Frederick J. Evans, Mary R. Cook, Harvey D. Cohen, Emily Carota Orne, and Martin T. Orne

Abstract. Consistent subjective, behavioral, and electroencephalographic sleep-stage differences were found between afternoon naps of 11 habitual appetitive nappers (who nap lightly for psychological reasons apparently unrelated to reported sleep needs) and l0 replacement nappers (who apparently nap regularly in response to temporary sleep deficits). Both types of naps were compared with naps of 12 confirmed non-nappers.

Although the need for sleep is universal, extensive research has yet to clarify the functions of sleep, the efficiency with which it is obtained, and the mechanisms underlying the recovery from fatigue. Sleep is not a unitary phenomenon, and broad individual differences in the amount of sleep and its different stages are obtained. In addition, not all of an individual's sleep is obtained during nighttime hours; some individuals nap during the day. The functions served by daytime napping may differ widely among individuals. Like sleep in general, daytime napping is apt to serve functions other than physiological, restorative, and homeostatic ones. For many people a brief nap is reported to have restorative value far exceeding the length of time involved. In contrast, for some other individuals, the aftermath of napping seems to be sufficiently unpleasant that it is actively avoided.

To determine the frequency of napping in a young adult population and to evaluate whether there were differences among subjective experiences of napping, 430 college students were surveyed and patterns of napping and their attitudes toward napping were evaluated. Sixty percent of the students indicated they sometimes, usually, or always took catnaps during the day; only 40 percent answered they rarely or never napped. This finding is consistent with the frequency described in the literature (1) among a similar age group.

On the basis of criteria developed from pilot surveys, at least two different kinds of nappers could be identified from an analysis of these questionnaire descriptions of naps. (i) Replacement nappers nap to make up for previously (or soon to be) lost night sleep, and (ii) appetitive nappers nap primarily for reasons other than sleep need and apparently derive psychological benefits from the nap not directly related to the physiology of sleep. Specifically, a replacement napper was defined as a subject who had answered "no" to the criterion question "Do you nap even when you do not feel very tired?" and an appetitive napper was one who had responded either "definitely yes" or "possibly yes" to this question. A number of other questionnaire responses consistent with this distinction significantly differentiated between appetitive and replacement nappers. About 22 percent of the 261 nappers were classified as appetitive nappers, and 78 percent napped primarily for replacement reasons (2).

Subgroups of 11 appetitive and 10 replacement nappers (each of whom typically napped in the afternoon at least once a week), as well as 12 consistent non-nappers (who reported they rarely or never napped because napping had unpleasant mental and physical aftereffects) were asked to take a nap in a standard sleep laboratory. Subjects were included in the study only if an interviewer, who was unaware of the subjects' questionnaire responses, made the same classification as the questionnaire assignment. Thus, subgroup assignments were made by the independent classifications of both the questionnaire responses and a blind interviewer. Any subjects (particularly the non-nappers) who expressed doubts about being able to sleep in the laboratory were assured that the physiological data would be valuable even if they only rested quietly.

Standard electroencephalographic (EEG) and electrooculographic (EOG) recording electrodes were applied by an experimenter who was blind as to the subjects' napping classification. Subjects were provided with a comfortable bed in which to take a nap. Although the length of the nap was not discussed, subjects were aroused by a loud telephone buzzer 60 minutes after they were asked to begin their nap. Arousal reaction time, defined as the time taken to pick up the

687

688

telephone, as well as alpha-onset arousal latency was recorded. A number of rating scales were administered to evaluate tiredness, recovery from fatigue, and satisfaction with the nap. Subjects were scheduled in such a way that no naps began before noon nor later than 5:30 p.m. The physiological records of the nap period were scored blind with regard to nap classification in 30-second epochs, according to the conventional method of scoring EEG sleep stages described by Rechtschaffen and Kales (3).

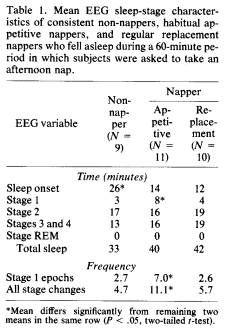

Of the 12 habitual non-nappers, nine were indeed able to fall asleep in the laboratory. Some of the variables of the nap for the three subgroups are presented in Table 1.

Sleep onset latency is significantly shorter for both napper groups than the non-nappers (4). This result is consistent with other questionnaire data, which indicate that an important characteristic of nappers is their voluntary control over sleep; they can fall asleep easily in a wide variety of circumstances, whenever they choose to do so.

As expected, virtually no rapid eye movement (REM) sleep appears in the afternoon naps (5). The amount of sleep stages 2 and 3 and total time asleep are similar for the three subgroups.

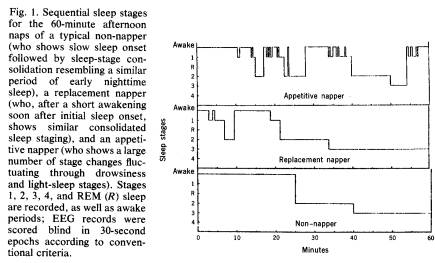

With the exception of sleep onset latency, the sleep stages of the non-nappers and replacement nappers are similar and resemble periods of consolidated sleep of the kind seen early in the night. The nap of the appetitive napper, however, is quite different. Although the amount of time spent in the various stages is similar, the distribution of these stages differs from the other two subgroups. The appetitive napper has significantly more epochs (lasting 30 seconds) of stage 1 sleep and also significantly more changes in sleep stage than the oth-

er two groups. Thus, the appetitive napper's sleep record shows a marked tendency to fluctuate between drowsiness, stage 1, and stage 2 sleep. Individual sequential sleep-stage distributions illustrating some of these differences in a typical nap of a non-napper, a replacement napper, and an appetitive napper are shown in Fig. 1.

No differences in subjective depth of sleep were reported by subjects in the three subgroups. Consistent with their earlier questionnaire responses, nappers reported feeling less tired and sleepy after the nap, whereas non-nappers did not. Similarly, non-nappers were significantly less satisfied with the nap and derived less subjective benefit from it. However, the decrease in fatigue and the positive rating of nap satisfaction are not apparent in the nappers until after they have been awake for several minutes. Other pilot data have indicated performance increments within a few minutes after arousal but not immediately on arousal from short naps. Performance improvements have been recently reported in habitual nappers following 1/2- or 2-hour naps (6).

After the nap, subjects were asked to complete 15-day sleep diaries. Data concerning frequency as well as the parameters of napping and nighttime sleep support the important psychological and physiological differences found in the two kinds of nap. Day-by-day analyses of the sleep diaries show that replacement nappers report having taken naps only on those days when, for the preceding 1 or more days, they described specific sleep deficits; that is, replacement nappers had typically gone to bed later than usual and slept less than usual on nights before days on which they napped. In contrast, for the appetitive napper there are no significant differences in reported sleep onset latency, length of sleep, and quality of sleep between non-nap nights and either the nights before or after naps.

In general, there are at least two distinctive kinds of naps that not only have different subjective characteristics but also differ in EEG sleep-stage characteristics (7). Napping appears to serve different but important functions for different kinds of individuals. These functions are reflected in the subjective reports describing napping habits, in the physiological activity that characterizes the different kinds of naps, in the subjective changes that follow napping, as well as in detailed sleep diary patterns. Some people have the capacity to nap as needed to compensate for accumulated sleep deficits; others use the nap primarily for psychological restorative functions seemingly unrelated to sleep needs (8). Future work will need to clarify the functions served by these two kinds of naps and their relative significance for recovery from fatigue as well as for the ongoing psychological health of the individual.

FREDERICK J. EVANS

MARY R. COOK*

HARVEY D. COHEN*

EMILY CAROTA ORNE

MARTIN T. ORNE

Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital and University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia 19139

References and Notes

1. N. Kleitman, F. J. Mullin, N. R. Cooperman, S. Titelbaum, Sleep Characteristics: How They Vary and React to Changing Conditions in the Group and the Individual (Univ. of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1937); M. W. Johns, J. A. Gay, M. D. E. Goodyear, J. P. Masterton, Br. J. Prev. Soc. Med. 25, 236 (1971); B. E. Lawrence

689

thesis, University of Oklahoma (1971); G. S. Tune, Br. Med. J. 2, 269 (1968).

2. The results of this questionnaire survey have been replicated in another sample of 489 subjects (F. J. Evans, M. R. Cook, H. D. Cohen, E. C. Orne, M. T. Orne, paper presented at the American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., 3 to 6 September 1976).

3. A. Rechtschaffen and A. Kales, Eds., A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects (Public Health Service, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1968).

4. All reported differences are significant (P < .05, two-tailed t-test).

5. Studies by I. Karacan, R. L. Williams, W. W. Finley, and C. J. Hursch [Biol. Psychiatry 2, 391 (1970)]; L. Maron, A. Rechtschaffen, and E. A. Wolpert [Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 11, 503 (1964)]; and W. B. Webb, H. W. Agnew, and H. Sternthal [Psychonom. Sci. 6, 277 (1966)] have shown that REM sleep typically occurs in naps of less than about 1/2 hours only if they are taken early in the morning.

6. J. M. Taub, P. E. Tanguay, D. Clarkson, J. Abnorm. Psychol. 85, 210 (1976).

7. A third type of napper who naps in response to stress-induced insomnia has been identified. Although the nap has EEG characteristics similar to those of a replacement nap, it is not satisfying and tends to interfere with the subsequent night's sleep, thereby maintaining the sleep disturbance that initially led to the nap itself.

8. Hypnagogic reverie tends to occur during these light-sleep, drowsy periods.

9. Supported in part by U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command contract DADA 17-71-C-1120 and in part by a grant from the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry. Aspects of these data were presented at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Association for the Psychophysiological Study of Sleep, Cincinnati, Ohio, 3 June 1976. We thank B. E. Lawrence, W. M. Waid, S. K. Wilson, P. A. Markowsky, and H. M. Pettinati for their helpful comments during the preparation of this report; C. Graham, who introduced subjects to the study and, where necessary, appropriately allayed subjects' anxieties about their inability to nap in a laboratory setting; and B. R. Wells and A. L. Van Campen, N. K. Bauer, J. P. DeLong, E. F. Grabiec, J. E. Hamos, M. L. Korn, A. M. Myers, L. L. Pyles, and J. Rosellini, for technical assistance. We also wish to thank H. Gleitman, who allowed his class to volunteer for the questionnaire survey.

* Present address: Midwest Research Institute, Kansas City, Missouri 64110.

20 August 1976; revised 26 January 1977