts and

springs, but machining sheets of brass on the lathes, mills, and drill

presses in his basement workshop to shape each hand-fitted piece for the

movement.

"It’s really a very simple device," he explained to the group that came to hear him talk about watches. "You take a series of gears and connect them to some driving force that’s constant, say, a weight…. You then have a multiplying device, where one turn of this [big] wheel, pulled by the weight, might make that [little] wheel turn, say, 12 times. So two rotations of the big wheel makes 24 rotations of the little one. And if you put the right numbers on it, you have a clock.

"Or do you?" he queries. "What you need to make this device into a clock is something that slows down the escapement of that wheel," otherwise the hands will spin around the dial for a minute or so until the weights hit the floor.

The clock escapement is one of history’s most clever inventions, and its impact has been far reaching. The mechanism governs the ticktock, catch and release of one tooth at a time. It measures out, in discrete stop-and-go units, the force exerted by the trailing weights or the mainspring.

The

first watches had only an hour hand and would typically lose or gain an

hour or more a day. As escapements grew more refined, precision timekeepers

became dependable enough to coordinate the trains that hurtled in opposite

directions along the same tracks of the American railroad. In Walden,

Thoreau reported that the trains "go and come with such regularity

and precision…that the farmers set their clocks by them, and thus

one well conducted institution regulates a whole country."

The

first watches had only an hour hand and would typically lose or gain an

hour or more a day. As escapements grew more refined, precision timekeepers

became dependable enough to coordinate the trains that hurtled in opposite

directions along the same tracks of the American railroad. In Walden,

Thoreau reported that the trains "go and come with such regularity

and precision…that the farmers set their clocks by them, and thus

one well conducted institution regulates a whole country."

Often, it’s the mechanical cunning of a unique escapement that captivates Barchi and inspires him to hold on to an antique watch or to design a new clock. "I see a particular clock," he says, "or a particular escapement and think: ‘That’s really pretty neat.’"

Time to

Play

As you enter the front door of his home,

your eye, if not your ear, immediately catches the floor-standing regulator

ticking away. To the uninitiated, it’s a grandfather clock, but the

clockmaker is quick to point out the superior

design and performance that earn the timekeeper the honorific "regulator."

"It keeps incredibly accurate time," he boasts. The precision

instrument has a brass-cylinder pendulum, and it’s matted-nickel

dial is etched in blackened script with Barchi’s name.

He’s also built a Congreve clock, which is powered by a steel ball that rolls along a groove cut into a tiltable table. It takes the ball 30 seconds to run the course, when it trips a release that moves the clock ahead a half minute and tilts the table back in the other direction, which starts the ball rolling once more down the zigzag groove toward a trigger at the other end.

Each Barchi clock represents thousands of hours at the draftsman’s table and in the machine shop. "I work on them when I have the time," he says. "They may take me years to finish because they’ll be interrupted by the birth of a child or new professional responsibilities that don’t give me a lot of time to play."

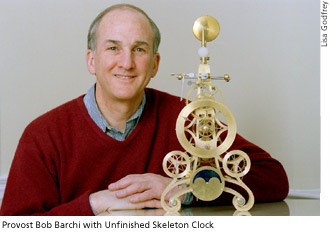

Currently, he’s winding down on an elaborate skeleton clock that will tell the time, the day of the week, the month, and the lunar phase. The timepiece displays its mechanical innards, hung on a graceful brass frame. The most prominent element is a grasshopper escapement, so named for the angled rod that resembles the insect’s bent back leg. Barchi notes that there remain a few hundred hours of work before the skeleton clock is finished, but it’s hard to say how many years that is in provost time.

"I’ve got a couple more clocks sitting in my mind," he says. "One of them’s got an interesting escapement." The other tells the time on numbered bands that are mechanically rotated. "It’s an early version of a digital clock," he explains.

It’s a funny notion: the mechanical and the digital. It conflates the medieval with the modern. Barchi’s timepiece tinkering links the technology of a vanished past with a present sensibility, perhaps unlocking new ways to make mechanical forces, motions, and ratios tick out the time—just because it’s neat.

"My kids will have these clocks when I’m dead," he says, gazing now into the future. "These clocks will be running long after my grandkids are gone."