Rescue at 13,000 Feet

How Hillary Rodham Clinton Saved the Dissertation of a Penn

Archaeologist

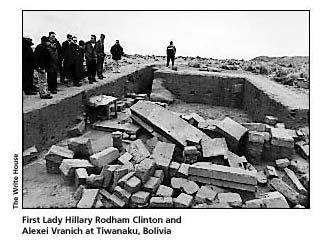

Alexei Vranich was having a really bad day. It was only three weeks until the end of his excavation project at Tiwanaku, Bolivia, and the Department of Culture had, once again, suspended all work. Trenches lay open, filled with artifacts and architecture waiting to be logged, and the rains were coming. The losses could be dramatic. The rain wreaks havoc on anything that is exposed. In this case it would also wash away a substantial portion of Alexei's Ph.D. dissertation and many years of hard work. Then, the other shoe dropped: could he, since he was presently unoccupied, lead a group of visiting conventioneers on a tour of Tiwanaku?

The conference in question was the First Ladies of the Americas which had been meeting for three days in La Paz, two hours away. Alexei envisioned a group of conventioneers trailed by such a large cadre of staff and officials that they would have little time to explore the site. His initial impulse was to refuse, but he realized that meant the group would be left to a tour bus and a local guide who would, undoubtedly, tell them that Tiwanaku had been built by the Egyptians - a perspective put forth in a recent TV special with Charleton Heston. Besides, his political antennae quivered as he remembered: the department that closes down sites can also open them. He agreed to lead the tour.

Several days later Alexei dutifully went to meet his visitors. Instead of conventioneers and a contingent of staff and officials, however, he was met by White House staff members who whisked him away to conduct an in-depth tour, without the press, for a single first lady: Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Ironically, it was a problem with site access that first brought Alexei

to Tiwanaku. He went to Bolivia to join Penn's Associate Professor of

Anthropology Clark Erikson on a project to reconstruct ancient Andean

agricultural terraces. When that project was delayed, Alexei took an

interim assignment as a surveyor on a plan to determine the boundaries

of a national park. The director of the terracing project, Leocadio

Ticlla of the National Institute of Archaeology of Bolivia, was also

working at Tiwanaku on the Temple of Puma Punku. Alexei joined the crew

as a volunteer and impressed the other archaeologists there. Thus, when

the terracing project fell through altogether, Alexei asked if it would

be possible to work on Puma Punku for his dissertation. Ticlla, whom

Alexei describes as "one of the truly noble men in the business," took

on the daunting bureaucracies of archaeology and the state and prevailed

in both cases. And so, after months of waiting, Alexei found himself

working at one of the most coveted archaeological sites in South

America.

Tiwanaku is the most important excavation in Bolivia and, until recently, had been closed to all digging for 50 years to stop constant looting. The city is pre-Incan and existed from 600 to 1100 AD. It had already been abandoned by the time the Inca arrived, but continued to be important, especially as a ceremonial place. According to legend, when the conquering Inca leader arrived, he asked his artisans and stonemasons to study Tiwanaku and then rebuild Cuzco in its image. The beauty of the stonework still brings artisans to the site.

Mrs. Clinton knew about Tiwanaku, and intended to have a good look. Mysteriously, the press received misinformation about her destination that day and ended up waiting for her on the banks of Lake Titicaca, some ten miles away. Thus, after the initial flurry of activity where the Secret Service and the Bolivian army thoroughly checked out the area and bystanders (an old woman and her herd of cows), Alexei found himself face-to-face with the first lady, discussing archaeology as he would with a colleague.

After introductions, the White House staff dropped back and followed the two at a discreet distance. The weather was cold and rainy, but that didn't dim Mrs. Clinton's enthusiasm. Alexei was impressed by her "intelligence and insight." The first lady was particularly interested in the interstices of the Spanish and Andean cultures and the implications for South America, so Alexei took her to the Tiwanakuan village church that had been built during the Spanish rule. It was the Catholic church, built by natives with stone blocks looted from the temple. The saint's day the villagers chose to honor conveniently coincided with a traditional village celebration and, over the centuries, the two rituals had become uniquely entwined.

Mrs. Clinton was charmed by Alexei's tale of his participation in a day-long festival filled with dancing and ceremonial drinking of alcohol and fruit juice. Late in the day's festivities, he found himself in the church dressed as a bear and sitting in a pew with other bears, a situation which only he thought the least bit odd.

Alexei also explained that since he had not planned to work in Tiwanaku, he arrived without the funding that usually supports American students on digs in foreign lands. Being an entrepreneurial Penn type, however, he pooled his room and board money, got donations from friends and family, and set up shop. His crew, Aymara villagers from Tiwanaku who had worked the site for many years, were somewhat set in their ways. Measurements at Bolivian archaeological sites had always been made with a small string attached to a stake and so, when Alexei pulled out his $10,000 laser theotolite (capable of making measurements to .001 of a centimeter and borrowed from Penn's anthropology department), a discussion on procedure ensued that went all the way to Bolivia's Department of Culture. The issue was finally resolved with the crew using the stake and string and Alexei using the theotolite.

Despite this initial disagreement, Alexei found the Bolivians to be wonderful people. They speak both Aymara and Spanish and, as Spanish is Alexei's first language, he was soon able to communicate and learn the culture. Life was relatively simple - up in the morning and then out to the site; dig with the crew until dusk, and write up the results in the evening. Since there was no running water in his house and the temperature at 13,000 feet can get quite nippy, Alexei went to the capital every weekend for the luxurious indulgence of a hot shower. He acquired a tan, thanks to the altitude, and lost 15 pounds because there never quite enough to eat.

After their visit to the church, Mrs. Clinton and Alexei went to the temple of Puma Punku, a spot rarely visited by tourists because of its out-of-the-way location. As they walked, the first lady expressed her belief that archaeology is increasingly important to a people's search for identity - especially in countries where there is no tradition of written language. Her insight was particularly relevant to Bolivian history, for example, where the only written record was of the colonial period that began in the 1500. Today, a rich legacy from the previous 8,000 to 10,000 years is emerging with the artifacts and architecture of these pre-colonial sites. Archaeologists now have the technology not only to reconstruct the buildings and cities at these sites but, to some degree, the daily lives of the inhabitants. The written reports of these excavations have the power to restore to a proud people at least a part of their civilization.

As the party explored the temple, Alexei pointed to an artifact that proved conclusively that all governments, whether ancient Bolivian or contemporary U.S., have basic similarities. He showed the visitors a small copper clamp that had been installed to link two of the multi-ton blocks of stone. "If these blocks decided to move, this tiny bit of metal would hardly have stopped them. This," he added, "is a prime example of pre-Columbian government waste." Later, as they walked back to their cars, Mrs. Clinton asked how the dig was proceeding and, when Alexei told her his troubles with the senate, she smiled and admitted, with a twinkle in her eye, to having some similar experiences in that area.

After the group left, Alexei quickly informed the minister of culture about the tour and emphasized that he had no advance knowledge it would include the first lady of the United States. He stressed what wonderful news it was for Tiwanaku, however, because she loved her visit and wanted Alexei to keep her informed about progress. Mrs. Clinton had asked for his address, he added, and made him promise to keep in touch. The next day, without a hearing, without any official papers, the site magically reopened (a move Alexei is sure was solely in response to Mrs. Clinton's interest rather than any intervention on the part of the U.S.). He finished up before the rains and came back to Penn. In January, he went to Washington, D.C. for the inauguration.

During the next year he will write his dissertation. After that Alexei

intends to pursue a post-doc. Eventually, the combination of Penn's

reputation, the post-doc, and his experience at the hottest site in

South America should make him an attractive candidate for an academic

position. And then? Well, he'll teach in the fall and spring and, with

luck, pack up with a bunch of students and head back to the altiplano

and Bolivia, and start digging all over again.