THOMAS H. McGLASHAN, MD,* FREDERICK J. EVANS, PhD, and MARTIN T. ORNE, MD, PhD

The effects of hypnotically induced analgesia and placebo response to "a powerful analgesic drug" were investigated. Highly motivated Ss, who were either very responsive or essentially insusceptible to hypnosis, performed a task which induced ischemic muscle pain. Special procedures and a modified double-blind condition were adopted to establish plausible expectations in both groups that the two treatments effectively reduce pain intensity. Changes in pain threshold and tolerance following hypnotic and placebo analgesia (compared to an initial base-level performance), were evaluated and were related to changes in the Ss' subjective ratings of pain intensity. The results support the hypothesis that there are two components involved in hypnotic analgesia: One component can be accounted for by the nonspecific or placebo effects of using hypnosis as a method of treatment; the other may be conceptualized as a distortion of perception specifically induced during deep hypnosis.

ALTHOUGH dramatic demonstrations of the use of hypnotically induced anesthesia during major surgery have been reported, 9, 23, 24 controlled experimental studies have not objectively substantiated its effectiveness.1, 2, 14, 30, 31, 34 A similar paradox exists concerning the pharmacological effects of analgesic agents. Although opiates, known since antiquity, are potent analgesic drugs, their effects on pain thresholds have been difficult to demonstrate experimentally.4,5

Review

Pain as a Complex Experience

Pain usually depends upon the stimulation of specific end-organ receptors. Subjectively, however, pain intensity does not necessarily reflect the level of stimulation, the extent of tissue damage, or the danger to the organism. Psychological factors, such as the meaning

From the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and the Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Supported in part by Contract Nonr 4731(00) from the Office of Naval Research.

We wish to thank J. M. Dittborn, C. F Holland, K. Hurson, J. J. Lynch, E. P. Nace, U. Neisser, D. N. O'Connell, Emily C. Orne, D. A. Paskewitz, C. W. Perry, and P. W. Sheehan for their helpful comments during the preparation of this report, and Mrs. Mary Louise Burke and Mrs. JoAnne Withington for their considerable editorial assistance.

Received for publication Dec 16, 1968; revision received March 19, 1969.

*Present address: Massachusetts Mental Health Center, Boston, Mass.

227

228 Hypnotic Analgesia

ascribed to the sensation, past experience, and anxiety contribute to the individual's response to pain.

Beecher 4 introduced a useful conceptual distinction between the primary and secondary components of the pain experience. The primary component is the pain sensation itself, which includes the perception, discrimination, and recognition of the noxious stimulus. The secondary component, involves the suffering, reactive aspects, and includes anxiety, and emotional responses to pain. The psychological reaction to pain is considered to be independent of the primary sensation and is probably responsible for many changes in peripheral autonomic activity -- eg, heart rate, blood pressure, galvanic skin response -- which are normally associated with painful stimulation. This distinction raises the problem of selecting appropriate criteria to evaluate pain. In a careful review, Sternbach 33 documents the relative independence of the objective intensity of stimulation, the subjective experience elicited by stimulation, and the physiological measures of response. This study requires both subjective and objective measures of pain response; because of the difficulties in interpreting physiological responses to painful stimuli (see the discussion of Shor's research 30,31 below), we chose both subjective ratings and objective behavioral measures of pain, which vary in a lawful fashion with the subjective report of pain and are readily affected by analgesic agents. 4,18

Placebo and Hypnotic Analgesia

Many studies have shown that a pharmacologically inert substance (a placebo), administered as if it were an active drug, can act as a powerful analgesic agent. The effectiveness of placebo analgesia depends upon a variety of situational and motivational variables. It is more effective in a clinical setting than in an experimental situation.4

Several studies have shown a relationship between anxiety reduction and pain alleviation. 16,19, 25 Placebos apparently act upon the secondary component of pain, particularly by reducing anxiety. Laboratory methods of inducing pain, particularly by electric shock, are usually different in kind, momentary and not so intense, and not so threatening to the individual as clinical pain. The ineffectiveness of a placebo in experimental studies may be due to the relative absence of anxiety accompanying experimentally induced pain.

Recent views of hypnotic analgesia have followed a similar logic: Hypnotic analgesia works by reducing the secondary (anxiety) component of the total pain experience. 2, 30 Shor,31 for example, failed to find differences in GSR response when the S reported that the same level of electric shock which was painful in the waking state was much less painful during hypnotic analgesia. He ascribed this to a design which intentionally reduced the S's anxiety. Conceptualized in this fashion, hypnotic analgesia is implicitly analogous to the placebo response; both act on the secondary component of pain by reducing anxiety and have little effect on the primary sensation itself.

The placebo response has been considered traditionally as a manifestation of an individual's "suggestibility."2,13,17,29 However, reviewing the available literature, Evans10 concluded that the evidence did not indicate a relationship between suggestibility and the placebo response, although results from clinical studies were equivocal. We hypothesize, then, that any relationship that has been observed between hypnosis and the placebo response is best explained by common situational factors rather than by any special characteristic of the person.

Nonspecific Placebo Effects of Expected Treatment

When associated with ingesting active drugs, the placebo effect, broadly con-

229 McGlashan et al.

ceived, occurs in a situation surrounded by an aura of expectancy and implied change. Because of the patient's belief that the medication should work, changes in behavior or experience are anticipated. In this sense, the placebo response is a nonspecific effect of the drug treatment. Similar nonspecific or placebo effects occur with other forms of treatment, including psychotherapy, 13, 17,29 surgery, 5 and, we postulate, hypnosis. When a S believes hypnosis will relieve pain, similar nonspecific or "placebo" factors may operate as when a S believes a potent drug will relieve pain. Such nonspecific effects would be quite independent of the real pharmacological action of the drug and the real effect (if any) of the hypnotic analgesia on pain.

Hypnotic Analgesia as a Distortion of Perception

Hypnotically induced localized glove analgesia, which can be induced in a large proportion of Ss, usually is tested by relatively minor pain stimuli slightly above threshold, such as pinching or a weak electric current. Some of these apparent analgesic responses may be accounted for by the mildness and ambiguity of the stimulus and the possible anxiety-reducing effects of the hypnotic procedure. In order to explain the hypnotized patient's apparent failure to experience pain during major surgery, however, a different mechanism would have to be postulated. This mechanism would not act merely to reduce anxiety, thereby affecting the secondary component of pain perception, but would alter the individual's perception of the pain sensation. The altered perception, of the pain sensation induced by hypnosis would be analogous to other hypnotically induced negative hallucinations and is in addition to the relief induced by the placebo aspects of the hypnotic treatment.

Hypnotically induced analgesia may work in two different ways. The placebo effects of the hypnotic treatment situation may reduce the intensity of pain with all Ss who believe in the plausibility of the effectiveness of hypnosis, regardless of their susceptibility to hypnosis. In addition, a pain-reducing sensory alteration might be induced by hypnosis, but only for the few Ss who can be deeply hypnotized.

The distinction between the effects of the conditions surrounding the use of hypnosis and the state of being hypnotized is not a new one .28 Its validity has been shown both experimentally and clinically. London and Fuhrer22 were the first investigators to document empirically that the hypnotic situation may markedly affect unhypnotizable Ss. Weitzenhoffer 36 and others have emphasized that the therapeutic response to suggestion is often unrelated to the depth of hypnosis attained. Thus, there may be demonstrable effects of entering into a hypnotic relationship regardless of the S's ability to experience the kind of perceptual distortions which traditionally have been considered to characterize deep hypnosis. Similarly, the placebo response to "drug" treatment is largely a function of situational variables operating independently of the specific pharmacological action of the drug.

Aims of the Study

This experimental study was designed to evaluate the hypothesis that there are at least two mechanisms involved in hypnotically induced analgesia. One component can be accounted for by the nonspecific placebo effects of using hypnosis as a method of treatment; the other is conceptualized as a distortion of the perception of the pain sensation specifically induced during deep hypnosis, possibly by mechanisms similar to other negative hallucinations. In addition, we investigated the relationship between these two components of the pain experi-

230 Hypnotic Analgesia

ence during hypnosis, and a placebo response obtained when the S was administered a pill which he could plausibly believe was a powerful analgesic.

Rationale of the Procedure

Separating the specific effect of hypnotically induced analgesia from the nonspecific placebo component of the hypnotic relationship involves problems similar to those of separating the analgesic effect of a drug from its associated placebo component. The response to the drug is compared to the response to a placebo: It is necessary to create an analogous situation with hypnosis. A deeply hypnotized individual will respond to the hypnotic suggestion of analgesia as well as to those effects which can be better ascribed to the hypnotic relationship. In this relationship the hypnotist treats the hypnotized S quite differently from the waking S; in addition the S believes certain changes may take place. This situation will in itself induce certain changes best conceptualized as a form of placebo effect. What is needed, then, are Ss who do not respond to hypnotic suggestion but who are exposed to the hypnotic situation.

The ability of individuals to respond to hypnotic suggestions varies widely. The extent of any particular S's response, however, tends to be remarkably stable, especially after several sessions. London and Fuhrer 22 took advantage of this fact and proposed a design to study the effect of hypnosis by administering identical suggestions to both highly hypnotizable and essentially unhypnotizable Ss. If a response is due to the presence of hypnosis, then it should be present only in the hypnotizable Ss; but if it is due to other factors, then its presence would be randomly or equally distributed in both groups. After inducing hypnosis, changes in scores on some learning and performance tests were as large (sometimes larger) for the insusceptible Ss as for the susceptible Ss. 22 This ingenious procedure made it possible to study the placebo effects of hypnosis. It was necessary that the unhypnotizable S was convinced that he was, in fact, capable of responding to the hypnotic suggestions, just as when using a placebo the S has to be convinced that it has a plausible pharmacological action. An appropriate modification of this design was adopted for the present study.

The experiment consisted of three sessions: base-level control, hypnotic analgesia, and placebo analgesia. Two groups of Ss were drawn from the extreme (approximately 5%) of the range of those susceptible to hypnosis. A special procedure was introduced after the control session to convince the Ss who had shown themselves to be insusceptible to hypnosis that they were nonetheless able to respond to hypnotic suggestions of analgesia. Prior work in our laboratory had shown that Ss were capable of evaluating their hypnotic performance, 31 and the work suggested that it was vital to include a special procedure of this kind in order to have an appropriate model to study the placebo effects of using hypnosis. Both highly hypnotizable Ss, and unhypnotizable Ss who had been convinced by a special procedure of their ability to respond to suggestions of hypnotic analgesia, were tested by another E who, because he was unaware of their hypnotizability, was more likely to treat them in an identical fashion. Both groups were exposed to the placebo components of the hypnotic relationship, but only the hypnotizable group would be responding to the specific hypnotic suggestion of analgesia.

Placebo Analgesia

To determine whether pain relief attributable to hypnosis is qualitatively different from placebo analgesia, comparable expectations of pain relief were communicated in both hypnosis and

231 McGlashan et al.

placebo sessions. As Ss are often sophisticated enough to recognize the possibility of placebo medication, it was necessary to legitimize to Ss why a "drug" should be used in the experiment in order to maximize the placebo response.

Unlike other laboratory studies in which these Ss had participated, the present study emphasized overtones of "medical" rather than "psychological" research. At the beginning of the experiment, a medical history and brief physical examination were conducted by the E. After the session testing hypnotic analgesia, the Ss were told that a powerful analgesic drug was to be used as a control to evaluate the effects of hypnotic analgesia. It was conveyed that this drug was more reliably effective than hypnosis, and thus provided an upper limit of pain relief. (Because of the manipulation of expectations, it was decided that counterbalancing of the hypnosis and placebo sessions would not be desirable.) By using these methods, many of the special situational accouterments of a medical-treatment setting were duplicated in the experimental context.

A placebo, packed in a Darvon Compound-65 capsule, was given to each S. Except for one of the authors, who had no contact with the Ss during this study, all laboratory personnel (including the remaining two authors) were under the impression that half of the capsules contained placebo and half contained active Darvon Compound-65 (a mild nonnarcotic analgesic with potency comparable with aspirin 18). Capsules were assigned randomly to the Ss. No one (Es included) was informed that all pills contained placebo until after all the Ss had completed the experiment. This served two purposes. First, by being blind, the E would be able to project positive expectations about the effectiveness of the "drug" rather than possibly projecting a negative expectation about the ineffectiveness of placebo. Second, all of the special advantages of the double-blind methodology were attained without using an active pharmacological agent.

Method

There were three sessions, each separated by at least 48 hr. The Ss were not informed that subsequent sessions would be held until they had successfully completed the preceding ones.

Selection of Subjects

All 24 paid male volunteer college students who completed the three sessions had previously taken part in hypnosis experiments in the laboratory. They were solicited for the present study by telephone. The Ss were told that pain and hypnosis would be involved.

Three special qualifications had to be met if a S was to participate in the study.

Susceptibility to Hypnosis

The two subgroups of 12 Ss were selected from the extreme (approximately 5%) upper and lower ranges of those susceptible to hypnosis. All Ss had been administered the Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility: Form A (HGSHS:A); 32 the Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale: Form C (SHSS:C);37 and had been given at least two clinical diagnostic ratings. 28 The "high" group consistently experienced all classic hypnotic phenomena. They had at least two consecutive ratings of 5 -- on a five-point diagnostic scale assessing plateau hypnotizability. Their mean scores on HGSHS: A and SHSS: C were 10.08 and 10.25, respectively. The "low" group was consistently insusceptible to hypnosis during the standardized scales and at least two diagnostic sessions. They received no ratings higher than 2 --,28 and consistently failed to respond to any suggestion except the simplest ideomotor items. Their mean HGSHS:A and SHSS:C scores were 3.17 and 1.75, respectively.

The E, did not know the Ss' hypnosis ratings, and he was not told whether they were high or low Ss. During the hypnosis session, no attempt was made to evaluate

232 Hypnotic Analgesia

depth of hypnosis -- only analgesia was induced. These Ss were accustomed to a brief, relatively standardized induction procedure.

History and Physical Examination

During the first session, each S completed a medical history which focused on his cardiovascular system. A physical examination was conducted which included a modified Rumpel-Leede test of capillary fragility using a petechiometer. 6 Two Ss with physical or emotional conditions that might conceivably have been compromised by the experimental task were excluded.

Several other safeguards were observed for the S. The nature of the pain task was fully explained to the S before the experiment, and it was emphasized that he could discontinue at any time before or during the induction of pain. During the third session, the S could have refused to take the medication. He was not released from the "drug" session until he was "free from all side effects," determined by a subjective symptom checklist. Except for one S who could not be rescheduled for the "drug" session, no S refused either the pain task or the drug.

Hypnotic Analgesia

The highly susceptible Ss were required to achieve effective hypnotic glove analgesia, measured by a response to moderate electric shock applied to the S's dominant forearm. This was conducted at the end of Session 1 by E2,* who had not met the Ss previously. Waking threshold to shock was determined. Hypnosis was then induced, and suggestions of analgesia were given. All susceptible Ss reported they felt no pain at a level considerably above threshold.

With the design introduced by London and Fuhrer, 22 insusceptible Ss are told that they are good Ss for the purpose of the study in order to motivate them as much as possible for their hypnotic performance. In this study an attempt was made to convince them that they really were good Ss for the experiment by demonstrating to them that they could experience hypnotically induced analgesia. This was accomplished by the following method. Waking threshold was determined, and a second shock, uncomfortably above threshold, was administered. The S was told by E2 that this was the standard level of shock to be used during hypnosis in the next session. Hypnosis was then induced carefully, using a procedure based on relaxation. This method was purposively different from the induction techniques used previously. The deep relaxation experienced by the S was utilized to help convince the S of the effects of the new procedure. Hypnotic analgesia was then suggested, and a shock midway between threshold and the previously administered standard was given. Extensive postexperimental inquiries were carried out by E2, and only those Ss who seemed convinced that this was the same level of shock they had received in the waking state -- convinced that they had actually experienced mild glove analgesia -- qualified for the experiment. One S was excluded on this basis. The impression about the effect of this procedure was confirmed by E3 in postexperimental inquiries following the third session.

Ischemic Muscle Pain

Rationale

When arterial blood flow is occluded by applying a tourniquet to the upper arm, ischemic muscle pain is experienced after a relatively short interval of time. This pain involves a dull aching sensation which increases in intensity with increasing ischemia. The pain is related both to the length of time the tourniquet is applied and the amount of work carried out while the tourniquet is in place. 7, 3, 20

Ischemic pain has many of the qualities of clinical pain. Unlike electric shock, ischemic pain is not a transient sensation. Another advantage is that the S controls the rate of work and, consequently, the amount of pain experienced.

Procedure

The apparatus 21 consisted of a closed 6-liter flask filled with water. A rubber tube connected this to a double-valved rubber bulb. When the bulb was squeezed, water

233 McGlashan et al.

was forced from the flask through another rubber tube connected to a collecting beaker. The amount of water pumped from the flask was proportional to the force applied to the bulb, although, because of the changing water level and air compressibility factors, there was not a direct linear function.

The cuff of a portable mercury sphygmomanometer was placed on the upper arm. The seated S held his arm above his head for 1 min, and an electronic metronome was started at 40 beats/min. At the end of 1 min, the cuff was inflated to 200 mm Hg (which was well above systolic pressure in all cases). The S was told to lower his arm, was given the bulb, and was told to commence squeezing in time with the metronome. The S could not see how much water he had displaced.

In order to determine threshold, the S was asked to report the point at which the pain was first experienced. At this point, El immediately switched the outlet tube to another beaker while the S continued pumping. When the S could tolerate the pain no longer he dropped the bulb, and El deflated the cuff. The amount of water displaced and the time taken to reach pain threshold and pain tolerance were both recorded. If the S lost time with the metronome, he was warned once that he must keep time -- if he lost time again the trial stopped.

Procedure

Session 1: Baseline Pain Response

When the S had satisfactorily completed the history and physical examination, El read instructions explaining the task and the sensations to be expected. The S was told that he would recognize four stages of sensation as he pumped: (1) no change in sensation; (2) paresthesia, or the awareness of sensations that were not painful; (3) pain threshold, or the moment that sensations first became painful; (4) the maximum tolerable pain, or the point at which he could not possibly continue pumping.

A practice trial was administered using the S's nondominant arm. The S was instructed to pump only to pain threshold:

As you carry out this task, I want you to estimate for me when you have reached the beginning of Stage 3, that is, the beginning of the painful sensation. . . . Squeeze the bulb until you have reached the first sign of pain. When you have reached this point, which we call the threshold of pain, or the very least amount of pain that is discernible to you, say "Now," and stop squeezing the bulb immediately.

When the practice trial was completed, El refilled the large flask. Ten minutes later, the S was instructed to carry out the task using his dominant arm. After reporting threshold, as before, he was to continue pumping beyond this point; an attempt was made to motivate Ss as much as possible:

Now, as you continue pumping through Stage 3, the pain will increase in intensity until it becomes very unpleasant, and you will reach a point where you don't want to go on any further. Even then, I want you to make a maximum effort to go beyond this point. Whenever you feel you want to give up, keep trying a little bit more. It is absolutely crucial for the success of the experiment that you continue pressing almost beyond the limits of your endurance. When you have reached Stage 4, the end point, or that point where under no circumstances can you go on no matter how badly you may wish to do so, say "Now" again, and drop the bulb. Your arm will get very tired, but continue squeezing as hard as you can until it hurts so much that you cannot continue for even one more second.

At the completion of the task, the S was given a sheet of paper on which was a 5-in. line clearly marked with 10 equal divisions. The extremities were labeled "1," representing pain threshold, and "10," representing the absolute maximum pain that any person could tolerate. The S was asked to rate on this scale the intensity of pain he experienced at the point when he stopped pumping.

The clinical trial involving shock analgesia, described earlier, was then carried put by E2 in another setting. If the S qualified, he was scheduled by a research assistant for a subsequent session. He was told that

234 Hypnotic Analgesia

similar procedures would be followed, and that hypnosis would be involved.

Session 2: Hypnotic Analgesia

The S was reassured that he was an excellent S for this particular experiment, as he had passed the stringent qualifications of medical fitness and susceptibility to hypnotic analgesia. He was also assured that:

Having already experienced some form of hypnotic analgesia, your task will be easier today in that I am sure you won't experience anything near the amount of discomfort you experienced last time.

Hypnosis was induced for about 15 min by a standard procedure, involving eye fixation and counting, 37 that had been used previously with these Ss. Emphatic suggestions of dominant arm analgesia were administered for about 7 min. No specific tests of hypnotic depth were included in the induction to help keep E1 blind about the S's susceptibility to hypnosis. The ischemic pain task was presented to the S:

When I say start -- begin squeezing the bulb to the click of the metronome. If you happen to feel any unpleasant sensation, say "Now" if it is clearly discernible, just like last time. Then keep pressing as long as you possibly can, and continue to squeeze to the rhythm of the metronome up to the very limit of your tolerance -- painlessly. If you come to that limit and cannot keep pressing, say "Now" and drop the bulb, just like last time. It will be easier this time though, very easy, for there will be no pain to bother you. Your arm will not become tired or fatigued. It is deeply anesthetized, and you will remain alert, but deeply hypnotized.

When the task was completed, hypnosis was terminated, and the S was asked to rate both the intensity of pain and his self-estimated depth of hypnosis on 10-point scales.

A brief description of Session 3 was then read to the S. This explained that he would be asked to take an experimental pain-relief pill which was to be used as a control procedure so that the effectiveness of hypnotic analgesia could be evaluated. The S signed a release form for Session 3 signifying his agreement to take the experimental drug. He was then rescheduled by the same research assistant. The release form, not normally used in this laboratory, was similar to standard forms used in other laboratories studying drugs. It was used partly for interlaboratory standardization and partly to increase the plausibility for the S that an active drug was being used.

Session 3: Placebo Analgesia

The explanation of the third session* included information about the pharmacology of analgesia and the particular "drug" being used. Its virtues were extolled to the point of indicating its superiority over hypnotic analgesia:

Why are we using the drug then? Because hypnosis is psychological and therefore prone to all the variations that are inherent in a psychological phenomenon. This drug, on the other hand, is physiological and works on a physical or cellular level. Consequently, it is much more stable, reproducible, and uniformly more effective than hypnosis in producing pain relief or increasing performance. This is why we want to use it as a standard for measuring the efficacy of hypnosis, because we know how good it is and know its effects both quantitatively and qualitatively.

The S was told that the "drug" was a powerful new experimental analgesic named N-methyl-O-isopropyl oxazolidine. If he recognized the Darvon capsule he was told that, as the drug was still experimental and not available for commercial distribution, it had been packed in Darvon capsules for convenience.

The S ingested the capsule, and E1 left the room. The S was allowed to read magazines while E1 was absent. When E1 returned 35 min later, the ischemic pain task was administered to the S as before. A rating was obtained of the pain intensity experienced.

235 McGlashan et al.

A postexperimental inquiry was conducted by E3, who had previously conducted several experiments with these Ss. He discussed with the S his performance and perceptions of the purpose of the experiment. From a tape recording of the inquiry, another blind rater* made several ratings about the S's conviction of the use of a drug or a placebo, and rated the S's impressions about the effects of each experimental treatment.

Several psychological questionnaires, tests of suggestibility, and subjective symptom check lists, designed to measure drug side effects, were given to the Ss at different times during the experiment. Some results from these measures will be reported elsewhere.

Results

Four measures of ischemic muscle pain were analyzed for each session. Each S reported two measures of pain: threshold and total (the point at which they could not continue pumping); both the length of time and volume of water pumped were analyzed for each measure. In the double-blind third session, the Ss assigned to the "placebo" and "drug" subgroups did not differ statistically in their scores on any experimental measure, allowing the two subgroups to be combined.

Base-Level Performance During Ischemic Pain

Correlations between time pumped and cubic centimeters of water displaced to threshold (0.97) and total (0.89), although differing significantly (p = 0.03), reflect a highly constant rate of work. To the extent the measures differ, the amount of water pumped reflects work done, and length of time pumped reflects endurance. Pain threshold and pain tolerance measures were uncorrelated.

Figure 1 shows the length of time pumped during each of the three sessions for the high and low hypnosis groups. The significantly higher initial threshold of highly susceptible Ss compared with insusceptible Ss (time pumped, 82 and 60 sec, respectively, p < 0.025; cubic centimeters pumped, 1380 and 1002, respectively, p < 0.05) may reflect a true difference in pain threshold, or it may be that highly susceptible Ss are using a different criterion of threshold.

The initial threshold difference creates special problems for subsequent statistical analysis of the change scores. Of the several available alternatives, the change in performance from base level to treatment session was adjusted* by a function of the regression of the final upon the initial score as

Pain Relief During Hypnosis and Placebo

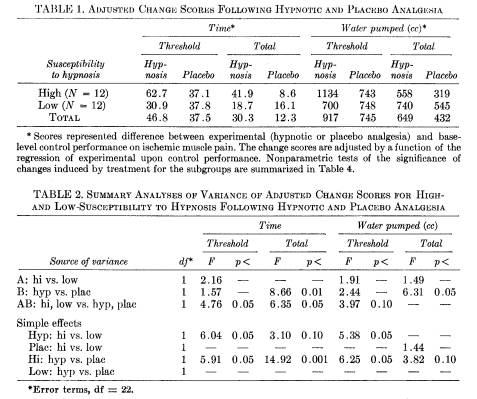

Adjusted change scores comparing high and low hypnotizable Ss on the four measures of response to pain are presented in Table 1. Pain relief, or at least an increased willingness to tolerate pain, is indicated by an increase in either the length of time S pumped or the volume of water pumped compared with the base-level session. Analyses of variance were conducted for each of the four adjusted change measures. The

*The adjusted change score d' = X1 - aY1 where the regression coefficient of the final score on the initial score a = r12 X (S1 = S2). The adjusted difference score is largely independent of initial values.35 Change in the initial scores would be uncorrelated with the final scores if the ratio of r12 divided by the reliability of the test was substituted in the formula above. Unfortunately, the retest reliability of the ischemic pain scores could not be evaluated, although Caldwell and Smith 7 found high retest reliability. The adjusted scores were used in all statistical analyses. Obtained (raw) scores are presented in Fig 1. Similar statistical analyses were conducted using raw scores, yielding results which were similar to those reported in spite of the confounding of results produced by the first session base-level differences.

236 Hypnotic Analgesia

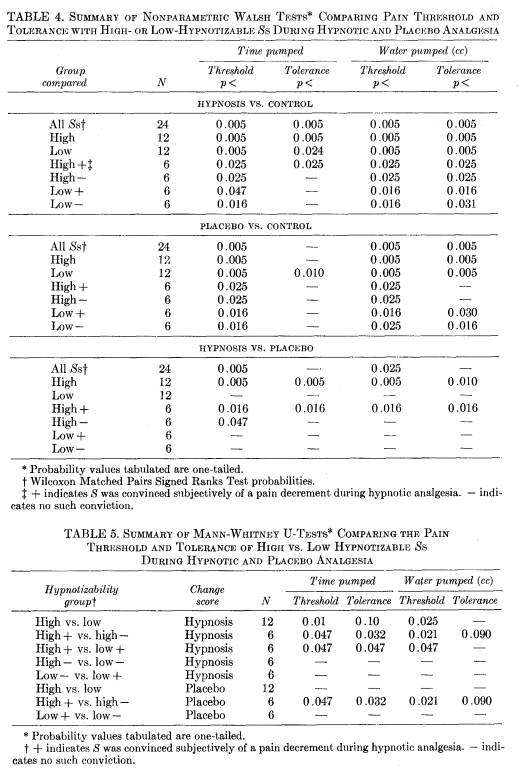

classifications in the replicated-measures design38 were: (A) high or low susceptibility to hypnosis; (B) hypnotic analgesia or placebo. These analyses are summarized in Table 2. (Nonparametric analyses are also summarized in Tables 4 and 5 below.)

Magnitude o f Placebo Response

To what extent was there a reduction in pain following the ingestion of placebo? The increases in threshold for both time and amount of water pumped, 53 and 42%, respectively, are statistically significant (p < 0.001; p < 0.001). The 10% increase in the total time spent pumping is insignificant, but the 15% increase in the amount of water pumped (p < 0.10; Wilcoxon T = 15.5, p < 0.025) indicates that more work was done following placebo, even though pain was not tolerated significantly longer.

Placebo Effect and Susceptibility to Hypnosis

There is no relationship between the magnitude of the placebo effect and susceptibility to hypnosis. The results of the analyses of variance (Table 2), as well as the nonparametric Wilcoxon and Walsh tests (Tables 4 and 5), show that there are no statistically significant differences in the magnitudes of placebo pain relief between high- and low-hypnotizable Ss. This result is important theoretically, and it confirms our hypothesis that susceptibility to hypnosis is not intrinsically correlated with placebo responsivity.10

Hypnotic Analgesia as a Placebo Effect in Low-Hypnotizable Ss

There was a significant increase in performance on all four measures with the insusceptible Ss following the induction of hypnotic analgesia (Table 4 and

237 McGlashan et al.

Fig 1). The pain relief, however, has not been produced by the specific action of hypnosis.

For the insusceptible Ss, the magnitude of the change during the hypnosis session is similar to the magnitude following the ingestion of placebo. For example, for the insusceptible Ss, the adjusted increase in the amount of time pumped until threshold was 63% following placebo and 52% following hypnosis. The differences between hypnotic and placebo analgesia are statistically insignificant for all four measures (Table 2, simple-effects analysis; Table 4). The changes in performance of insusceptible Ss following hypnosis cannot be attributed to hypnosis per se, but appear to represent a reduction in pain due to the placebo effects accompanying the use of hypnosis.

Hypnotic Analgesia in Deeply Hypnotized Ss

The increases in performance (degree of pain relief) following the suggestions of analgesia given to deeply hypnotized Ss are statistically significant (p < 0.005 for each of the four measures, Table 4). To what extent is the effect of hypnotic analgesia in excess of the placebo factors which exist in the hypnotic treatment situation?

To demonstrate a genuine change produced by hypnotic analgesia, it is necessary to show that the change in performance of high-susceptible Ss significantly exceeds the change made by low-sus-

238 Hypnotic Analgesia

ceptible Ss, and that the change made by the deeply hypnotized Ss exceeds their own placebo session performance. Two comparisons, then, are relevant: (1) The change in performance of high-susceptible Ss following hypnotic analgesia is significantly greater than their own placebo changes in Session 3 (p < 0.01 for all four measures; Walsh test, Table 4). (2) The hypnotic analgesia (Session 2) performance of deeply hypnotized Ss is significantly greater than the hypnotic analgesia performance of insusceptible Ss (Tables 2 and 5). The total amount of water pumped does not, however, differ significantly.

These results can be illustrated by the increase in the amount of water pumped to threshold. Deeply hypnotized Ss increased threshold by 63%, compared with their own increase of 41% following placebo analgesia, and compared with the increase for insusceptible Ss of 41% and 44% following hypnotic and placebo analgesia, respectively.

The results indicate that the increase in pain threshold (and similarly in the length of time pain is tolerated) for deeply hypnotized Ss exceeds the already large performance increase which can be attributed to the nonspecific placebo effects of the situation. (The greater pain relief obtained during hypnotic analgesia was limited only to those susceptible Ss who turned out to be more deeply hypnotizable and who were subjectively convinced that they had experienced less pain during hypnosis. This will be elaborated below.)

The true effects of hypnotic analgesia (as well as the placebo effects) were more pronounced with the threshold measures, which may be open to the S's own special interpretation. The effects of hypnotic analgesia, however, also can affect total pain endurance. With the present task, fatigue rather than pain becomes the factor limiting work (cubic centimeters of water pumped). This was apparent with most Ss (both high and low in hypnotizability), as they continued to squeeze the bulb until their muscles would not respond, even though they claimed they could have tolerated more pain. The total work scores demonstrate that both groups pumped to the point of maximum endurance, and displaced an equivalent amount of water in doing so. A comparison of rates of work12 showed that highly susceptible Ss pumped significantly less water per squeeze of the rubber bulb than low-susceptible Ss (17.27 and 18.40 cu cm per squeeze, t = 1.96, p < 0.10). Although both groups pumped an equivalent amount of water, highly susceptible Ss took longer to reach this point: Any large differential effect was prevented when a physiological limit was super-imposed on the task. We interpret this to mean that, under hypnotic analgesia, highly susceptible Ss could tolerate a comparable pain experience for a greater period of time, even though they did not do more work.

Objective Scores and Subjective Pain Ratings

The results demonstrate that hypnotic analgesia does add a potential for pain relief for susceptible Ss over that produced by the placebo factors of the situation. We have not yet shown, however, whether this potential involves mechanisms different from these nonspecific factors.

If hypnotic analgesia per se induces a cognitive change in pain perception, then this effect should be reflected in the subjective ratings of pain reported by Ss during hypnosis. What is more, there should be a relationship between subjective ratings of pain decrement and objective performance increments.

Subjective Pain and Hypnotic Susceptibility During Hypnosis and Placebo

Following each trial, Ss rated the intensity of pain experienced on a 10-point

239 McGlashan et al.

scale. The rank order correlation between Ss' ratings of decreased pain intensity during hypnosis and placebo conditions (compared to the base-level session) was 0.30 (insignificant). For insusceptible Ss, however, the correlation was significant (r = 0.76; p < 0.01). This supports the hypothesis that insusceptible Ss were reacting to similar nonspecific, placebo variables in each session. The correlation for highly susceptible Ss, on the other hand, was insignificant (r = 0.06). The correlations between hypnotic and placebo analgesia for high- and low-susceptible Ss differ significantly (p < 0.001). This supports the hypothesis that deeply hypnotized Ss were responding in different ways in the two sessions. Following suggestions of hypnotic analgesia, the deeply hypnotized Ss were responding in part to variables distinct from situational or placebo factors. The cognitive distortion produced by hypnotic analgesia in highly susceptible Ss is unique to hypnosis and is unrelated to the effects of nonspecific placebo factors accompanying the hypnosis procedure.

Subjective Pain Following Hypnotic Analgesia

In the first control session, 18 of the 24 Ss rated the pain between 8 and 9.5. No S rated 10, as Ss usually stated that muscular fatigue rather than pain prevented them from continuing.

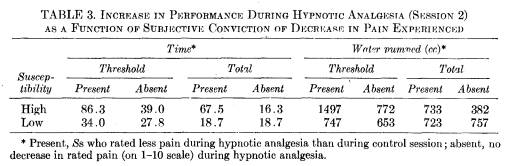

As expected, several deeply hypnotized Ss rated the pain as much less intense following hypnotic analgesia. (This occurred in spite of the increased time they continued pumping.) Unexpectedly, several Ss in the highly susceptible group rated the pain as being the same, or even greater, during hypnotic analgesia compared to the previous control session, in spite of the suggestions of analgesia. Consequently, there happened to be two subgroups with 6 susceptible Ss in each: those who were subjectively "convinced" that the analgesia suggestions had been effective (high+ Ss) and those otherwise susceptible Ss who were "unconvinced" that hypnotic analgesia changed the intensity of the pain (high- Ss). The high+ Ss rated the pain following hypnosis as less intense by a mean of 5.83 points on the 10-point scale; the high- Ss rated a mean increase in pain intensity during hypnosis of 0.58 points.

Since a concerted effort had been made to convince even the insusceptible Ss that potentially they could experience hypnotic analgesia, some insusceptible Ss also reported they felt less pain during hypnosis. The change in pain ratings for the 6 insusceptible Ss who rated the pain as less intense during hypnosis (low+ Ss) was only 1.21 points (using the same cutting point of greater than zero change), significantly below the mean change of 5.83 of the "convinced" susceptible Ss (p < 0.001). The mean increase in pain experience of the "unconvinced" insusceptible Ss (low- Ss) of 1.13 points does not differ from the rating increase of 0.58 of the "unconvinced" susceptible Ss.

These four subgroups have been used in the following data analysis. The distinction between "+" and "-" groups within each susceptibility level is one of convenience, particularly with insusceptible Ss. The changes in the subjective pain ratings following hypnosis are dramatically different, in absolute terms, for those high-hypnotizable Ss (compared to insusceptible Ss) that we have arbitrarily labeled as "convinced." In fact, the differences between the magnitudes of the rating changes for high-, low+, and low- subgroups are statistically insignificant. The latter three groups had essentially the same experience following hypnotic analgesia: The pain felt about the same as it had during the control session. The numerical differences in the rating changes are, however, less important than the fact that

240 Hypnotic Analgesia

meaningful subgroups can be distinguished.

In a clinical setting, probably only the Ss who were convinced subjectively that the analgesia worked would be considered hypnotized. Regardless of previously determined susceptibility, high- Ss, who did not experience analgesia, would not be considered together with the high+ Ss. For this reason, as Barber3 has cogently pointed out, it is tautological to define hypnosis by the S's ability to respond and, then, to argue that he responds because he is hypnotized. It is our view, however, that it is essential to define hypnosis in terms of the S's response to the suggestions given in order to study their effects. The S's responses are, of course, often subjective, and as we have defined analgesia as a subjective decrease in the experience of pain, it is appropriate to use these data as the basis for evaluating objective performance. The division of Ss into "responsive" and "unresponsive" Ss on the basis of their subjective experiences is crucial to understanding the S's objective performance changes in this study as well as in other investigations.*

Objective Performance and Conviction During Hypnotic Analgesia

Objective changes in the length of time spent pumping and amount of water pumped during hypnotic analgesia for the four subgroups (high- and low-susceptible Ss divided on the basis of their subjective conviction about the effectiveness of their own hypnotic analgesia) are summarized in Table 3. Nonparametric statistical analyses are summarized in Tables 4 and 5.

There was no difference in objective performance on the pain task between low+, low-, and high- hypnosis subgroups. The reports by all insusceptible Ss, and by unconvinced susceptible Ss, about whether they felt less pain during hypnotic analgesia showed no relationship to the length of time or to the amount of water pumped. The subjective pain ratings do not necessarily reflect the individual's performance. In this experimental situation, some deeply hypnotizable Ss respond in the same fashion to hypnotic analgesia as do insusceptible Ss. Their response is also similar to the response of the remaining highly susceptible Ss, and all the insusceptible Ss during the placebo session. The high-, low+, and low- Ss can be distinguished neither on the basis of subjective pain ratings nor changes in performance.

In contrast, the performance of the deeply hypnotized Ss who reported that they experienced less pain under hypnotic analgesia was significantly better than the remaining three subgroups. For example, the high+ Ss pumped 67 sec longer with hypnotic analgesia compared to control performance, but the high-,

241 McGlashan et al.

242 Hypnotic Analgesia

low+, and low- Ss increased only 16, 19, and 19 sec, respectively.

The magnitude of the relationship between the changes in the subjective perception of pain and the objective measures of pain reduction may be indicated by the correlations between these measures. For the 12 highly susceptible Ss, the change in subjective pain ratings following hypnotic analgesia correlated 0.50 (p < 0.05) and 0.54 (p < 0.05) with changes in time and cubic centimeters of water pumped to threshold, and 0.65 (p < 0.025) and 0.64 (p < 0.025) with changes in total time and total cubic centimeters of water pumped. The corresponding correlations for the 12 insusceptible Ss were -0.07, -0.06, -0.08, and -0.11.

There are two possible explanations of these findings. First, high Ss may be able to estimate their objective performance, rating subjective pain accordingly. This does not seem likely, because in the postexperimental inquiry, they could not give accurate estimates of performance when asked. Alternatively, the change in performance under hypnosis represents an actual alteration in the cognitive perception of pain.

Conviction, Altered Pain Perception, and Depth of Hypnosis

All highly susceptible Ss had been capable previously of entering deep hypnosis and were selected because of their ability in the clinical trial to experience a positive analgesia. The high+ subgroup, however, obtained higher SHSS:C scores than the high- subgroup (11.17 vs. 9.33; p < 0.01). Similarly, in the diagnostic ratings, 4 out of 6 high+ Ss scored 5 or 5+, while of the highs without subjective conviction, 4 of 6 scored 5-. Even though all high-hypnotic Ss were selected from the upper 5% of the range of hypnotic depth, finer distinctions may need to be drawn in future research. It appears that only a small number of the best hypnotic Ss are capable of experiencing this kind of cognitive pain reduction in an experimental setting. Hypnotic analgesia is quantitatively and qualitatively different from the placebo response for those deeply hypnotized Ss who had the experience that hypnotic analgesia worked for them.

Discussion

With some deeply hypnotized Ss, pain was tolerated longer during hypnotic analgesia than in other contexts in which unspecified situationally determined factors were sufficient to induce significantly increased pain tolerance. Thus, some deeply hypnotized Ss experienced less pain following hypnotic analgesia than they later experienced with placebo medication. These deeply hypnotized Ss also experienced less pain than the significant relief obtained during hypnotic analgesia by insusceptible Ss who were presumably responding to the placebo-like qualities of the hypnotic situation. Even after due allowance was made for the nonspecific placebo effects of the hypnotic session, a residual pain relief effect could be demonstrated following hypnotic analgesia with those highly susceptible Ss who were convinced that hypnotic analgesia had been effective for them.

In this experimental investigation, the pain relief obtained with placebo for threshold and tolerance of about 52% and 15%, respectively, is consistent with previous clinical reports of placebo-induced pain relief.4 Two aspects of the design contributed to the magnitude of the experimentally induced pain relief: (1) Insusceptible Ss were not just reassured that they were good Ss for the purposes of the experiment: A special demonstration was made in order to convince them they could experience hypnotic analgesia. (2) The placebo session was a highly motivating active control procedure, as efforts were made to legitimize the use of placebo in order to maximize

243 McGlashan et al.

response. This was achieved by assuring Ss that the "drug" was a necessary control procedure against which to compare hypnotic analgesia. It was conducted capitalizing on the advantages of the usual double-blind procedure, even though no active drug was used.

This study has demonstrated that hypnotic analgesia objectively increased the pain tolerance of those deeply hypnotized Ss who were simultaneously convinced that they experienced less pain. It is not possible to specify the mechanisms involved in the alteration of pain perception achieved by some of the deeply hypnotized Ss. A variety of negative hallucinations involving most sensory modalities can be induced with deeply hypnotized Ss, and it is plausible that the somesthetic sensation of pain can be subjected to the same kind of cognitive changes as those involved in other negative hallucinations. A number of less compelling alternative explanations could be advanced. Evidence will be presented in subsequent reports demonstrating that changes in anxiety, and several personality and psychological variables that are often associated with pain alleviation, did not differentiate between the performance of susceptible and insusceptible Ss during the three sessions. The effects of hypnosis have been explained in terms of an increased motivation to comply with the wishes of the hypnotist. In general, several reviews have concluded that current evidence does not support such an approach to understanding hypnotic phenomena.11, 22,27

More specifically, the behavior of some of the deeply hypnotized Ss was inconsistent with any explanation in terms of compliance. Only those deeply hypnotized Ss who reported a subjective decrease in pain intensity with hypnotic analgesia showed pain tolerance greater than could be accounted for by the placebo effects of hypnosis. Some Ss who were susceptible to hypnosis, but who did not subjectively experience pain relief with hypnotic analgesia, performed in a similar manner to the unhypnotizable Ss. In other words, Ss who cannot respond to the particular suggestion of analgesia yielded essentially the same kind of results regardless of how capable they are of responding to other kinds of hypnotic suggestion.

There are several implications of our finding that even insusceptible Ss could be convinced that they were capable of responding to hypnotically induced analgesia. Under the present circumstances, some insusceptible Ss subsequently rated themselves as having responded to the analgesia suggestion. The magnitude of the effect was small relative to the highly susceptible Ss, and, unlike susceptible Ss, the insusceptible Ss' subjective ratings did not reflect a corresponding change in objective performance. This finding may help to explain the paradoxical reports that about 60% of unselected Ss respond successfully to glove anesthesia items on several standardized scales of hypnosis 15, 36 even though only very few Ss are able to experience analgesia as a distortion of the primary pain sensation. Glove anesthesia typically is tested with a mild stimulus which tends to be ambiguous. Therefore, the subjective report of glove anesthesia need not reflect a true perceptual distortion, any more than does the pain relief experienced by insusceptible Ss in this study who were convinced hypnosis might work for them.

This result also helps explain the clinical observation that the majority of patients benefit from hypnotic suggestion when it is used in dentistry and with relatively minor surgical procedures. If the S believes in the efficacy of the procedure, hypnotically induced analgesia is effective regardless of the patient's ability to enter hypnosis. The same level of response should be obtained by using a placebo in an atmosphere conveying a similar firm conviction or implicit sugges-

244 Hypnotic Analgesia

tion that it will be effective in suppressing pain. The relationship between the degree of analgesia produced by a placebo and the effect of hypnotic suggestion was similar in this study for the unhypnotizable individuals. Not only is the average performance essentially of the same magnitude, but the correlation of 0.76 between the insusceptible Ss' subjective ratings of pain intensity in both hypnotic and placebo sessions suggests that the pain-reducing mechanisms are similar in both situations -- presumably operating at the secondary level of pain perception. The induction of hypnosis, like the administration of a drug, had strong placebo effects. For very deeply hypnotized Ss, however, suggestions of analgesia reduce pain in a manner that is quantitatively and qualitatively different from a placebo response.

Summary

The effects of hypnotically induced analgesia and placebo response to a "powerful analgesic drug" were evaluated. Highly motivated Ss who were known to be either very susceptible (N = 12) or relatively insusceptible (N = 12) to hypnosis performed a task which induced ischemic muscle pain.

Special procedures were adopted to establish plausible expectations in both groups that the two treatments could effectively reduce pain. An attempt was made to convince insusceptible Ss that they would be able to experience hypnotic analgesia. All Ss were told that the "pain-killing drug" which they ingested would produce the maximum pain relief possible so that the effects of hypnotic analgesia could be evaluated meaningfully. Although all Ss received placebo, the E believed that half of them had received an active drug under the usual double-blind conditions.

Changes in pain threshold and tolerance following hypnotic and placebo analgesia (compared to an initial base-level performance) were evaluated and were related to changes in the S's subjective ratings of pain intensity. Pain reduction was similar for susceptible Ss following placebo and for insusceptible Ss following both hypnosis and placebo. Pain relief exceeding that produced by the placebo response occurred during hypnotic analgesia only for those highly susceptible Ss who subjectively rated the pain as significantly decreased during hypnotic analgesia. The correlation between the subjective pain ratings following the hypnosis and placebo conditions was high for insusceptible Ss but insignificant for susceptible Ss. The correlation between the pain ratings and objective performance during hypnosis, however, was high for susceptible Ss, but insignificant for insusceptible Ss.

The results support the hypothesis that there are two components involved in hypnotic analgesia. One component can be accounted for by the nonspecific or placebo effects of using hypnosis as a method of treatment; the other may be conceptualized as a distortion of perception specifically induced during deep hypnosis.

F. J. E.

l11 North 49th St

Philadelphia, Pa 19139

References

1. BARBER, T. X. Toward a theory of pain: relief of chronic pain by prefrontal leucotomy, opiates, placebos, and hypnosis. Psychol Bull 56:430, 1959.

2. BARBER, T. X. The effects of "hypnosis" on pain: a critical review of experimental and clinical findings. Psychosom Med 25:303, 1963.

3. BARBER, T. X. Experimental analyses of "hypnotic'' behavior: a review of recent empirical evidence. J Abnorm Psychol 70:132, 1965.

4. BEECHER, H.K. Measurement of Sub-

245 McGlashan et al.

jective Responses: Quantitative Effects of Drugs. Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 1959.

5. BEECHER, H. K. The placebo effect and sound planning in surgery. Surgery 114:507, 1962.

6. BROWN, E. E. Evaluation of a new capillary resistometer: the petechiometer. J Lab Clin Med 34:1714, 1949.

7. CALDWELL, L. S., and SMITH, R. P. Pain and endurance of isometric muscle contractions. J Engin Psychol 5:25, 1966.

8. DORPAT, T. L., and HOLMES, T. H. Mechanisms of skeletal muscle pain and fatigue. Arch Neurol Psychiat 74: 628, 1955.

9. ESDAILE, J. Mesmerism in India and Its Practical Application in Surgery and Medicine. London, 1846. Reissued as: Hypnosis in Medicine and Surgery. Julian Press, New York, 1957.

10. EVANS, F. J. Suggestibility in the normal waking state. Psychol Bull 67:114, 1967.

11. EVANS, F. J. Recent trends in experimental hypnosis. Behav Sci 13:477, 1968.

12. EVANS, F. J., and McGLASHAN, T. H. Work and effort during pain. Percept Mot Skills 25:794, 1967.

13. GLIEDMAN, L. H., NASH, E. H., IMBER, S. D., STONE, A. R., and FRANK, J. D. Reduction of symptoms by pharmacologically inert substances and by shortterm psychotherapy. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiat 79:345, 1958.

14. HILGARD, E. R. A quantitative study of pain and its reduction through hypnotic suggestion. Proc Nat Acad Sci 57:1581, 1967.

15. HILGARD, E. R., LAUER, L. W., and MORGAN, A. H. Manual for Stanford Profile Scales o f Hypnotic Susceptibility: Forms I and II. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, Calif, 1963.

16. HILL, H. E., KORNETSKY, C. H., FLANARY, H. G., and WIKLER, A. Studies on anxiety associated with anticipation of pain. I. Effects of morphine. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiat 67:612, 1952.

17. HONIGFELD, G. Non-specific factors in treatment. I. Review of placebo reactions and placebo reactors. Dis New Sys 25:145, 1964.

18. LASAGNA, L. The clinical evaluation of morphine and its substitutes as analgesics. Pharmacol Rev 16:47, 1964.

19. LEPANTO, R., MORONEY, W., and ZEN HAUSERN, R. The contribution of anxiety to the laboratory investigation of pain. Psychon Sci 3:475, 1965.

20. LEWIS, T. Pain. Macmillan, New York, 1942.

21. LIBERMAN, R. An experimental study of the placebo response under three different situations of pain. J Psychiat Res 2:233, 1964.

22. LONDON, P., and FUHRER, M. Hypnosis, motivation, and performance. J Personality 29:321, 1961.

23. MARMER, M. J. Hypnosis in Anesthesiology. Thomas, Springfield, Ill, 1959.

24. MEARES, A. A System of Medical Hypnosis. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1960.

25. NISBETT, R. E., and SCHACHTER, S. Cognitive manipulation of pain. J Exp Soc Psychol 2:227, 1966.

26. ORNE, M. T. The nature of hypnosis: artifact and essence. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 58:277, 1959.

27. ORNE, M. T. Hypnosis, motivation and compliance. Amer J Psychiat 122:721, 1966.

28. ORNE, M. T., and O'CONNELL, D. N. Diagnostic ratings of hypnotizability. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 15:125, 1967.

29. SHAPIRO, A. K. Factors contributing to the placebo effect: their implications for psychotherapy. Amer J Psychother 18:73, 1964.

30. SHOR, R. E. "On the Physiological Effects of Painful Stimulation During Hypnotic Analgesia: Basic Issues for Further Research." In Hypnosis: Current Problems, Estabrooks, G. H., Ed. Harper, New York, 1962, p. 54.

31. SHOR, R. E. Physiological effects of painful stimulation during hypnotic analgesia under conditions designed to minimize anxiety. Int J Clin Exp Hypn 10:183, 1962.

32. SHOR, R. E., and ORNE, E. C. The Harvard Group Scale of Hypnotic Susceptibility, Form A. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, Calif, 1962.

33. STERNBACH, R. A. Pain: A Psycho-

246 Hypnotic Analgesia

physiological Analysis. Acad. Press, New York, 1968.

34. SUTCLIFFE, J. P. "Credulous" and "skeptical" views of hypnotic phenomena: experiments on esthesia, hallucination, and delusion. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 62:189, 1961.

35. TUCKER, L. R., DAMARIN, F., and MESSICK, S. A base-free measure of change. Psychometrika 31:457, 1966.

36. WEITZENHOFFER, A. M. Hypnotism: An Objective Study in Suggestibility. Wiley, New York, 1953.

37. WEITZENHOFFER, A. M., and HILGARD, E. R. Stanford Hypnotic Susceptibility Scale, Form C. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto, Calif, 1962.

38. WINER, B. J. Statistical Principles in Experimental Design. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1962.