(Penn)

kbrownle@sas.upenn.edu

M.S. Brownlee

(Princeton)

msb@princeton.edu

Athens, Thebes, and Mystra

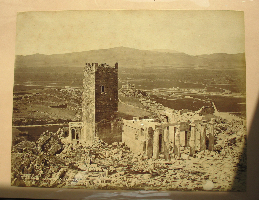

As recently as 1874, a Frankish tower still stood atop the powerfully symbolic Acropolis of Athens, a bold reminder of the city’s relentlessly contested fortune during the 13th and 14th centuries. The basic conflict, cultural as well as military, was between a series of Latin Western European invasders and settlers on the one hand, and the Byzantines as ell as Moreots, on the other. French was the official language not only of Athens and Thebes—a political entity known as the “Duchy of Athens” beginning in 1205—but of the Peloponnese (or Morea) as well, the whole entity being called the “Principality of Achaea”.

A byproduct of the Fourth Crusade that saw the defeat of the Byzantine empire by French forces, the Duchy encompassed the territories of Attica and Boeotia, and it remained intact until the Ottoman conquest of 1458. In 1205, a rather minor Burgundian knight, Otto de la Roche, assumed the title of “Lord of Athens” (Sire d’Athenes in French, Dominus Athenarum in Latin, and Μέγας Κύρης in Greek). A vassal of the Principality of Achaea, the Duchy remained in the hands of the la Roche family until 1308, when it passed into the hands of Walter V of Brienne—yet his was a short-lived reign of only three years stemming from a strategic mistake that would precipitously end Frankish control of this Crusader State.

Though it seemed like a wise move, Walter’s decision to employ the infamous Roger de Flor and his Catalan Company of ruthless mercenaries to fight against the enemy Byzantine states of Epirus and Nicaea was soon recognized as catastrophic. Though Roger himself was murdered in 1305, the Catalans persevered in their aggression, culminating in the 1311 Battle of Halmyros at which the Catalans seized control of the Duchy, making Catalan the official language and imposing the laws of Catalonia over the previous French and Byzantine-based laws of the Principality of Achaea.

The Catalanss were able to control the territory of Athens and Thebes for nearly eighty years, but in 1388 the Catalans were themselves defeated by the Florentine family of Nerio Acciaiuoli that had already secured acquisitions in the Peloponnese. Upon his death in 1394, Nerio bequeathed the Duchy to the Latin Church of the Virgin (Santa Maria di Atene) and named Venice the executor of his will. Seizing the moment, the Venetians construed this testamentary power as justification for seizing the Acropolis in 1397. However, the principal Venetian enemy Antonio I Acciaiuoli (the illegitimate son of Nerio) ousted the Venetians in 1402, serving as Duke of the Duchy of Athens initially as a tributary to the Venitians and thereafter to the Turks during the period from 1402 to 1435. In 1456 the Turks seized the Acropolis, two years later (in 1458) converting the Acropolis into a mosque, thereby ending Latin rule over this territory.

Texts to be considered in the narration of events pertaining to the Duchy and its defeat by Catalans, Florentines, and Venetians will include the chronicles of Muntaner, Pachymeres and Grygoras, as well as the diary of Niccolo da Martoni. The six Byzantine romances written between the mid fourteenth and the early fifteenth century will also be studied. While their composition cannot be linked to Athens or Thebes, their focus on French, Catalan, and Italian models deserves commentary regarding the dialogue of the Byzantine east and Latin West, offering fascinating forms of translatio.

While Athens and Thebes during the mid-fourteenth to early fifteenth centuries did not exhibit the cultural prestige and political prominence that defines their ancient existence, Mystra is a different matter. Of all the Crusader States founded by the Franks, the Principality of the Morea was the most significant, led by its Prince, Geoffrey de Villardouin. Perceiving the strategic nature of the hill of Mystra, Geoffrey’s successor, William II de Villardouin built a castle, leading to the construction of a whole city, a center of learning that eventually gained it the title “the Florence of the East”. Georgios Gemistos Pletho (c. 1355-1452/54), a resident of the citadel of Mystra, was instrumental in the revival of Greek learning in Western Europe, credited ith the re-introduction of Platonic philosophy to Western Europe. Pletho convinced Cosimo de Medici to establish a new Platonic Academy, and it was there that Marsilio Ficino translated all of Plato’s works into Latin, as well as Plotinus and other Neoplatonists.