Cost-benefit analysis can increase trust in decision

makers

Jonathan Baron1

University of Pennsylvania, Andrea D.

Gurmankin

Rutgers University

Abstract

Four experiments on the World Wide Web asked whether people

trust an agent (a company or government agency) more when the

agent uses cost-benefit analysis (CBA) or, more generally,

bases decisions on their consequences. Experiment 1 used a

scenario concerning the installation of a safety device in a

car. The decision was made either by a company or a government

regulatory agency. Trust in the agent increased when the

decision made was consistent with the results of CBA. Part of

the CBA involved comparison with other safety devices that were

either installed or not. Such comparison increased trust even

when the subject disagreed with the agent's decision.

Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 with a health-care

scenario involving decisions by insurance companies about

whether to cover a treatment. Experiment 3 showed that trust

could be increased by CBA even in highly charged moral

contexts. Experiment 4 found that people are willing to take

cost into account more for social decisions than for individual

ones. The results together suggest that people might be

responsive to clear justifications of policies that emphasize

costs, benefits, and alternatives, even if these policies

violate their intuitions.

Introduction

Government regulatory agencies, courts, health insurers, and

other institutions sometimes try to adopt policies that bring

about the best overall outcomes, all things considered. In

trying to do this, they often use cost-benefit analysis (CBA) or

some other form of formal analysis based on the costs and

benefits of expected consequences. They may measure the

consequences in terms of money, life years, or utility. When

agencies (in this general sense) attempt to use CBA (likewise in

a general sense, including other forms of decision analysis),

they often face opposition, because people's intuitions are often

inconsistent with the results of CBA. If agencies are to succeed

in their efforts to improve outcomes, then people must trust the

agencies even when their policies are counter-intuitive. Can

people come to trust agencies that make decisions consistent with

CBA, despite the conflict with their intuition?

Breyer (1993) argues that regulation of risk is hampered by a

cycle in which the public reacts to some incident, such as Love

Canal (Kuran & Sunstein, 1999), the government passes some

poorly crafted legislation in response to public reaction, such

as the Superfund laws, and the legislation itself provokes a

counter-reaction, and the cycle continues. If the agencies were

trusted more, Breyer argues, the legislature would give them

broader scope, and they could regulate in the public interest.

In order to be trusted more, they must earn that trust: "Trust

in institutions arises not simply as a result of openness in

government, responses to local interest groups, or priorities

emphasized in the press - though these attitudes and actions

play an important role - but also from those institutions'

doing a difficult job well" (p. 81).

Breyer's solution is to develop, over time, a branch of the

bureaucracy that is in fact competent and expert in making

decisions according to their consequences and is also perceived

as being competent and expert. Bureaucrats in such a branch must

be competitively selected, well trained, and insulated from

outside pressure. Although Breyer does not mention it, the

current U.S. Federal Reserve may be a case in point (at least

until the next economic disaster). The control of interest rates

in the U.S. used to be heavily politicized, but now most citizens

(and legislators) seem to trust the Federal Reserve to try to

control interest rates in the public interest.

However, good decisions, that is, those that are in the public

interest, may not always be perceived as good decisions. Public

perceptions of risk seem to be influenced by intuitive judgments

that disagree with those that experts might make according to

CBA. Such intuitive judgments are often based on principles

other than those designed to bring about the best consequences.

Risk experts, of the sort that might serve in a Breyer-type

regulatory branch, are likely to be trained in welfare economics,

decision theory, and cost-effectiveness analysis. These

disciplines are based on theories about how to achieve the best

consequences (or why the best consequences are not achieved). In

the case of risk regulation, the best consequences amount to

minimizing harm for a fixed cost, or minimizing cost for a given

level of harm, or minimizing some weighted sum of cost and harm.

"Harm" may amount to something as simple as lost years of life

(or lost quality-adjusted years).

Currently, regulatory agencies, courts, and health-care providers

rarely rely on CBA. Thus, from the perspective of CBA, we could

do more good with less money than we are now doing. (See, for

example: Slovic, 1998; Tengs et al., 1995.) Psychological

research suggests that inefficient decisions of these agencies

are based to some extent on the nature of human judgments. On a

number of issues, people's intuitive judgments are biased

systematically away from the recommendations of CBA (Baron, 1998,

2000), such as the preference for harms of omission over harms of

commission. When acted on, such biases (away from maximization

of consequences) can cause worse outcomes. If we are concerned

with improving outcomes, then we might want to examine the role

of these effects in decision making.

As a result of such judgments, agencies are often put in a

conflict between the intuitions of their clients and the advice

of technical experts, who usually base their recommendations on

an analysis of consequences. This applies to such agencies as

the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Environmental

Protection Administration (EPA). For example, EPA has recently

been taking into account the distribution of risk as well as its

total amount, thus siding with popular intuition. FDA may have

done the same in its recent decision to withdraw the rotavirus

vaccine. At an individual level, doctors who recommend DPT

vaccine are often caught in the same bind.

One way an agency might deal with such intuitions or biases is to

attempt to explain its actions, especially when they are

consistent with CBA but inconsistent with public opinion. Can

this help? The experiments reported here attempt to simulate the

effects of various types of CBA on trust.

Experiment 1

Viscusi (2000) asked juror-eligible citizens in the U.S. whether

they would assess punitive damages against a car company that

decided not to make safety improvements in a car's electrical

system, leading to deaths from burns, and, if they would assess

punitive damages, how much. When the company had carried out a

CBA to make the decision about making the safety improvements,

the proportion of subjects who assessed punitive damages was no

lower than when the company did not carry out the CBA (even

slightly higher). The analysis assigned a value to human life,

and raising this value up to $4,000,000 per life had no effect.

In fact, subjects assessed higher punitive damage awards when the

value of life was higher, apparently because they anchored on the

number given.

Viscusi's result is discouraging for the proponents of the use of

CBA by corporations and government. It suggests that when a

company uses such an analysis is used to justify inaction in a

case like this, it will make people no more forgiving of the

company.

Viscusi gave the scenarios with and without analysis to different

subjects. Such a between-subject design lacks statistical power,

and it may have missed detecting an effect even with several

hundred subjects. Of course, it did detect the anchoring effect

with the value of life, but that effect involved a numerical

response, and the main analysis was simply whether or not

punitive damages were assessed. The experiment may have been

insensitive because the probability of awarding some damages was

on the order or 90% overall, leaving little room for effects of

experimental manipulations.

Experiment 1 used a more sensitive design to assess responses to

CBA in the same context. It manipulated several variables

concerning the type of analysis done, and whether the final

decision is consistent with the analysis. It asked about trust

in the agency or company that did (or did not do) the CBA, and

about fines in case of injury. The fines serve as a second, more

concrete, measure of the extent to which the agency is at fault.

The general result is that, when the decision is consistent with

the analysis, CBA increases trust and reduces fines assigned for

mishaps, regardless of whether the decision suggested by CBA is

consistent with the subject's judgment.

Method

Ninety-five subjects completed a questionnaire on the World Wide

Web. Their ages ranged from 18 to 74 (median 34); 26% were

male; 9% were students. The questionnaire began:

Safety features

This questionnaire concerns the trade-off between money and

safety. Governments and corporations are faced with choices, in

which they can spend more money and reduce risk.

The safety issues concern prevention of injuries and death.

We shall give the number of "serious injuries" in each case. All

serious injuries require hospitalization. Half of these injuries

result in some permanent disability, and 10% result in death.

The cost of prevention is paid by consumers. For example, if

a safety device is put in a car, the price of the car increases

by the cost of the device.

The questions ask what you would do in such cases, and also

how much you would trust government agencies or corporations that

made various choices.

Some items ask you to compare two government agencies,

concerned with safety regulation. Imagine that either of these

agencies could make a regulation about the device in question.

Also, imagine that these agencies could be sued in court, just as

corporations can be sued.

We are interested in what reasons you think are relevant to

these decisions, so please pay attention to the different

reasons.

Each screen involved a comparison of two agents (corporations or

agencies). The first agent always based the decision on cost

alone. The second agent based the decision on benefit as well as

cost (although the decision was the same). On half of the cases,

the second agent also compared the device in question to other

devices. The wording read, with alternatives and noted in

brackets:

Consider a safety device for cars. Its cost is $50

per car, and it would increase the car's price by $50. Its

benefit is that it would prevent 50 [5]

serious injuries, for 200,000 drivers. It would reduce each

driver's chance of injury by .025 [.0025] % over the lifetime

of the car.

Other safety features not [now] installed in cars

could prevent injuries at a lower [higher] cost per

injury prevented.

Should the government require [Should a company install] the

device?

Agency [or Company, throughout] A decided [not] to require that

the device be installed [install the device]. Agency A knew the

cost of the device, but it did not try to discover the benefit

of the device (the number of serious injuries prevented, which

you were told above). Agency A based its decision on cost

alone.

Agency B also decided [not] to require that the device be

installed [install the device]. Agency B did discover the

benefit (the number of serious injuries prevented) as well as

the cost. Agency B based its decision on the average cost of

preventing each serious injury.

Agency B did not attempt to compare the costs and benefits of

this device to other safety features already installed in cars

that prevent injuries at a higher or lower cost per injury

prevented.

[For half of the cases, the last two sentences were:] Agency B

also determined that other safety features [not] installed in

cars can prevent injuries at a higher [lower] cost per

injury prevented.

Which agency would you trust more to make decisions like this

in the future?

[If the device was not installed, the following was asked:]

Suppose both agencies were sued in court because they did not

require that the device be installed. Injuries occurred that the

device would have prevented. The law says that the maximum

payment to victims is $1,000,000 per injury. How much should

each Agency pay each victim (in thousands of dollars, digits only)?

Agency A $ Agency B $

The 32 screens were presented in a different random order for

each subject. Each screen described two agents (decision

makers). The 32 screens represented all possible combinations of

two levels of each of five variables:

- Government agency vs. private company as the agent

(manipulated mainly to increase the number of cases per subject);

- Benefit of the safety device (5 vs. 50 serious injuries);

- Whether the device was to be installed or not (the same for

both agencies);

- Whether the device had a higher cost-effectiveness than other

devices now installed vs. a lower cost-effectiveness than

other devices not installed (betterness);

- Whether the second agent had determined #4 or not

(knowledge).

Note that #4 implied either that the device was probably worth

installing, since it was more cost-effective than other devices

installed, or that it was not worth installing, because it would

be more cost-effective to install some other device. Thus, this

manipulation put the decision in a larger context, as a more

thorough CBA would do.

Results

Because the design was within-subject, all analyses are based on

t tests of contrasts or interactions (differences of differences).

Whether the device should be installed

Consider first the question about whether the device should be

installed (Should-install). On the average, subjects favored the

installation of the device, with a mean score of 0.31 (which

differs from 0; t94=5.11, p=.0000) on a scale where 0 is

neutrality and each step on the answer scale is 1 unit (so that

"probably" is .50, and "certainly not" is -1.5).

Should-install was sensitive to the benefit (.45 with 50

injuries, .17 with 5; t=6.55, p=.0000), although 47% of the

subjects showed either no effect or a (small) reversed effect.

(Some of this 47% favored the device very strongly regardless of

the benefits.)

Should-install was also sensitive to the implications of

comparisons to devices installed or not installed (.58 when less

cost-effective devices installed, .05 when more cost-effective

devices not installed; t=6.92, p=.0000; 31% showing no

effect or a small reversal). Call this the effect of

"betterness."2

Trust

We ask two questions about trust. First, do people trust the

agent that considers both benefit and cost (B) more than the

agent that considers only cost (A)? This is the simplest

question about whether CBA increases trust. Second, is trust

affected by whether B act's consistently with the results of the

analysis?

On the first question, Table shows the means for

trust in the agent that did the more thorough analysis (B).

Agent B examined both benefits and cost while agent (A) examined

only cost. The two agents on each screen always made the same

decision. The fact that these numbers are positive indicates

that subjects were more inclined to trust the more thorough agent

(B); the mean rating was .68 on a scale where each step is 1 unit

and 0 is neutrality (t=13.03, p=.0000).3

Table 1: Trust in B, the more thorough agent (0 is neutrality).

| Not installed | Installed |

| No knowledge | Knowledge | No knowledge | Knowledge |

| 5 lives, worse | 0.43 | 0.85 | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| 50 lives, worse | 0.43 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.79 |

| 5 lives, better | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.62 | 1.03 |

| 50 lives, better | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 1.13 |

Turning to the second question, about consistent action, the size

of the benefit (number of lives saved) should affect the

desirability of installing the device and should thus interact

with whether the device is installed. B should be more trusted

when B is responsive to benefit. Although size of the benefit

did not have a significant main effect, higher benefit leads to

more trust when the device is installed than when it is not

installed (t=2.71, p=.0079).

Betterness - whether the device was better (in

cost-effectiveness) than installed devices vs. worse than

uninstalled ones - also had no main effect. Betterness should

increase trust when B knows about it and acts on it. Thus, it

should interact with knowledge and installation.

Knowledge - whether the agency knew about betterness -

increased trust (t=7.09, p=.0000). Knowledge did not

interact with installation, betterness, or benefit. However the

expected triple interaction between knowledge, betterness, and

installation was significant (t=5.66, p=.0000). Knowledge

led to the highest trust when the device was better than other

devices and when it was installed (lower right of Table

1). When the device was better and not installed,

knowledge did not affect trust significantly either way.

Importantly, though, knowledge led to increased trust when the

device was worse and was not installed (the upper left of the

table; t=7.62, p=.0000). In sum, the agency earned more

trust when they attended to comparative information and followed

its implications.

In sum, knowledge about betterness increase trust in decisions

that are consistent with that knowledge. Does this effect happen

even when the subject disagrees with the agency's decision? To

test this, we examined pairs of cases (screens) that differed

only in knowledge. We selected those pairs in which the subject

disagreed with the agency's decisions in both cases. (25 subjects

had no such pairs.) Knowledge led to greater trust even within

these pairs (mean effect of 0.34, t69=5.04, p=0.0000).

Fines

In cases where the agency or company described did not install

the device, we asked about fines (with a maximum of $1,000,000

per injury). The mean fine for agent A (no analysis of benefit)

was $504,000, and the mean for B was $440,000. The range of

fines was high, however. To get a better measure of the relative

fines for A and B, we computed the ratio 2A/(A+B)-1, which

would be 1 if the subject fined agent A and did not fine B, -1

if the subject fined B but not A, and 0 if the fines were equal.

(Fines of 0 for both were treated as missing data.) The mean of

this measure, 0.098, was positive (t93=5.00, p=.0000),

indicating that more analysis led to lower

fines.4

Table shows how this measure depended on

knowledge, benefit, and betterness. Recall that the measure is

higher when agent B, the one who does more analysis, is fined

less for not installing the device. It is thus parallel to the

measure of trust in B, when B does not install the device.

Table 2: Relative fine for A (no analysis) vs. B (1 if all for

A, -1 if all B).

| No knowledge | Knowledge |

| 5 lives, worse | 0.101 | 0.162 |

| 50 lives, worse | 0.066 | 0.173 |

| 5 lives, better | 0.071 | 0.069 |

| 50 lives, better | 0.099 | 0.048 |

The measure was higher (B fined less) when the uninstalled device

was worse compared to the alternatives (t = 3.71, p = 0.0004), when it had less benefit (t = 1.85, p = 0.0677),

and when B had knowledge of this (right column vs. left, t = 4.12, p = .0001).

Of greater interest is the interaction between knowledge and

betterness (t93=3.17, p=0.0021). The effect of betterness

(top two rows vs. bottom two rows in Table 2) was

greatest when B was informed about it.5 In sum, appropriate use

of CBA reduces fines. The results parallel those for the trust

measure.

Does the effect work with all subjects?

It is possible that - despite the main effect of increased

trust in those who use CBA - some subjects distrust CBA so much

that it reduces their trust. Clearly this did not happen with

most of our subjects, as the overall effect was to increase

trust. To examine individual differences, we carried out a

one-tailed t test for each subject in "trust in agent B." The

test was one tailed because we were looking only for subjects who

trusted B less than A. But, of course, with enough subjects,

some of these tests would be significant by chance alone. Thus,

we examined adjusted p-levels for multiple tests. We used the

step-down resampling procedure of Westfall and Young (1993) as

implemented by Dudoit and Ge (2003). By this test, 2 subjects

showed significantly greater trust in agent A at p < .05 (one

tailed - p=.0223 for both). Thus, CBA reduces trust for some

people, but not for very many in our population.

Experiment 2: Health insurance

Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 in the context of health

insurance.

Method

One hundred and two subjects completed a questionnaire on the

World Wide Web. Their ages ranged from 18 to 74 (median 35);

28% were male; 15% were students. The questionnaire began:

Health insurance

This questionnaire concerns the trade-off between money and

health. Health insurance companies must decide which treatments

to cover (pay for).

On each screen, you will see some information about a cure for

a serious disease. Suppose that all diseases are quite serious

and chronic, making for a low quality of life and usually a

shorter life too. Examples are diseases like severe arthritis,

senility, emphysema, and heart disease.

The treatments work with one type of each disease, so they are

given only to people with that type. Once the patient is

diagnosed as having that type of disease, the treatment is given

all in one dose of a drug. The drugs are expensive because of

the methods needed to produce them.

You will see:

- The number of people who have the type of disease and can get

the treatment.

- The percent of these that will be cured (100% or 50%).

- The cost per treatment.

- The increase in the insurance premium required to pay for

this coverage. The total cost of the treatment must be divided

up among 10,000,000 policy holders.

- The cost per cure (the same as the cost per

treatment when the cure rate is 100%).

- A comparison of the cost per cure with other treatments that

are currently covered or not covered.

You will also see information about two different insurance

companies and how they decided whether or not to cover the

treatment. We are interested in what reasons you think are

relevant to these decisions, so please pay attention to the

different reasons.

You will be asked

- Whether the treatment should be covered.

- Whether you would trust each insurance

company to make future decisions of this sort.

- Which company you trust more.

The wording of the items read [with alternatives in brackets]:

- This type of disease affects 1,000 [2,000] people per year.

- The treatment would cure 1000 of these people, or 100%

[50%] of them.

- The cost per treatment is $200,000 [$2,000,000].

- If this treatment is covered, the annual premium paid by

each of the 10,000,000 policy holders must increase by $20 [$40, $200, $400].

- Because the treatment cures 100% [50%]

of those who get it, the cost per cure is

$200,000 [$400,000, $2,000,000, $4,000,000].

- Other treatments not [currently] covered by Companies

A and B could cure more [less] serious diseases at a

lower [higher] cost per cure.

Should insurance companies cover the treatment?

Company A decided [not] to cover the treatment. Company A knew

the cost of the treatment for each policy, but it did not try

to discover the benefit of the treatment (the percent of cures,

which you were told above). Company A based its decision on

cost alone.

Company B also decided [not] to cover the treatment. Company B

did discover the benefit (the percent of cures) as well as the

cost.

Company B based its decision on the cost per cure. Company B

did not attempt to compare the costs and benefits of this

treatment to other treatments that it currently covered or did

not cover.

[Company B also determined that other treatments that it

did NOT cover currently [currently covered] could cure more

[less] serious diseases at a LOWER [HIGHER] cost per cure.]

On the basis of this information alone, how would

you feel about having insurance from Company A

On the basis of this information alone, how would

you feel about having insurance from Company B

Which company would you trust more to

make decisions like this in the future?

Each subject saw all combinations of the five variables in a

different random order. The variables were: Cost, Cure rate,

Coverage (whether A and B covered the treatment or not), Better

(whether the treatment was better than alternatives in terms of

cost and effectiveness, or worse in terms of both), Compare

(whether the company compared the option to alternatives). The

premium increase was derived from Cost and Cure rate.

Results

In general, subjects favor decisions that are consistent with a

CBA. The measure Should-cover, the subject's opinion about

whether coverage should be offered, was defined so that 0 was

neutrality and each step on the scale was one unit. The means of

Should-cover depended on Cure (.65 for 100%, .11 for 50%), Cost

(.02 for high cost, .65 for low), and Better (.52 for Better, .16

for Worse). All differences were highly significant (p=.0000),

and no interaction was significant.

Table shows the means for Feelsum, the sum of the

two measures of how the subject felt about the two companies.

Both made the same decision, so this serves as an overall measure

of confidence in that decision. All of the first-order

interactions shown were highly significant (p=.0000): subjects

favored coverage more (larger difference between Not cover and

Cover) when the treatment was lower cost, when it cured 100%,

and when it was the Better option. No higher-order interaction

was significant.

Table 3: Means for Feelsum, the sum of how subjects felt about

the decision, as a function of cost, coverage, benefit and

betterness.

| Not cover | Cover |

| High cost | -0.45 | -0.24 |

| Low cost | -1.13 | 0.59 |

| 50% cure | -0.61 | -0.04 |

| 100% cure | -0.98 | 0.39 |

| Worse | -0.51 | -0.15 |

| Better | -1.07 | 0.50 |

Table shows the results for the questions about

how the subjects would feel about getting insurance from the two

companies, coded so that positive numbers represent better

feelings about B (the more thorough company). Here we could also

assess the interaction of Cost, Cure and Betterness with

Coverage. The interaction between Cost and Cover was significant

(t101=2.55, p=0.0122), as was that between Better and

Cover (t101=4.87, p=0.0000), but the interaction between

Cure and Cover was not significant. In general, though, people

feel better about B, the more thorough company, when it is

responsive to Cost and Betterness.

There was also a triple interaction between Betterness,

Comparing, and Coverage (t101=5.89, p=0.0000). This is

what we would expect if the increased trust resulting from

responsiveness to Betterness were found mainly when Company B

made the comparison so that it knew about Betterness. In other

words, Betterness affects trust only when Company B took the

trouble to find out about betterness.

Table 4: Differences in feeling about Company A and B, with

positive numbers indicating better feeling about B (the more

thorough company).

| Not compare | Compare |

| Not cover | Cover | Not cover | Cover |

| High cost | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| Low cost | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.65 |

| 50% cure | 0.16 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| 100% cure | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.63 |

| Worse | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.45 |

| Better | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.14 | 0.73 |

Table shows a parallel analysis for Trust, the

question about whether the subject would trust B more than A. In

this case, the interactions with Coverage were all significant:

Cost (t101=3.61, p=0.0005); Cure (t101=2.13,

p=0.0353); and Better (t101=4.87, p=0.0000). Again, the

triple interaction between Betterness, Comparison, and Coverage

was significant (t101=6.53, p=0.0000).

Table 5: Differences in trust in Company A and B, with

positive numbers indicating more trust for B (the more

thorough company).

| Not compare | Compare |

| Not cover | Cover | Not cover | Cover |

| High cost | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| Low cost | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.65 |

| 50% cure | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| 100% cure | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.64 |

| Worse | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Better | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.14 | 0.72 |

Again, the main results so far are consistent with the general

conclusion that trust increases when the decision maker adopts a

strategy of doing thorough analysis and following its

conclusions. Again, we asked whether such a strategy is

effective even when the subject disagrees with the decision to

which it leads, which was the same for both companies in each

case. Knowledge increased trust in Company B (the more thorough

company) when the decision was consistent with betterness (better

and covered, worse and not covered) even on just those pairs of

cases in which the subject disagreed with the agent's decision in

both cases in the pair (mean effect of 0.27, t84=3.66,

p=0.0004).

In this study, 6 subjects (6%) were significantly more trusting

of the company that did less analysis (A), after

correcting for multiple tests as in Experiment 1. As in

Experiment 1, the attempt to use the results of CBA in the

context of health coverage can actually reduce trust for some

people. The number is small enough, however, so that it seems

unlikely to become a majority even with a different method of

sampling.6

Experiment 3

The present experiment examines the effect of CBA on trust in a

more morally charged context. Subjects were presented with items

found in other studies to be morally objectionable even though

they might conceivably lead to good outcomes, such as cloning.

Many people think that cloning (for example) should be completely

prohibited. We asked whether they could trust a government agency

that would not prohibit it, if a CBA indicated that cloning was

useful in some cases. Of course, a demonstration that a

procedure is sometimes useful does not necessarily imply that an

agency could craft a rule that would permit it when it was useful

and prohibit it otherwise, but such a demonstration would provide

some justification for not banning the procedure totally. Are

people responsive to such a justification?

Method

One hundred and five subjects completed a questionnaire on the

World Wide Web. Their ages ranged from 20 to 74 (median 38);

27% were male; 13% were students. The questionnaire began:

Medical procedures

This questionnaire concerns some medical procedures that have

been much in the news recently, such as cloning. One issue is

whether qualified doctors should be allowed to do them if

patients want them.

Please assume that all of these procedures have been perfected so

that they are completely safe and have their intended

effect.

[There were then some brief definitions of terms used in the

cases: artificial insemination, cloning, in-vitro fertilization,

embryonic stem cells, Alzheimer's disease, prenatal genetic

testing, spina bifida.]

Many people object to procedures like cloning or abortion on

moral grounds. Note that you can object to a procedure on moral

grounds and still think that someone might benefit from it. Some

questions may require you to imagine this kind of conflict

situation.

Each item began with one of the following 16 procedures (the

numbers in brackets are mean responses to ALLOW, TRUST, and CBA

questions, respectively, as explained later).

- giving a drug to cause death in a terminally-ill patient with

un-treatable pain, who requested the drug, and who was judged to be

rational by two doctors [0.68, 0.52, 0.56]

- giving a drug (with no side effects) to enhance school performance

of normal children [-0.18, -0.30, -0.18]

- transplanting the organs of a person who left no record

(either written or verbal) of his willingness or unwillingness

to be an organ donor, in order to save the life of someone who

needed an organ [0.47, 0.41, 0.52]

- cloning an adult human, who had difficulty having a child,

to produce a child who would be raised by the adult [-0.16, -0.20, -0.18]

- cloning an adult human to produce a fetus, which would be

aborted and used for cells to save the adult's life [-0.09, -0.22, -0.18]

- cloning an adult human to produce a fetus, which would provide

cells to save the adult's life and which would then be born

and raised as the adult's child [0.16, 0.09, 0.16]

- using in-vitro fertilization to produce stem cells for

treatment of Alzheimer's disease [0.62, 0.35, 0.43]

- having a child because, after birth, it could be a bone-marrow

donor and save the life of another child [0.68, 0.49, 0.56]

- testing a fetus for sex and aborting it if it is a girl

[-0.87, -0.60, -0.64]

- testing a fetus for spina bifida and aborting it if it has

spina bifida [0.60, 0.37, 0.39]

- testing a fetus for IQ genes and aborting it if its expected IQ

is below average [-0.73, -0.62, -0.58]

- modifying the genes of an embryo so that, when it is born, it

will have a higher IQ [-0.45, -0.43, -0.35]

- cloning someone with desired traits so that these may be

passed on, such as an athletic champion or brilliant scientist

[-0.50, -0.50, -0.41]

- using in-vitro fertilization to have one's own child [0.85, 0.70, 0.77]

- using in-vitro fertilization and then having the egg implanted in

another (surrogate) woman, who would give up the baby at birth

[0.81, 0.71, 0.77]

- using artificial insemination to have a child with a desired trait,

by choosing a donor with this trait, such as intelligence [0.37, 0.24, 0.26

The items were presented in a random order chosen separately for

each subject, twice (in the same order for each subject - so

that some questions were maximally far apart). The subject

answered 4 questions in the first pass and five in the second

pass. Here I present only the questions relevant to this article

(ALLOW in the first pass, the others in the second):

ALLOW. Should the government allow this procedure? [Response options:

This should be allowed, so long as other laws are followed. This

should sometimes be allowed, with safeguards against abuse. This

should never be allowed, no matter how great the need.]

TRUST. Suppose two government agencies could have the power to decide

which medical procedures are prohibited. The two agencies are

similar, but agency P would prohibit this procedure completely

and agency N would not. Which agency would you trust more to

have the power to decide? [P; N]

CBA. Suppose that a team of economists and other

researchers did an analysis of the effect of allowing this

procedure under certain circumstances. The team reported that

the procedure could do some good in these circumstances, and

nobody would be harmed. In this case, which agency would you

then think should have the power to decide about prohibition?

Remember, agency P would prohibit this procedure and agency N

would not. [P; N]

Results

The mean answers to the ALLOW, TRUST, and CBA questions for each

item are shown above in brackets, respectively. ALLOW was scored

so that 1 favored allowing and -1 favored prohibition (with 0

representing "sometimes"). TRUST and CBA were scored so that 1

represented N (not prohibit) and -1 represented P (prohibit).

The main result was that CBA responses (empowerment after the CBA

showed benefit) were higher than TRUST responses (before the CBA;

t104=4.17, p=0.0001; the result was also in the same

direction for all but one of the items). In sum, subjects were

more willing to trust - i.e., give power to - an agency that

would allow the procedure when they were told that the a CBA had

shown that the procedure could be beneficial on the whole.

Again, we asked whether any subjects showed significantly less

trust with CBA than without it, the opposite result from that

just reported. In this case, no subject showed a significant

reversal.

Experiment 4: efficiency for social vs. individual

decisions

CBA is often criticized for being concerned with efficiency at

the expense of individual welfare. In the trade-off between cost

and benefit of medical treatments, for example, people may think

that they should get an effective treatment even if it is

extremely expensive. Yet many agencies want to impose some sort

of rationing based on CBA, and such rationing has been found to

strike many as unfair or immoral (Ubel, 2000). If people want

agencies to follow their individual preferences, they will oppose

any effort to ration expensive treatment. If, on the other hand,

people accept the need for rationing at a societal level, they

may tolerate it as a matter of policy, even if they would not

want it for themselves.

The last experiment compared decisions about the self to two

types of policy decisions: decisions about voting, and decisions

about which agency to trust. We hypothesized that self decisions

would favor greater benefit at the expense of greater cost,

compared to the two societal level decisions.

Note that this is not necessarily a matter of selfishness,

although it may appear that way to the subjects. When treatments

are provided by government or by insurers, someone must pay for

them, and the payers are ultimately the same people as those who

might need the treatment (at least over a range of treatments -

e.g., women do not get testicular cancer, but they do get breast

cancer more than men do). The situations described were

sufficiently general so that subjects had no good reason to think

that they would benefit more than would others, or pay less than

others, from a decision to provide an expensive treatment.

Likewise, acceptance of rationing would not make people less

altruistic, in a formal sense. Instead, true altruism would

consider both the health benefits and costs for others. If

people thought that others were like themselves, perfect altruism

would lead to the same preferences for self and others. Subjects

in this experiment are asked to assume that they are

typical.7 If subjects are more inclined to choose

cost-effectiveness in policy than for themselves, we can think of

this (formally described) as a kind of differential altruism, in

which they express more concern for others' finances than for

others' health, relative to what they want for themselves.

We hypothesize, however, that people will think differently about

the individual case because of the "identifiable victim effect"

(Jenni & Loewenstein, 1997; see also Baron, 1997, for a related

result). They tend to think of the benefit to individuals,

themselves, as solving a single problem, that of the individual,

with the cost spread over millions of people, each of whom does

not notice the difference.

Alternatively, the same result could arise from a kind of

misguided selfishness, in which people mistakenly think about the

benefit and not the cost when thinking about themselves, even

though the social decision involves the identical trade-off, on

the average, for everyone. Our experiment does not distinguish

these explanations, but it does show that people may accept

rationing by CBA at a policy level even when they oppose its

implications for themselves.

Method

One hundred and seventy-eight subjects completed the questionnaire

(ages 18-67, median 38); 30% were male; and 12% were students.

Treatments

This questionnaire concerns decisions about medical treatments

for one-time epidemics of new infectious diseases. The question

is what to do if the epidemic hits.

The diseases in question all have fatality rates of 10%. Each

disease will affect 1% of the population, without regard to age,

sex, race, or health status.

Nothing can be done to prevent infection. Everyone is equally at

risk. Thus, each person has a 1/1000 chance of death, unless

treatment is available.

There are 32 screens, each with 4 questions. Some screens may

look the same as others. They are not. The numbers are different.

Please pay attention to the numbers.

Some questions concern your own choices for yourself, and others

concern your nation. Imagine that you are typical of your nation

in terms of your ability to pay.

One question concerns the relative strengths of two arguments. I

am interested in cases where the relevance of an argument depends

on the kind of decision you are making. For example, some

arguments may be more relevant to decisions about yourself, or

other arguments may be more relevant to decisions about your

nation. Please read these carefully.

Suppose that your nation has both private health insurance and

government coverage for at least some treatments. Some questions

concern private insurance, and others concern government payment.

[Here is an example of an item:]

Reminders:

- Each person has a 1% chance of infection.

- 10% of those infected will die.

- An 'effective treatment' cures the infection and thus cuts

the chance of death in those infected by 10%.

- Treatments that cost more than $4,000,000 per life saved

are usually considered too expensive.

The government will pay for the treatment for all who get the disease.

Treatment X cures 100% at a cost of $50,000 per case treated -

$5,000,000 per life saved. The source of the money will be

determined later.

Treatment Y cures 50% at a cost of $8,000 per case treated -

$1,600,000 per life saved. The source of the money will be

determined later.

[Subjects did not see the names of the questions]

1. [Vote] Suppose the national government had to decide on X or Y, and

it has a vote (as part of another election). Which would you vote

for? ('Equal' means that you would abstain on this question.) [X

Y Equal]

2. [Trust] Suppose that two candidates in this national election argue

for different treatments.

Candidate X argues for X because it cures the most people.

Y argues for Y because it is the most cost effective.

Based on this information alone, which candidate would you trust

the most to make decisions like this in the future (on his/her

own)?

3. [Self] How would you choose between X and Y for yourself? (Suppose

you are typical of those affected in questions 1 and 2, in your

ability to pay.)

[The treatments were repeated as a reminder.]

4. Note that treatment X cures the most people, and treatment Y

is the most cost effective. Consider the relative strength of

these arguments.

Which argument is more relevant to each type of decision?

- CURES THE MOST PEOPLE is more relevant to deciding for myself,

and/or IS THE MOST COST EFFECTIVE is more relevant to what I

support for my nation.

- CURES THE MOST PEOPLE is more relevant to what I support for my

nation, and/or IS THE MOST COST EFFECTIVE is more relevant to

deciding for myself.

- The arguments do not differ in either of these ways.

The 32 items varied in whether the method of payment was

determined later (as in the example) or paid by those affected,

in which case the item read, "Your taxes [insurance premium]

will increase by [the cost per case treated divided by 100] for

one year." The purpose of this variation was to test the

hypothesis that people would be more willing to pay for something

when the source of the payment was unspecified. Otherwise, we

wanted to make clear that those who might need the treatment

would collectively pay for it, one way or another.

The items also varied in whether the treatment was provided by

government or insurance, and, orthogonally, in the cost of

Treatment X, the high-cost condition, which was either $50,000

(as in the example above) or $100,000 per treatment. (The

low-cost condition cost was always $8,000.)

Finally, there were four different price conditions, included

largely to create variation so that we could collect more data

from each subject:

- The high-cost treatment was 100% successful and the

low-cost treatment was 50% successful.

- 50% and 25% success, respectively, with the cost of each

treatment divided by two so that the cost per life saved was

the same as in condition 1.

- 100% and 25%, respectively, with the cost of the low-cost

treatment divided by two, again holding constant the cost per

life saved.

- The same as condition 1, but with all costs divided by 10

(so that even the high-cost treatment was within the usual

accepted range).

Results

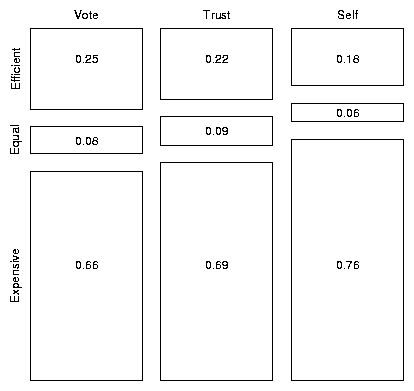

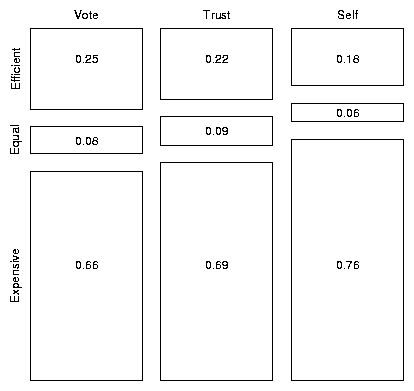

Figure shows the proportion of responses of each

type - favoring the expensive treatment (X), favoring the

efficient treatment (Y), equal - as a function of the question.

The main result is that, as hypothesized, the Trust question

(Which candidate would you trust?) and the Vote question (Which

treatment would you vote for?) each yielded more support for

efficiency than did the Self question (Which treatment would you

choose for yourself?). When responses were coded as 1 for

expensive and -1 for efficient, and the mean for each subject was

computed for the 32 questions, Self was higher than Vote

(t177=5.02, p=0.0000), and Self was higher than Trust

(t177=3.00, p=0.0031). (The Vote-Trust difference was

also significant, but we had no hypothesis about it.) In sum,

people were more accepting of efficiency considerations for

policy than for themselves.

Figure 1: Proportion of responses of each type as a function of

the question.

Figure 1: Proportion of responses of each type as a function of

the question.

These results were equally strong (and both significant) when the

case involved payment as when the source of funding was

unspecified. (The interactions with pay were approximately

zero.) In the pay condition, the cost to the taxpayer or policy

holder was the same, and specified, for all questions. We do not

take this lack of effect as a definitive refutation of the

hypothesis that people are more willing to demand costly policies

when the source of payment is unspecified. Rather, the

within-subject design may have led subjects to realize that,

indeed, someone has to pay.

Some subjects showed the reverse effects. The self-trust

difference was significantly negative (less expensive favored

more in the question about self than trust in an agency) for 7%

of the subjects. The same percentage showed a reversed effect

for the self-vote difference. Possibly these subjects did not

want to withhold an expensive treatment from others out of

stinginess about paying for it, even though they would be

unwilling to pay for it (through insurance) for themselves.

Question 4 concerned the relative strength of arguments about

cure rates and cost-effectiveness. On the average, more

responses indicated that the cure-rate argument was more relevant

to the self and the cost-effectiveness argument was more relevant

to the government than the reverse (t177=5.45, p=0.0000,

across subjects). (Three subjects, in comments, said they had

trouble understanding this question.) 55% of the subjects

showed a significant positive effect (cure-rate more relevant to

self) and 21% showed a significant reverse effect. The mean

response to Question 4 correlated .34 (p=.0000) with the

self-vote difference.

The different attitude toward the self was reflected in several

comments. Here are two of the longer ones: "Most all of my

answers were the same here. The reason for this was because when

deciding for myself, I will always choose the moral decision of

deciding to save the most lives. When it comes to putting some

one in charge of making the decisions for me, I feel that the

person making the cost effective choice is the best for the

economy. Although saving lives seems to be the most ethical, if

we have medical expenses rise that much, our budget will all be

out of whack." "I think anytime we can cure more people it

should be done unless determined too expensive is my view for

nation. As for myself I will always want the one that cures the

most, it may be bad to look at it that way but I suppose it's

like running a business with the nation and with myself there is

no room for debate. I want the one that cures the most

regardless."

Twenty percent of the subjects consistently chose the more

expensive treatment in all conditions. Typical of their comments

was, "I would not consider cost effectiveness when trying to

save lives." No subject consistently chose the more

cost-effective treatment.

The different cure-rate/price conditions were included mainly to

get more data and to create conditions that might lead to

within-subject variability. However, one result of interest was

that the expensive treatment was chosen more often in the third

conditions, with cure rates of 100% for the expensive treatment

vs. 25% for the efficient one, than in either of the first two

conditions (100% vs. 50%, 50% vs. 25%). Averaging across

all three measures (Vote, Self, Trust), the mean responses (with

1 favoring the expensive treatment) were .33, .32, .54, and .75,

for the four cure-rate/price conditions, respectively. The third

was significantly greater than either of the first two at

p=.0000 by t test for every comparison. Subjects seem to be

influenced by the large difference in cure rate, even though it

is balanced by a large difference in cost. The fourth condition

represented a lower cost for all treatments, and the responses

were higher than those of all other conditions, as they should be

by any account.

Conclusion

The results of Experiments 1 and 2 support the view that CBA,

when it involves comparison to alternatives and when its results

are acted upon, can increase trust in decisions. Although

Viscusi (2000) suggested the opposite, his results were weak

statistically, and many of them were limited to the very few

subjects who were least inclined to award punitive damages, as

almost all of his subjects did award such damages in all

conditions, leaving little room for any effects. In addition, as

Viscusi points out, the sizes of damage awards in his study may

have been larger with a larger value of life because subjects

anchored on the value when determining their award. The present

within-subject design apparently reduced such an anchoring

effect, so that the benefits of CBA could be seen.

Of interest in these experiments is that CBA increased trust even

when the subject disagreed with its conclusion. Thus, CBA can

apparently help win trust even among those who disagree with the

policy that is adopted, provided that people are adequately

informed about the basic reasoning behind the CBA.

Experiment 3 showed that trust could be increased by CBA, even in

highly charged moral contexts.

Experiment 4 found that people accept rationing on the basis of

cost more for social decisions than for individual ones. It is

not clear here which option is the true optimum in terms of

utility. (Health and life may be worth more than people are

willing to pay for them at a societal level.) People may feel

that their own life is worth more than the lives of others, but

the insurance context of the experiment implies that they would

be paying for others anyway. If they truly understand that

insurance implies that everyone pays and everyone (potentially)

benefits, then we could take their Self judgments as being

"real." People may not fully understand, however. When they

answer about themselves, they may focus on the idea that one

person is benefiting while everyone is paying. And they may

think, "For myself, cost is no object," without realizing that

their endorsement of this view implies the same for everyone.

It is also not clear whether CBA in general, properly done,

favors more spending or less on health care than is now spent,

but at some point CBA will limit spending. The experiment

indicates that people are willing to take cost into account, as

well as benefits, when evaluating a policy that affects many

people.

The use of a within-subject design had the main purpose of

increasing the statistical power of these studies, but it may

also have been unrealistic. Arguably, some decisions are made

without any comparison, such as the assignment of punitive

damages in legal cases. On the other hand, other real cases may

be modeled better by a within-subject design, such as a change in

policy. When an agency or company announces that it is going to

start doing CBA, people will naturally evaluate this change by

comparing the situation before the change with the situation

after it. Our results suggest that people will, in general,

perceive the adoption of CBA as a good thing.

References

Babcock, L., Gelfand, M., Small, D., & Stayn, H. (2003). The

propensity to initiate negotiations: toward a broader

understanding of negotiation behavior. Under review.

Baron, J. (1995). Blind justice: Fairness to groups and the

do-no-harm principle. Journal of Behavioral Decision

Making, 8, 71-83.

Baron, J. (1997). Confusion of relative and absolute risk in

valuation. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14, 301-309.

Baron, J. (1998). Judgment misguided: Intuition and

error in public decision making. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Baron, J. (2000). Thinking and deciding (3rd edition).

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Breyer, S. (1993). Breaking the vicious circle: Toward

effective risk regulation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

Press.

Dudoit, S., & Ge, Y. (2003). Bioconductor R packages for

multiple hypothesis testing: multtest.

http://www.bioconductor.org.

Jenni, K. E., & Loewenstein, G. (1997). Explaining

the"identifiable victim effect." Journal of Risk and

Uncertainty, 14, 235-257.

Kuran, T., & Sunstein, C. R. (1999). Availability cascades and

risk regulation. Stanford Law Review, 51, 683-768.

McDaniels, T. L. (1988). Comparing expressed and revealed

preferences for risk reduction: Different hazards and question

frames. Risk Analysis, 8, 593-604.

Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1990). Reluctance to vaccinate:

omission bias and ambiguity. Journal of Behavioral Decision

Making, 3, 263-277.

Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1999). Protected values and omission

bias. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 79, 79-94.

Slovic, P. (1998). Trust, emotion, sex, politics, and science:

Surveying the risk-assessment battlefield. In M. H. Bazerman, D.

M. Messck, A. E. Tenbrunsel, & K. A. Wade-Benzoni (Eds.)

Environment, ethics and behavior: The psychology of

environmental valuation and degradation, pp. 277-313. San

Francisco: New Lexington Press.

Tengs, T. O., Adams, M. E., Pliskin, J. S., Safran, D. G.,

Siegel, J. E., Weinstein, M. E., & Graham,

J. D. (1995). Five-hundred life-saving interventions and their

cost-effectiveness. Risk Analysis, 15, 360-390.

Ubel, P. A. (2000). Pricing Life: Why It's Time for

Health Care Rationing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ubel, P. A., DeKay, M. L., Baron, J., & Asch, D. A. (1996).

Cost effectiveness analysis in a setting of budget constraints:

Is it equitable? New England Journal of Medicine, 334,

1174-1177.

Ubel, P. A., Baron, J., & Asch, D. A. (2001).

Preference for equity as a framing effect. Medical

Decision Making, 21, 180-189.

Viscusi, W. K. (2000). Corporate risk analysis: A reckless act?

Stanford Law Review, 52, 547-597.

Westfall, P. H., & Young, S. S. (1993). Resampling-based

multiple testing: Examples and methods for p-value adjustment.

New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1993.

Footnotes:

1This work was supported by a grant

from the Russell Sage Foundation. Author's address:

Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, 3815

Walnut St., Philadelphia, PA 19104-6196

2Subjects were also more inclined to say

that the company should install the device than to say that the

agency should require it (.35 vs. .28, (t=2.82, p=.0058).

There is no hypothesis about this difference.

3Trust in B

was higher when the device is installed (the right two columns

of the table averaging .80) than when it is not installed (left

two columns .55, t=5.63, p=.0000), as if the thoroughness

mattered mainly when the agent did what most subjects thought

was the right thing, i.e., installing the device. But trust in

B was positive even when the device was not installed

(t94=9.94, p=0.0000).

4Company and agency did not differ.

5We also found a

triple interaction among knowledge, betterness, and benefit

[t=2.28, p = 0.0252]. The interaction between knowledge

and betterness was greater when benefit was higher [50 lives].

We find this difficult to interpret.

6Although men showed a smaller positive effect

of CBA on trust in Experiment 2 than did women, this result was

not found in Experiment 1, and it may thus be a fluke that

results from the small number of men in the sample, 29.

7Other data indicate that most subjects are

indeed typical for the U.S. population in income and education

(Babcock et al., 2003, whether they see themselves that way or

not.

File translated from

TEX

by

TTH,

version 3.40.

On 23 Nov 2003, 14:44.