The Institute of Pennsylvania Hospital, and University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19139

The dramatic pain suppressant effect of hypnoanesthesia has for a long time been a source of fascination and controversy. Surgical procedures ranging from appendectomies to thyroidectomies and from cesarean sections to open heart surgery have been carried out with hypnosis as the sole anesthetic, providing impressive and tangible evidence of the effectiveness that psychological factors can have in suppressing pain. Although it cannot be doubted that these procedures have been carried out with hypnosis, the interpretation of this fact remains a source of controversy.

In this chapter we shall seek to clarify questions about the reality of hypnoanesthesia, to juxtapose clinical evidence with laboratory data, and to address the apparent paradox that although over 90% of the population shows an increase of pain threshold with appropriate hypnotic suggestions, only a small percentage of unselected subjects can enter deep hypnosis. Finally, an effort will be made to suggest that two different kinds of psychological mechanisms are likely to be involved in the production of hypnotically induced analgesia.

REALITY OF HYPNOANESTHESIA

The induction of hypnosis is a remarkably simple procedure. The patient is instructed to focus his attention, to think about his eyes growing heavy, and to drift off as if to sleep. Typically the procedure takes only a few minutes. No drug is given and nothing dramatic is done to the patient. Nonetheless, moments later a suitable individual responds to suggestions that his body is becoming insensitive to pain, and as these suggestions are continued, it becomes possible to carry out surgical procedures.

This course of events is startling to the modern observer, not because surgery can be carried out on a relaxed and comfortable patient (a great many anesthetics allow this to occur) nor even because the patient is awake and comfortable (either local or regional anesthetics permit such a course of events) but rather because there is no obvious mechanism to account for the suppression of pain. The problem is further complicated by the absence of clear-cut physiological changes associated with entering hyp-

717

718 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

nosis. Although suggestions of drowsiness may cause the patient to look like he is asleep, he continues to respond to the hypnotist's voice, shows no unique changes in the EEG, and is able to perform complex cognitive tasks without difficulty. Given appropriate suggestions, the patient may show every evidence of being wide awake, but nonetheless he will assert that he feels no discomfort even as major surgery is being carried out. The idea that a psychological process, occurring relatively quickly and easily in normal individuals and unaccompanied by unique physiological changes, can cause such profound alterations in an individual's response to obviously painful stimuli seems to fly against common sense expectations. It is hardly surprising that some observers are loath to accept the patient's assertion that he feels no pain under these circumstances.

Although the patient is for the most part relaxed during surgery, careful observation reveals that as the surgeon pulls on the peritoneum or manipulates some other organ richly endowed with pain receptors, changes in both heart rate and respiratory patterns can be seen to occur, at times associated with facial grimaces that might suggest pain. Not only is it possible to observe such changes in the naturalistic setting of the operating room, but in carefully controlled laboratory studies the subject who is in deep hypnosis and reports total insensibility to pain nevertheless shows the kinds of changes in heart rate and galvanic skin response (GSR) usually associated with pain stimuli (6).

These inconsistencies in the hypnotic response have long confused investigators and have raised serious questions in the minds of some observers about the reality of hypnotically induced anesthesia. Thus one way in which the phenomenon has been explained is to contend that the hypnotized patient is so eager to please the hypnotist or is so anxious to maintain the role of being a hypnotized subject or has some other personal -- or even ulterior -- motive that he is willing to bear the pain and make believe that he is comfortable. Much in the way the Greek stoics or the American Indians placed great emphasis on a brave man's ability to bear pain without outward signs of suffering, so, the argument goes, does the hypnotized subject strive to control both the external appearance of pain and his verbal reports. Only the physiological response and his occasional inability to suppress a facial grimace reveals his suffering.

The physiological data clearly indicate that pain perception must take place at least at the level of the thalamus, whereas other evidence to be discussed shows that pain perception also occurs at the cortical level.

Several investigators (1,3,4) have observed that when painful stimuli are applied to a hypnotically anesthetized limb a deeply hypnotized subject will assert verbally that he feels no pain, but at the same time he may indicate by means of automatic writing his appreciation of pain at another level. Automatic writing is a phenomenon relatively easily induced by giving a deeply hypnotized subject a pencil and the suggestion that the

719 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

pencil will begin to write without his awareness of what is being written or, for that matter, that writing is occurring at all. Most interestingly, if the subject is asked to examine the material he has produced he will often disown it and insist that the ideas and sentiments expressed are not his own. Automatic writing is one of the procedures used by Morton Prince in his classic studies of coconsciousness, and there is a not inconsiderable body of poetry and mystical literature produced by means of automatic writing which, once learned, can also be carried out in the waking state. The best known example of such poetry is in the work of Gertrude Stein.

Recently Hilgard (2) has extended his systematic studies of hypnoanalgesia using a technique of automatic speaking. In addition to the usual kinds of verbal pain reports which are obtained while the subject is exposed to ischemic muscle pain, he instructs his deeply hypnotized subject that when he places his hand on the subject's right shoulder, that part of him which is not normally responsive but aware of all aspects of his experience will provide its own verbal pain report. When the subject is asserting that he feels no pain, Hilgard obtains pain ratings from what he terms the "hidden observer," which clearly indicates a considerable degree of pain at another level of awareness. Interestingly, however, these reports are given without the affect of suffering which would otherwise accompany them. Thus, although the deeply hypnotized subject reports experiencing no pain, the "hidden observer" typically reports awareness of some pain, but characteristically less than one would expect from the same subject exposed to the same stimulus in the waking state.

These data indicate that pain is perceived at a cortical level but not that the individual is merely suppressing his suffering. Thus patients who have had surgery under hypnoanesthesia continue to assert the effectiveness of the suggested pain relief long after surgery; even when pressed by skeptical friends, they continue to insist postoperatively that they did not in fact endure any suffering. These patients also require little if any postoperative analgesia, a behavior that is often markedly different from that which the same patients exhibited after prior surgery. When hypnoanalgesia is used in other contexts such as the treatment of intractable pain, as in terminal cancer, the need for narcotics is rapidly reduced and usually eliminated. In each of these instances one can still argue that the patient is somehow trying to please the hypnotist, but in many instances even such an implausible argument cannot be maintained. For example, one woman who had delivered a child with hypnoanesthesia moved to another city and went to great trouble to seek another obstetrician who used this technique. If she had really suffered discomfort and merely inhibited its expression during the original delivery, it is difficult to understand why she would choose to go through such a charade yet another time.

In a laboratory context analogous evidence can be cited. Typically, subjects participating in pain experiments will assert not only to the investi-

720 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

gator himself but also to their friends away from the laboratory that they experienced no discomfort in the hypnoanalgesic condition. Not infrequently a subject who has taken part in such a study, when asked if he would be willing to participate in a similar experiment in the future, indicates that he is quite prepared to repeat the hypnoanalgesia segment but under no circumstances would he repeat the waking control part of the study, which involved his having to experience the same pain stimuli without hypnosis. Although it is difficult to prove that subjects are not willfully lying when they describe their experience during hypnoanalgesia, such an explanation is extremely implausible, and no proponents of such a view have been able to persuade volunteers to undergo major surgery without any form of anesthesia.

The absence of objective measures of pain needs to be recognized as a serious problem in all pain research, and indeed studies of hypnotically induced analgesia have been particularly sensitive to the problems of the validity of subjective reports -- issues that need to be addressed in evaluating any reported analgesic effects. Certainly care must be taken to obtain subjects' reports in a context that is most likely to maximize honest reporting. Moreover, although it would be desirable to have an index of pain other than subjective reports, it should be kept in mind that these reports are the only meaningful way of indexing pain, which is after all a subjective experience -- whether or not it is associated with concomitant physiological alterations. From our point of view, neither a physiological response nor a behavioral response can ever be more than an imperfect correlate of pain. The phenomenon itself resides in the patient's subjective experience of suffering, which may be more or less adequately reflected in a particular measure employed in a particular study.

In summing up the phenomenon of hypnotically induced analgesia, it seems clear that some deeply hypnotized subjects are able to tolerate surgical pain and analogous painful stimuli in the laboratory while asserting that they feel no discomfort. With appropriate techniques these subjects report an awareness of pain at another level without, however, evidence of suffering. The patient who asserts that he feels no pain seems to be truthful in asserting what he is actually experiencing, even though at some cortical level pain is perceived. However, the mechanisms by which hypnoanalgesic effects can be explained remain to be elucidated.

NATURE OF HYPNOTICALLY INDUCED ANALGESIA

It is well known that psychological factors affect pain perception. Consider, for example, the athlete who sustains a fracture but continues until the game is completed without even becoming aware of an injury that normally would cause exquisite pain; the dental patient who suffers intensely and on reaching the dental chair is no longer aware of his pain;

721 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

the patient who obtains profound relief from an injection of saline; and so on. There is a tendency to group all psychological mechanisms together, assuming somehow that they are similar or even the same. Particularly the placebo effect is generally conceived of as a form of suggestion closely related to hypnosis.

Because it is not possible to review here the voluminous literature on hypnotic analgesia, we will limit ourselves to research in our laboratory which addresses the particular relationship between hypnotic analgesia and the placebo effect (5). First, we sought to compare the effect of hypnotically induced analgesia with the effect of placebo. Second, we wished to study the effect of suggestions of analgesia on highly hypnotizable subjects as opposed to unhypnotizable subjects. An elaborate experimental design was developed to control for experimenter bias and similar problems in research by employing two groups of subjects, one that was highly hypnotizable and the other unable to respond to hypnosis. A hypnotic induction procedure is employed where there is no test of response to hypnotic suggestion that would result in a different response in these two groups of subjects. The two groups are treated in the identical manner by an investigator who is unaware of the subjects' past experience with hypnosis. These conditions make the procedure closely analogous to the double-blind technique used in psychopharmacology.

This approach takes advantage of the fact that the ability to enter hypnosis is a remarkably stable attribute of the individual. After three sessions the correlation between two succeeding standardized measures of hypnotizability is in excess of 0.9. It is therefore feasible to test subjects several times, selecting the two groups to be compared from the two ends of the distribution: those who are consistently highly responsive and those who are consistently unresponsive over repeated sessions. Since one group is essentially unresponsive to hypnotic suggestions, any effects observed in that group cannot be ascribed to hypnosis. At the same time, both groups will try to follow instructions to the best of their ability and be responsive to verbal and nonverbal cues indicating how they should behave. The one problem with this control group is that unhypnotizable subjects will have failed to respond in several experiences, and although it is possible to keep the hypnotist blind as to their status, they themselves will be aware that they are in essence unresponsive. Consequently, these subjects may well perceive the demands of the experimental situation quite differently. To solve this subtle but crucial problem in the design, we modified the procedure by including a special session designed to convince the unhypnotizable group that they could actually respond to hypnotic suggestions sufficiently well for the purposes of the study.

Another hypnotic session was arranged for the unhypnotizable subjects with a different hypnotist who employed a technique based exclusively on relaxation. Great care was taken not to test the ability of these subjects

722 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

to respond to hypnotic suggestions and thereby avoid providing feedback that would indicate to them their continuing inability to respond. The subjects were treated as though they were responding extremely well to the particular procedure being employed. Even unhypnotizable individuals reach a state of profound relaxation under these circumstances. Once this had occurred, the hypnotist began to suggest analgesia of the right hand, again taking great care to induce the suggestion slowly and deliberately.

The analgesia suggestion was tested with electric shocks from an inductorium, and each subject was asked to compare the intensity of the shock in the analgesic hand with that in the normal hand. Although these subjects had been unhypnotizable, all of them experienced a considerable degree of analgesia because (unknown to them) the setting of the transformer was altered appropriately -- they actually received less shock to the hand where analgesia had been suggested than to the normal hand. This manipulation was done carefully and within plausible limits. As a consequence, these subjects expressed considerable fascination and pleasure with the success of the analgesia suggestion. Careful postexperimental discussion supported the behavioral observations that these individuals were indeed persuaded about their ability to respond to analgesia suggestions. One subject who still doubted his responsiveness was excluded from participation.

This unusual manipulation resulted in a group of subjects who were essentially unresponsive to hypnosis as established by careful evaluation long before the experiment (and that persisted after the study), but who nonetheless believed themselves to be capable of responding to a particular form of hypnotic induction and to the suggestion of analgesia.

Subjects were then solicited for an experiment involving pain tolerance, and during a base-line session their tolerance for ischemic pain was established. The experimental population consisted of 12 highly hypnotizable and 12 unresponsive subjects. They were required to perform work that was quantified by the length of time pain was tolerated as well as by the amount of water they were able to pump while blood flow was occluded by means of a blood pressure cuff inflated to 200 mm Hg. Subjects were urged to pump as long as they could, and the initial pain threshold (when the sensation in the arm was first noticeably painful) and pain tolerance (when pain was so unbearable that they were unable to continue) were noted.

After the initial base-line session, all subjects returned and were tested by an experimenter who was not familiar with their previous hypnotic experiences in a session where a relaxation method of hypnotic induction was employed and analgesia was induced in one arm. The same technique of assessing pain threshold and tolerance that was used during the first session to test hypnotically induced analgesia was employed.

723 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

All subjects were asked to return for yet a third session. It was explained to them that during this session a drug would be used to help establish how effective hypnotic analgesia really was. It was pointed out that a powerful new analgesic drug was being employed that was known to suppress ischemic muscle pain. It was implied that the drug would work well and that this would allow us to see how closely hypnotic analgesia could approximate the drug effect. The experimenter himself believed he was administering dextropropoxyphene (Darvon ®) and placebo in a double-blind manner. The pharmacy, however, had delivered two bottles, both of which were placebo: one had been labeled Darvon ® and one placebo. The secretary then made up the usual envelopes from these bottles. Since no one in the laboratory other than myself was aware that there was no active drug, we created a firm belief in the experimenter that he was carrying out a drug study. However, all subjects received placebo, making the entire sample available for analysis.

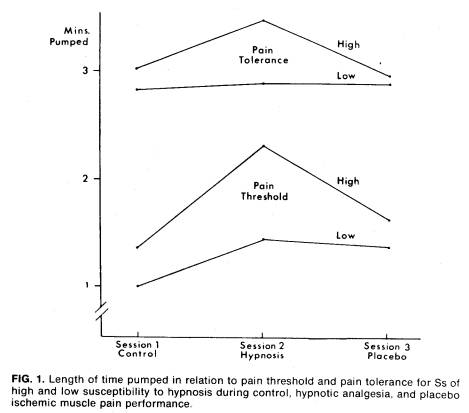

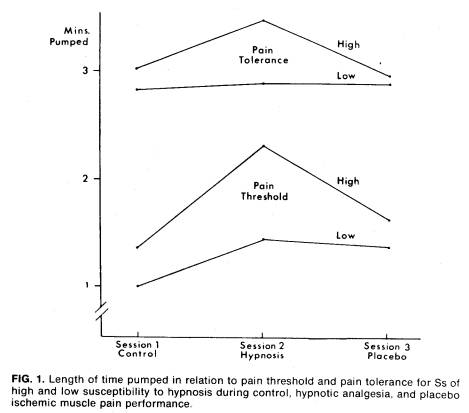

Figure 1 summarizes our findings of the effect on pain threshold: the more sensitive, albeit less reliable, measure of analgesic response clearly

724 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

shows that both groups responded to the hypnotic induction procedure. Although the pain threshold of the highly hypnotizable group is raised considerably more than that of the insusceptible group, the increment in pain threshold of the insusceptible group is nonetheless significant. In contrast, the change in pain threshold to placebo is identical in the groups. The pain tolerance findings show little change in the nonhypnotizable as opposed to a dramatic change in the hypnotizable group in response to posthypnotic suggestion.

The relationship between the response to hypnosis and the response to placebo is particularly interesting. Contrary to what is generally believed, there was no difference in the placebo response between the highly hypnotizable subjects and those who were insusceptible. On the other hand, the relationships between the placebo response and the effect of hypnotic analgesia were very different in these two groups. Thus in the unhypnotizable subjects the response to hypnotically induced analgesia correlated with the response to placebo 0.76, p < 0.01. In the highly hypnotizable group the correlation was totally insignificant, r = 0.06. These data strongly support our view that if the hypnotic procedure is expected to be effective by the subject it can exert a nonspecific placebo effect on his response to a painful stimulus. Note that the level of response to placebo in unhypnotizable subjects is, on the average, the same as that to hypnosis. The highly responsive subject, on the other hand, derives more benefit from hypnosis than he does from placebo. Moreover, the fact that the amount of relief yielded is uncorrelated with the amount of relief obtained with placebo in this group strongly suggests that two independent mechanisms are involved.

The placebo effect stems from the patient's belief in the drug's effectiveness, and it follows therefore that any other procedure that can evoke analogous patient expectancies will produce pain relief because of the same mechanism. In this sense it is appropriate to speak of a placebo effect of hypnosis that will occur in hypnotizable and unhypnotizable individuals alike, provided they both share the conviction that the procedure will be helpful. We were able to show that the nonspecific effect that is a function of the hypnotic procedure and independent of the patient's response to hypnosis results in a modest but nonetheless highly significant analgesic action. On the other hand, the specific effect of suggestions of hypnotic analgesia in the highly hypnotizable individual will result in a much more profound level of analgesia, which we expect will be additive with the nonspecific placebo component that can occur in all individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

What are the implications of these findings? As we pointed out earlier in this report, 90% of patients are helped by hypnotic analgesia in a dental

725 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

context. However, this means that the patient becomes less anxious, allows the administration of local anesthetics, and is easier to manage. These important benefits do not require profound levels of analgesia but can be achieved by suggested relaxation and the associated analgesia owing to nonspecific placebo components inherent in the procedure. On the other hand, surgical anesthesia, in which the patient is exposed to profound pain stimuli, requires highly responsive hypnotic subjects since in these instances the control of pain involves a phenomenon best conceived of as a negative hallucination for pain. Much research on hypnosis has shown that any kind of negative hallucination, be it visual, auditory, or tactile, is difficult and requires considerable hypnotic skill on the part of the patient. This can be achieved only in a relatively small proportion of the population. Although motivational factors affect this proportion to some degree, 20% seems the likely upper limit.

These findings help explain the clinical observation that hypnosis is helpful in a high proportion of patients. Parenthetically it should be added that direct hypnotic suppression is rarely ever indicated in the treatment of functional pain. Enduring results with functional pain are achieved only when the contingencies associated with the symptom are fully understood and appropriately dealt with. On the other hand, hypnosis is ideally useful in helping to ameliorate transient pain induced by the physician or chronic pain of organic origin. Even the unhypnotizable subject will benefit from the hypnotic procedure because of its placebo component, and it may serve to renew hope, to reengage the patient in meaningful activities and thus decrease his somatic preoccupation, thereby greatly facilitating his functioning. Further, if the patient happens to belong to the approximately 20% of the population who have the skill of experiencing profound hypnotic phenomena, there is a good likelihood of almost complete relief owing to the specific effect of hypnotic suggestion on the hypnotizable individual. Since hypnosis in the treatment of organic pain is uniquely safe, non-habit forming, and easily applied, especially in conjunction with training in self-hypnosis, an appropriate therapeutic trial of this procedure is definitely indicated before considering the invasive or mutilating procedures that have been widely used in an effort to control pain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The substantive research on which this paper is based was supported in part by grant #MH 19156 from the National Institute of Mental Health and in part by the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry.

REFERENCES

l. Estabrooks, G. H. (1957): Hypnotism, Rev. ed., E. P. Dutton & Co., New York.

2. Hilgard, E. R. (1973): Psychol. Rev., 80:396.

726 HYPNOTIC PAIN CONTROL

3. James, W. (1889): Proc. Am. Soc. Psychical Res., 1:548.

4. Kaplan, E. A. (1960): Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 2:567.

5. McGlashan. T. H., Evans, F. J., and Orne, M. T. (1969): Psychosom. Med., 31:227.

6. Shor, R. E. (1962): In: Hypnosis: Current Problems, edited by G. H. Estabrooks, p. 54. Harper & Row. New York.

Figure 1 (p. 723) (from McGlashan, T.H., Evans, F.J., & Orne, M.T. The nature of hypnotic analgesia and placebo response to experimental pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 1969, 31, 227-246.) c 1969 by American Psychosomatic Society, Inc., is reproduced here with the kind permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins c.