Janine Wedel

GATECRASHING DEMOCRACY

The Role of Elite Corruption in Today’s Illiberalism

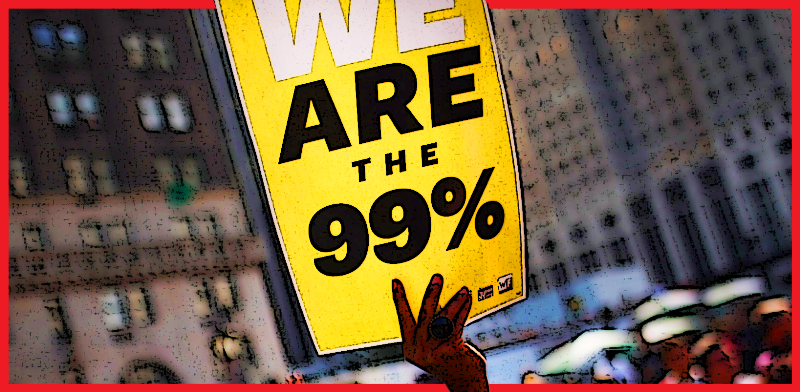

The present era of democratic fragility has been decades in the making. Establishment corruption, I contend, has led to the weakening of democracies from the United States and United Kingdom to Poland and Hungary to Greece and Italy. Pundits and scholars have looked largely to “populism” to explain the current state of affairs, with intense scrutiny devoted to the subject since the vote to “Brexit” and the election of Donald Trump.

Yet this punditry sometimes neglects the fact that anti-system movements (aka populism) that decry a “rigged system” did not suddenly erupt from nothing. Instead, certain transformational developments over recent decades, some facilitated by establishment players making self-serving policy decisions, helped create a precarious ecosystem that fueled the movements. They are substantially a reaction to new forms of power and influence—indeed even “corruption,” legal and systemic—on the part of elites that have become business as usual across the political spectrum. And, while analysts (belatedly) have taken notice of discontent among the populace, research on elites and their part in fostering it has been largely, if not willfully, disconnected. The survival of democracy as we know it may depend on grappling not only with the anti-system rage from below. What’s urgently needed is a full-fledged, inward-looking examination of the monumental evolution—and corruption—of those from above.

The threat that systemic elite corruption poses to stability is not new. Hannah Arendt examined its role in fomenting the movements that brought about the twin calamities of Nazism and Stalinism. She warned that establishment corruption can help mobilize action to get rid of it, and with it, the system.

Today, 70 years hence, that mobilization has reshaped the political terrain across Western democracies. The “populist” radical right now has double digit support in 22 European countries; twenty years ago, that share was just 5 percent. Two years after Trump’s election, his base and the Republic Party remain largely faithful. Uniting these movements from both the right and the left is a contempt for elites deemed to be working on behalf of their own ends andunresponsive to the needs of regular citizens. Corruption has been a pressing concern for many people,a sentiment upon which anti-system candidates have capitalized.

Jeffrey Green

HAS INEQUALITY LED TO A CRISIS OF LIBERALISM?

[Originally published in Current History, November 2017]

One of the differences between a crisis and a catastrophe is that with a catastrophe—whether environmental, financial, or military—there can be no doubt about its existence or general severity, whereas with a crisis there will be debate about whether it is happening at all. A crisis most basically refers to a threshold level at which an underlying system, whether practical or ideological, no longer seems viable in its current form. And the reason people can disagree about crises is that just what this threshold level is, and what the consequences will be for crossing it, usually remain uncertain. In the case of a catastrophe, such as a natural disaster, the collapse of an economy, or the descent of a state order into violence and civil war, the devastation is obvious and the likelihood of fundamental change hardly less clear.

The stresses currently experienced by contemporary liberalism fit much more obviously in the category of crisis, since the level of uncertainty—and, with it, the genuine possibility that not much will change ideologically or politically in the near term—is still quite high. Still, what undeniably gives our time the sense that liberalism is crisis-ridden is how clearly things have changed from the situation just a generation ago, when it seemed—in the immediate aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of communism in Eastern Europe—that the liberal system was nothing less than the culmination of world history, as Francis Fukuyama among others memorably asserted.

But what is the liberal system? It consists of at least four strands. Politically, it refers to a liberal-democratic regime, which strives to afford equal respect to its citizens, conceived as free and equal co-legislators of public affairs. From a religious perspective, liberalism stands for the idea that the public realm must not be colonized by a specific religious faith, but must separate and protect a space that is religiously neutral from a private sphere in which citizens are free to subscribe to sharply divergent religious ideas and practices. Economically, liberalism indicates the sanctity of private property as well as the mutual advantageousness of markets and the inequalities they generate (when they lead to gains for all). And ethically, liberalism celebrates the standpoint of the individual, both as the holder of rights whose protection is the deepest purpose of the liberal state and as the agent of a way of life shaped by choice, freedom, self-realization, and the broad cultural diversity these attributes generate.

The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy

The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy