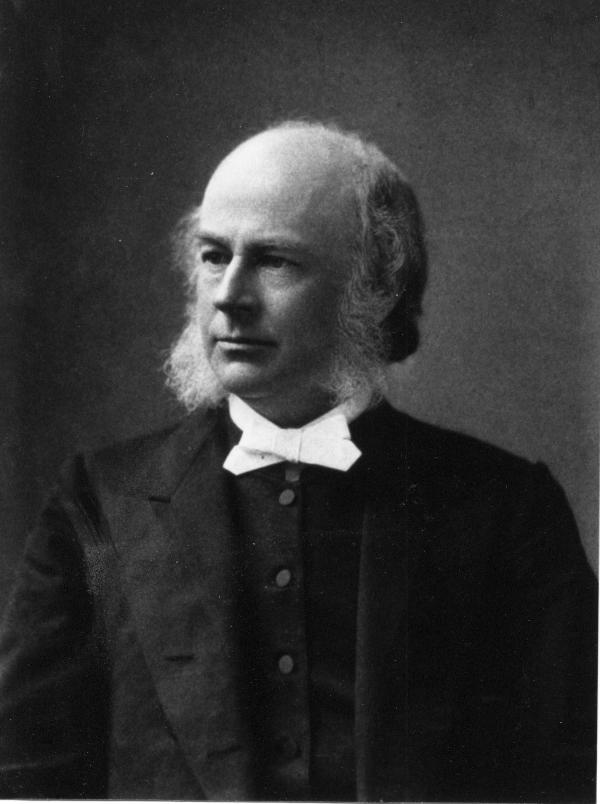

Cattell as a young man

Courtesy of Lafayette College Archives

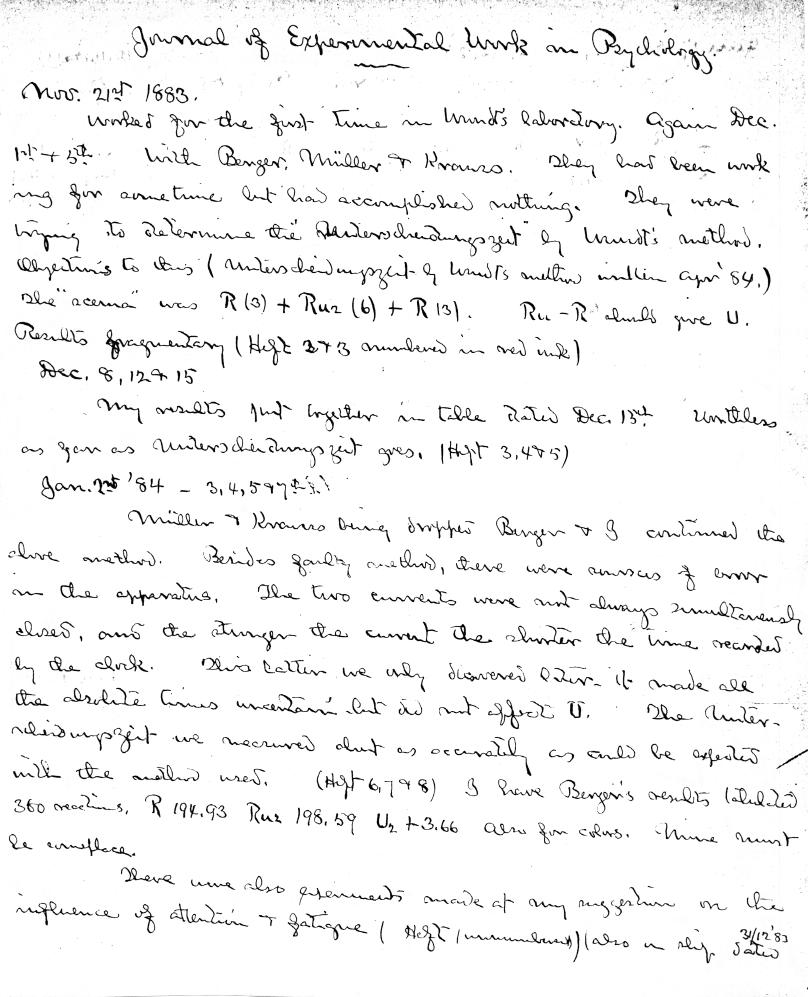

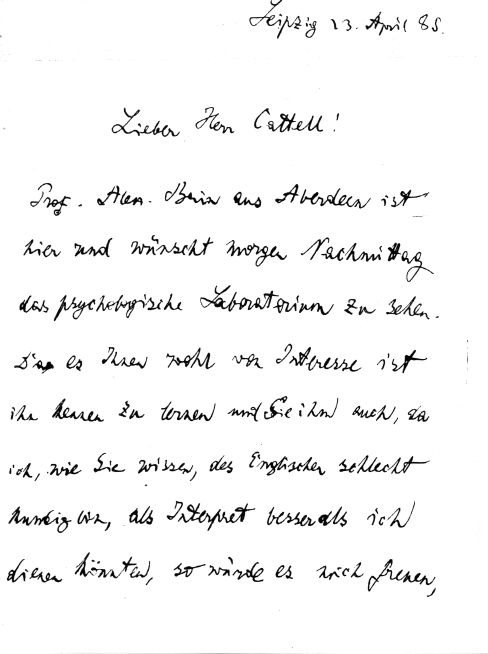

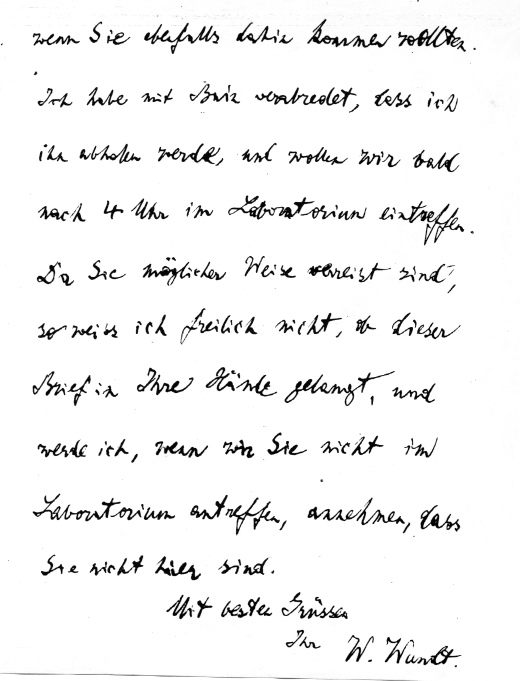

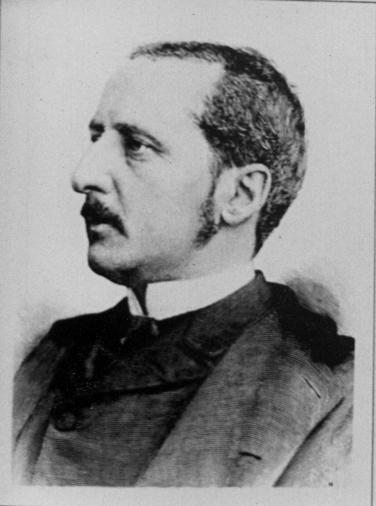

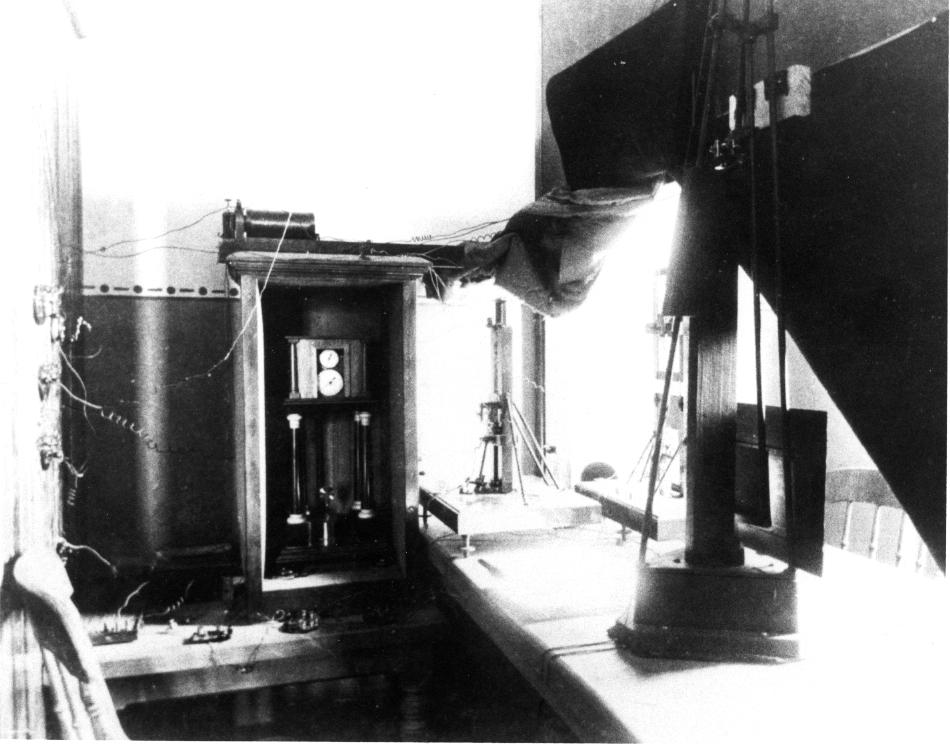

Wilhelm Wundt (1832-1920) founded the first experimental psychology laboratory at the University of Leipzig in 1879. In this laboratory, emphasis was placed on the study of introspection through the controlled and disciplined observation of one's own mind, often under well-specified stimulus conditions. Cattell was the first of about a score of American students to earn a PhD in experimental psychology.

Letter written by Cattell to his parents, from Cambridge on November 24, 1886. The Prof. Sidgwick in question is surely Henry Sidgwick, the utilitarian philosopher. Thus Cattell is expressing an interest in the problem of measuring utility (to the extent to which utility is to be identified with pleasure).

I have been writing today an essay on "The measurement of Pleasure" which I must read to Prof. Sidgwick's next Monday. It is an interesting and difficult question. What do you think? Can we ever say that one pleasure is twice as great as another?

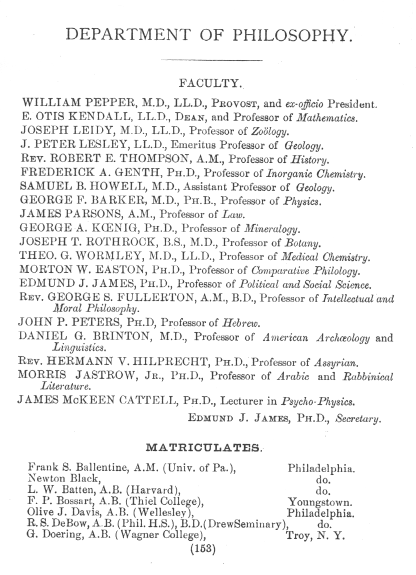

William Cattell, James's father and the president of Lafayette College, negotiated the appointment with William Pepper, provost of the University of Pennsylvania. The original position was as a lecturer but was then converted to professor of psycho-physics. The laboratory was established in 1888, following the appointment in 1887.

The following excerpts from letters between James Cattell and his parents describe something of the process of that appointment:

I scarcely know what more to tell you. It is not easy to describe any one, least of all the woman I love [Josephine Owen]. If there were things in which I do not think her perfect, I should not tell you of them, and all the praise I could write, you would take as a matter of course. She looks both younger and smaller than she is - she must be 5ft 3in tall, perhaps a little more, and weighs 115 lbs - which is easy enough to write but does not convey much. She was ill some when she was younger, having had scarlet fever three times, but is now in good health and very strong, at least has an immense deal of energy. We rowed down from Connewitz the other evening without stopping in 25 minutes - which Harry will tell you is very fast. Today we walked 6 or 7 miles before dinner, she had a music lesson in the afternoon and we went to the theater in the evening - it was Rienzi, the beginning of the Wagner cyclus - and she does not seem to be at all tired.

Now what more shall I say? I wish most of all you could see her. Perhaps it will decide you to come over this summer - that would be altogether pleasant. You will be quite delighted with your daughter. I imagine you thought it possible that I might marry an actress, socialist [sic], or such like - but everyone who knows "Jo" is fond of her [...]. All her girl friends and the people she lives with are extremely fond of her. She lives in a nice family - the widow of a professor - Harry knows the son Dr. Bruns. The little girl keeps following her and looking at her all the time. She and her brother are very fond of each other. I imagine half the men I have seen with her have been in love with her.

You see I am trying to give objective rather than subjective opinion - the latter being under the circumstances, if not less true, at all events less likely to be accepted as accurate. By way of further objective fact I might say that before leaving England she passed a "Local Examination" and had studied Latin, Geometry, etc. For the past two years she has been studying music here - and in America, at least, would be considered to be a very accomplished musician. She will give up continuous piano practicing - as we agree in thinking that it costs too much time - but will go on with her singing. I have not heard her sing - except in the choir at church - I imagine she has a good but not remarkable contralto voice. She has read a good deal - she understands and likes Shakespeare, Goethe, Browning, etc. She knows French as well as German. She likes to cook and sew. She designs her own frocks and dresses very prettily. She understands at once whatever I explain to her - she is anxious to help me in my work and quite able to. But it is not for these reasons that I love her - you will partly understand them when you meet her, partly they will perhaps remain my secret.

A page from the catalog of 1887-8. The "Department of

Philosophy" was apparently a general term that included most of

what we now call "Arts and Sciences."

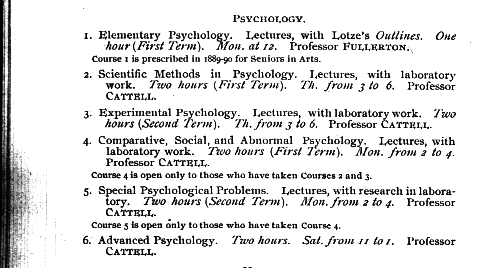

A page from the catalog of 1887-8. The "Department of

Philosophy" was apparently a general term that included most of

what we now call "Arts and Sciences."

Cattell was an extrememly prolific researcher and made contributions to the study of reaction time, association, perception and reading, psychophysics, determination of order of merit, and individual differences.

After he left Pennsylvania, Cattell continued to collect data on individual differences in simple mental tasks, such as reaction time. If fell to Cattell's student at Columbia, Clark Wissler, to figure out what to do with these data. (Wissler, C. [1901], The correlation of mental and physical tests. Psychological Review Monograph Supplements, 3, No. 6.) Applying Galton's new statistical method of correlation, Wissler found no relationships among Cattell's measures or between the measures and academic achievement. Dismayed, Cattell stopped collecting data (Sokal, p. 339). Ironically, in 1904, Charles Spearman argued that Cattell's tests failed because of poor measurement, not because the basic idea was flawed. Spearman carried out the same kind of program of testing and found substantial correlations, using them to argue for a general factor in intelligence in his classic 1904 article: "General intelligence," objectively determined and measured. American Journal of Psychology, 15, 201-293.

During World War I, he wrote a letter to several Congressmen urging them to "support a measure aginst sending conscripts to fight in Europe against their will." He had been against the war from the start, although once the war started he joined the Psychology Committee of the National Research Council, which organized and supervised psychological research. But he continued to be concerned about men who later came to be known as conscientious objectors.

He had already done many things at Columbia to irritate his colleagues. He was "combative, blunt, and altogether lacking in tact" (Gruber, 1972), and several efforts had already been made to get him dismissed. The letter was the last straw, and it led to dismissal, by the Trustees, on October 1, 1917. Many year later, after an extensive court battle, he was reinstated. Although most of his colleagues disliked him, many defended his "academic freedom," and his case provided fuel to the newly founded American Association of University Professors. Ultimately, the movement for academic freedom led to the general acceptance of the idea that academic freedom is an important part of being a professor, and, in particular, professors cannot be fired for the expression of political views, however unpopular they may be (Gruber, 1972).

Cattell devoted substantial energy to the ranking of men of all sciences in terms of their eminence. The following excerpt from his autobiography describes his perception of his own status:

"Certainly, I have no illusion that I am a figure in the world that will attract the interest or curiosity of the present or future public. My estimate, based on the attitude of others, is that I stand somewhere among the first hundred contemporary scientific men of the United States and also probably among the first hundred editors and promotors of science and education. This will put me among the first thousand in a Who's Who of the current sort, but that is not much. I have drawn up by objective methods a list of the thousand men most eminent in history, arranged in order of merit. The first ten of the last hundred are Gracchus, Delambre, Caligula, Edward II, Richardson, Prophyry, Nicole, Waller, Balboa, Solyman. Who knows or cares much about these men or would take the trouble to be greater than Gracchus?"