As one reviews Jolly West's contributions, his depth and breadth are unique, ranging from brainwashing to sleep deprivation, from cults to psychotherapy, from hallucinations to dissociative reactions. This chapter addresses an issue in which Jolly has had an enduring interest: the heuristic and therapeutic implications of different models of self.

Multiple personality disorder (MPD), once a rare condition, has become almost commonplace today. In 1990 alone, there were far more diagnoses made of MPD than in the 75-year period 1895 to 1970. As the number of patients diagnosed with MPD has increased, so too has the number of therapists specializing in its treatment. Similarly, the amount of published reports concerning dissociation has grown dramatically, and there are now scientific conferences and a specialty journal devoted primarily to issues regarding MPD.

There has also been a fundamental change in the essential nature of this condition, such that practitioners of the last century would have a difficult time recognizing the MPD treated by many contemporary therapists. Although clinicians used to observe two, perhaps three, personalities within a given patient, it is no longer unusual for there to be more than 10 alter personalities, and over 100 have been "discovered" in several cases. Even more troubling is the fact that what was once a relatively benign condition has evolved into one of the more grim mental illnesses of our time. Today's MPD patients tend to be severely disturbed and dangerously unpredictable: nearly half engage in self-mutilation;1 close to 50% are alleged criminals; approximately 13% report committing a homicide; and over 90% have threatened suicide.2

Most clinicians today view these morbid characteristics as inherent to MPD. Because the disorder is presumed to result from early childhood trauma, it is anticipated that dissociated parts of the self will evidence sadistic and masochistic tendencies. It may come as a surprise, then, to learn that MPD was not always such a malignant condition, that there was a time when it was unusual to observe alter personalities that were genuinely destructive. The celebrated case of Miss Beauchamp, treated and reported by Morton Prince early in the century, provides an illustrative example. Although Prince sometimes referred to this patient's personalities as The Saint, The Woman, and The Devil, notice how he described the latter: "Sally is the Devil, not an immoral devil, to be sure, but rather a mischievous imp, one of that kind which we might imagine would take pleasure in thwarting the aspirations of humanity. To her pranks were largely due the moral suffering which BI [Beauchamp] endured. "3 Words like mischievous, imp, and pranks contrast sharply with those typically used to describe the more antisocial alters observed in today's MPD patients. Prince addressed the nature of dissociated personalities even more directly when he wrote:

Miss Beauchamp is an example in actual life of the imaginative creation of Stevenson, only, I am happy

247

248 Orne and Bates

to say, the allegorical representation of the evil side of human nature finds no counterpart in her makeup. The splitting of personality is along intellectual and temperamental, not along ethical lines of cleavage. For although the characters of the personalities widely differ, the variations are along the lines of mood, temperament, and tastes. Each personality is incapable of doing evil to others.3

Prince's remarks concerning Miss Beauchamp are indicative of his experiences with other MPD patients and, indeed, reflect the prevailing attitude of his time. If the patient was usually quiet, melancholy, and morose, the alter personality was typically flamboyant, gay, and excitable; the most troubling qualities observed among alters were likely to be vanity or jealousy.

How are we to understand the transformation that MPD has undergone? What are the driving forces responsible for its metamorphosis? One is left wondering what aspects of the phenomenon are intrinsic to its nature and what features are incidental by-products of the zeitgeist. The problem is strikingly analogous to that faced by hypnosis researchers, who are by now accustomed to wrestling with such questions. Like MPD, hypnosis has been something of a chameleon, surreptitiously changing colors to reflect its surroundings. The behaviors and subjective experiences associated with hypnosis have proven to be supremely malleable, strongly influenced by the expectations and beliefs of both hypnotist and subject.

In fact, hypnosis and MPD share a checkered past, marked by short periods of intense interest, during which outrageous and unsubstantiated claims were frequently made, followed by extended droughts of scientific and clinical attention. Furthermore, it is during hypnosis that alter personalities most often make their initial appearance, and it is with the aid of hypnosis that early practitioners typically endeavored to treat MPD, a clinical regimen still prescribed by many contemporary therapists.4-6 The kinship between these two conditions stems primarily from the fact that the phenomenon of dissociation is central to both. The hypnotic responses that intrigue theorists are those that are experienced as involuntary, for which the behavior itself has become dissociated from volitional intent; MPD can involve dissociated sets of ideas, feelings, and memories. Some investigators, including Bliss, go so far as to define MPD in terms of hypnosis: "The crux of the syndrome of multiple personalities seems to be the patient's unrecognized abuse of self-hypnosis. This unintentional misuse seems to be the primary mechanism of the disorder. "7

Certainly, there is no doubt that MPD and hypnosis share a common core of phenomenological features. Unfortunately, investigation of these features is complicated by the fact that they cannot be studied directly but must be inferred on the basis of patients' reports. It is for this reason primarily that many of the fundamental problems currently facing MPD researchers have parallels within the domain of hypnosis. In light of the many linkages, historical and contemporary, between these two conditions, it is hardly surprising that issues relevant to one may also be pertinent to the other.

The Ephemeral Nature of Dissociative Conditions

Throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Mesmer's patients regularly gathered in his apartment around a baquet filled with iron filings, and would, on his ceremonial entrance, experience seizure-like crises so violent that they frightened onlookers (see also chapter 24). Mesmer believed that these crises resulted from the rearrangement of a magnetic fluid within the body and that they were an inherent feature of animal magnetism. Within Mesmer's lifetime, however, the Marquis de Puysegur demonstrated that patients could remain calm during trance, dispelling the notion that convulsive attacks were necessary. Yet, fantastic as it may sound, Puysegur's patients regularly claimed paranormal powers, including clairvoyance and telepathy, features that Puysegur regarded as essential to trance. Just 100 years later, Jean-Martin Charcot, the great French neurologist, "discovered" that hypnosis constituted a physiological state that had three distinct stages: catalepsy, lethargy,

249 Multiple Personality Disorder

and somnambulism. When Charcot induced hypnosis, it followed a clearly delineated course. For instance, rubbing the top of a subject's head led the subject from lethargy into somnambulism. Despite strong opposition by Bernheim and Liebeault at Nancy, who argued that Charcot's observations were founded on suggestion, Charcot maintained that his patients' behaviors reflected the intrinsic nature of hypnosis.

Each investigator, Mesmer, Puysegur, and Charcot, insisted that his patients' behavior and experiences during trance were intrinsic to the process. Each refused to believe that the behavior subjects manifested on entering trance was a function of their concept of how a hypnotized person should behave. In retrospect, it is clear that each investigator was mistaken. Afforded the luxury of historical perspective, it is difficult to overlook the profound influence exerted by belief and expectation on the hypnotic experiences of each clinician's patients. However, the inability of these observers to recognize this fact should give us pause. Their limited awareness of the extent to which the phenomenon was shaped by the culture and their own preconceptions underscores the insidious manner in which these forces exert their influence.

Consider the following experiment carried out by Orne to investigate the role that shared expectations play in shaping hypnotic behavior.8 Two large classes of students were given a lecture on hypnosis, followed by a brief demonstration involving three individuals. Unknown to either class, the three demonstration subjects had been hypnotized before the presentation and had been given a suggestion that they would experience catalepsy of the dominant hand. Although catalepsy is frequently observed during hypnosis, if it is seen, it generally occurs throughout the body; catalepsy of only one arm had never been described in the literature. The key difference between the exhibitions in each class was that unilateral catalepsy was tested in the three demonstration subjects in only one class. For this class, it was casually pointed out that catalepsy of the dominant hand is typical of deep hypnosis. Within 1 month, students from both classes were randomly selected to undergo hypnosis with an investigator who was unaware of which class they were from. Although half of those exposed to unilateral catalepsy displayed this phenomenon during hypnosis, none of the subjects from the nonexposed class did, illustrating the subtle yet powerful influence that expectancies and beliefs about hypnosis can have on hypnotic behavior and experience.

The Substrate for MPD

Unfortunately, there is less recognition that expectation and belief also have the potential to influence the clinical presentation of psychopathology. In particular with dissociative conditions, our patients' experiences will be influenced by the therapeutic context, existing cultural views, as well as their own and their therapists' prior experiences and expectations. The position taken here is not parallel to that often attributed to Szasz9 -- that mental illness is a myth. Rather, we are suggesting that patients with various psychological and emotional conditions can be guided toward a diagnosis of MPD if they have an ability to dissociate, if they have a tendency to forget their past behaviors, if they have difficulty accepting and owning conflictual feelings, and if they are encouraged to discover remote "memories" and "other selves." The resulting disorder is real, but its manifestations are largely determined by the cultural context in which they occur and the type of therapy received. The focus of this chapter is to clarify some significant aspects of MPD and to consider alternative ways of treating dissociative conditions that attribute responsibility for discordant thoughts and feelings to a single self.

With regard to MPD, it is possible that the dangerous symptomatology currently associated with the disorder, as well as the condition's unfavorable prognosis, is shaped by the attitudes and convictions of those who treat it. Certainly, most individuals with psychological difficulties experience confusion about what they are going through and are receptive to information that will help them make sense out of an otherwise meaningless and frightening stream of events. Before ever obtaining professional

250 Orne and Bates

assistance, our patients have assimilated the prevailing cultural views concerning mental illness. Via television, radio, magazines, advertisements, books, films, and word of mouth, they have already begun to think of themselves, and their emotional difficulties, in ways consistent with societal standards. Today, that means that more and more patients enter therapy prepared, if not already committed, to focus on dissociative features of their daily experiences. Just as many psychoanalytic patients suspect in advance that their neuroses stem from repressed wishes and fears, today's patients frequently begin psychotherapy assuming that their difficulties result from the existence of alter personalities, of which they are not yet aware, that emerged as a result of early childhood trauma, which they do not yet recall.

As therapists, our own views are also influenced by the culture in which we live and practice. If we are interested in working with MPD patients, we keep up to date by reading the most recent theoretical articles on MPD, perhaps even attending workshops given by experts in the field. We are told that MPD is underdiagnosed because clinicians often mistake it for other psychological conditions. We learn about the telltale signs and symptoms of MPD, especially those to watch for when we suspect that a patient suffers from MPD but have not yet been able to confirm the diagnosis. The experts inform us that typical MPD cases display several alter personalities, up to 15 or more, although considerable exploration may be required before some alters are uncovered. Finally, we hear again and again that the disorder is caused by early childhood abuse and that we should carefully and repeatedly discuss this issue with patients, many of whom will not at first remember such experiences. This information shapes the way we think about MPD, as well as the manner in which we treat it.

Once psychotherapy begins, we pass along to our patients the prevailing views regarding MPD. This process can occur in a gradual and subtle fashion, or more immediately and directly, an approach preferred by Bliss:

The first step is to make the subject aware of the problem. Although she has lived in this twilight state for years, experienced amnesias, and been told by others about her strange behaviors, the reality has not been confronted. Under hypnosis, the alter egos are summoned, and usually speak freely. When they appear, the subject is asked to listen. She is then introduced to some of the personalities, with the option to remember the experience when she emerges from hypnosis. 10

Furthermore, our patients are highly motivated to accept the formulations we give them, because the process of labeling and describing a condition implies that the disorder is understood and instills hope that it can be successfully treated. As a therapeutic rationale is gradually imparted, patients come to define themselves in terms of it. Hence, patients of psychoanalysts eventually develop Oedipal conflicts, patients of cognitive-behaviorists predictably evidence cognitive distortions, patients of existential therapists reliably display profound existential anxiety, and so on. In a true sense, the therapist is correct in each of these situations, for there is evidence in the therapeutic material to support each distinct model of treatment. In this same way, MPD patients of therapists who possess strong views regarding the incidence, cause, and treatment of this condition will gradually come to confirm their therapists' expectations -- not because they are involved in a ruse, but because doing so offers reassurance that the diagnosis and formulation are correct and hope that treatment will lead to a cure.

Multiple Personality Disorder and Self-Mutilation

The chronological history of the relation between MPD and self-mutilation may provide a contemporary example of how mutually shared expectations can shape the clinical presentation of psychopathology. On the basis of various case histories, we know that self-mutilative behaviors were rarely exhibited by MPD patients treated a century ago. In the first modern investigation, Bliss10 reported that 21% of MPD patients engaged in self-mutilation; two subsequent studies11,12 found an incidence rate of 34%; most recently, Coons and Milstein1 reported that self-mutilation occurred in 48% of individuals diagnosed with MPD. Since the original observation was announced just 10 years ago, the incidence rate of self-mutilative

251 Multiple Personality Disorder

behaviors among MPD patients has more than doubled! Why? Perhaps the lead paragraph in the discussion section of the Coons and Milstein 1 article provides an important clue:

The high incidence of self-mutilation among patients with dissociative disorders in this study, particularly among MPD patients, calls for increased vigilance among clinicians for evidence of dissociation in the patient demonstrating such behaviors. Further, the existence of self-mutilation should alert the clinician to the possibility of an abusive childhood history. Although denial of self-mutilation may signify a factitial disorder, the clinician should also consider the various dissociative disorders and search diligently for evidence of memory loss, which may not be immediately apparent. 1 [ emphasis added ]

Assuming that these recommendations are adopted by a majority of practitioners, there is every reason to believe that the next investigation will succeed in uncovering self-mutilation in well over 50% of MPD patients.

The Discontinuous Nature of Self

Inquire among clinicians who have worked with MPD patients about why they accept the notion of separate personalities within one body, and eventually most will tell you that they were convinced by the evidence. Inevitably, the evidence to which they refer is the behavior of their patients, which differs so dramatically across time that many therapists become convinced that no single, unified individual could possibly display such striking personality transformations. Hence, various sets of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings are identified and conceptualized as separate and relatively independent entities.

Hypnotic Age Regression

The situation is analogous in many ways to that of hypnotic age regression: Whereas MPD seems to involve separate personalities, hypnotic age regression appears to produce a series of functionally distinct ages, each with its own set of behavioral, intellectual, and emotional processes. The affects displayed during age regression can be so intense, and the behaviors so compelling, that it may seem as if earlier developmental periods are actually being reexperienced. Moreover, the descriptions provided during hypnotic age regression are often filled with incredible detail, and it is not unusual for patients to be absolutely certain of the historical accuracy of their reports. In light of this evidence, it is perhaps understandable that many early hypnosis theorists believed that during hypnotic age regression, the individual literally functioned at the suggested age level.

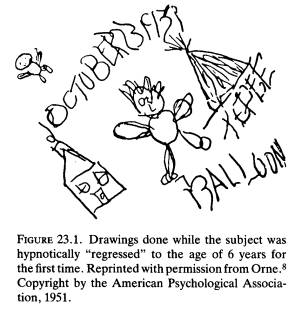

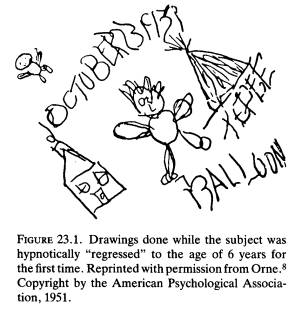

Orne investigated this issue empirically in 1951 with 10 highly hypnotizable Harvard University students.13 In hypnosis, regression to the age of 6 years was suggested, and Rorschach records, as well as drawing samples, were gathered. The identical procedure was then followed with the same 10 students in the waking state. Comparison of the Rorschach records obtained during and after hypnotic age regression revealed many striking differences in language, including the occurrence of numerous childish verbalizations that occurred only during hypnosis. In fact, the behavior and response style of subjects during hypnotic age regression appeared to resemble that of a child 6 years of age; without further study, it would have been easy to conclude that the students were functioning precisely as a 6-year-old would function. However, analysis of the formal characteristics of the Rorschach record --aspects including location, developmental quality, determinants, form quality, and organizational activity --indicated the presence of many features that could not be expected in the record of an actual 6-year-old. Moreover, careful inspection of each "regressed" profile revealed striking inconsistencies: although subjects displayed some characteristics of regression, the specific features exhibited varied across individuals; and each student's profile inevitably contained many qualities far advanced beyond the suggested age.

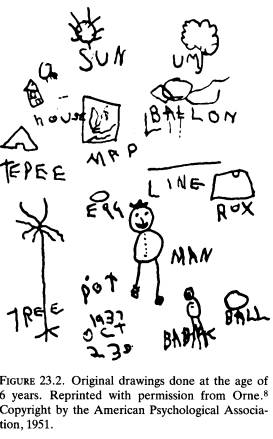

Results for the drawings were even more illuminating because for one of the 10 subjects, it was possible to obtain from the student's father a set of drawings that were made when the student was actually 6 years old, drawings the student had not seen since originally making them. 13 For this individual, drawings made during the study could be compared to those made nearly 15 years earlier, enabling a systematic comparison of the drawings made during

252 Orne and Bates

hypnotic age regression to what was produced by the same individual as a young child. Figure 23.1 shows the drawings of the adult subject made during hypnosis when given the suggestion for age 6. As with the Rorschach records, this drawing looks the part: The lines are drawn rather poorly, the forms show childlike distortion, and so on. However, when Figure 23.1 is contrasted with Figure 23.2, it is clear that the age-regressed drawing bears little resemblance to what was actually generated by the subject at 6 years of age. In fact, the drawings of all hypnotically regressed subjects showed the same characteristic: Although the formal concept was somewhat childlike, the execution of the drawing itself was more like that of an adult. Karen Machover, at the time a leading worker in the field of children's drawings, confirmed this impression (personal correspondence 1949). She noted that the adult drawings intermingled mature and immature features and, in many respects, were more mature than those done outside of hypnosis. She used the term "sophisticated oversimplification" to describe the adult drawings made during hypnotic age regression.

In both Rorschach results and the drawings, then, there is an appearance of regression that, under closer inspection, turns out to be an admixture of regressive-like responses interspersed with a number of more mature responses. 13 The clinical picture is enhanced by several less systematic observations that, nevertheless, provide insight into subjects' internal experiences during hypnotic age regression. For example, when hypnotized and given a suggestion for age 6 years, one subject wrote the following: "I am conducting an experiment which will assess my psychological capacities." Although the handwriting was rather childlike, not a single word was misspelled! A different subject provided another example of what Orne has since termed trance logic. This young man had been in Germany when he was 6 years old and had not yet learned to speak English. During hypnosis, he was given an age-regression suggestion, and told he was at his sixth birthday party. When asked what his mother was saying to him, he replied, in English, "Do you like your

253 Multiple Personality Disorder

present?" The experimenter replied, "Listen carefully, isn't she saying 'Hast du dein Geschenk gern?'," the German equivalent. The subject answered, "Ja." The experimenter then asked him where he was, to which the subject replied, "In Berlin." Next, the experimenter inquired, "Do you speak English?," to which the subject answered, "Nein." "Do you understand English?" "Nein." "Do your parents speak English?" "Ja, damit ich nicht versteh" (So that I shouldn't understand it). "You mean to say you can't understand a word of English?" "Ja." In all, the question was rephrased 10 times, and each time the subject answered, "Nein," he could not understand a word of English -- of course, understanding the question on each occasion!

What can we conclude based on these, as well as more recent, observations?14 First, it is apparent that hypnotic age regression does not result in an individual who functions at the suggested age level, or for whom there is a reinstatement of childhood psychological and physiological faculties. Although the behavior of the "regressed" individual is often compelling, both to patient and to onlooker, systematic inspection of the response pattern reveals striking inconsistencies that leave no doubt as to the incomplete nature of the regressive experience. At the same time, the very existence of these inconsistencies argues against the conclusion that hypnotized subjects are merely role playing the part of a young child. Few individuals would be so naive as to overlook such obvious shortcomings in their performance. Hence, the phenomenon of hypnotic age regression appears to involve a person who has the subjective experience of being younger, but who in fact retains adult modes of cognitive and emotional functioning.

Alter Personalities as Figurative Selves

We believe that the empirical work concerning hypnotic age regression has important implications for understanding MPD. Alter personalities are convincing in the same way as hypnotic age regression. In both instances, the behavior of the individual is striking in its appearance, and an onlooker who has neither the luxury of systematic observation across time, nor access to control subjects, can easily be misled into thinking that the primary personality has given way to an entirely different mode of functioning. Yet, the parallel to hypnosis research is clear. A more careful examination of the performance of alter personalities will reveal the same admixture of functioning that characterizes hypnotic age regression. Child alters, for instance, can be expected to display intellectual and emotional capacities far beyond their stated age, qualifying the behavior as "sophisticated oversimplification." In sum, rather than conceptualize alter personalities as functionally autonomous entities, possessing a full complement of psychological, cognitive, and affective faculties, it is more appropriate to view them as figurative selves, each reflecting some disavowed aspect of the patient's total self. It is precisely because they are symbolic caricatures that they are neither intellectually, emotionally, nor developmentally coherent.

Of course, many MPD theorists will quickly agree that alter personalities are metaphorical creations and that it would be naive to believe that more than one person actually co-exists within the same physical body. Yet, this easy reassurance fails to appreciate the thin line between metaphor and reification and the ease with which this boundary can be inadvertently crossed. This ready assurance also belies the considerable enthusiasm within MPD circles for recent studies that have attempted to document the physiological independence of various alters. In this effort, MPD researchers are traversing the same misguided path traveled some 40 years ago by hypnosis investigators, who, convinced of the literal reality of hypnotic age regression, devoted a tremendous amount of energy to documenting reliable physiological markers of this process. These researchers hoped to demonstrate that hypnotic age regression involved the reinstatement of infant-like EEG activity and childlike reflexes (eg, the Babinski response) and that conditioned responses learned as adults were ablated during regressed states. Although a few preliminary studies were encouraging, this trend quickly reversed once the numerous procedural shortcomings of the early investigations were rec-

254 Orne and Bates

tified. In retrospect, it is painfully clear that we should no more expect for hypnosis to reinstate early childhood modes of functioning than we should anticipate that hypnosis would cause an individual to shrink. Today, a handful of initial reports claiming to have documented the physiological autonomy of alter personalities has generated great excitement within some MPD circles.15,16 Careful study of these preliminary investigations, however, reveals that the methodologies are inadequate. No one familiar with the history of hypnosis should doubt that these preliminary results will go unsubstantiated by future studies that incorporate adequate controls.

The Reconstructive Nature of Memory

Until the last few decades, it was uncommon for patients diagnosed with MPD to report experiencing early childhood trauma. Although these individuals received treatment that was equal in intensity to that provided today -- Miss Beauchamp was seen by Morton Prince3 for over 7 years on a constant, often daily basis -- childhood abuse, sexual or otherwise, was rarely a part of the clinical presentation of MPD. This scenario is in stark contrast to the picture seen today. By 1984, Bliss found that approximately 50% of MPD patients reported experiencing sexual abuse, while just under 40% indicated physical abuse.7 Two years later, a survey of 100 cases of MPD by Putnam and his colleagues found that 97% of the patients reported some form of early traumatic experience, with 83% of the patients indicating childhood sexual abuse, and 75% reporting childhood physical abuse.11 There is now a general consensus within the field of MPD that the condition is the specific result of early childhood trauma.

Multiple Personality Disorder and Childhood Abuse

The evolution of the putative relation between childhood abuse and MPD is reminiscent of the history of the association between MPD and self-mutilation. In both instances, there is a risk that prevailing expectations and beliefs about MPD are shaping the way in which the disorder is manifested. Let us again consider the situation from our patients' point of view. These patients' worlds are confoundingly chaotic; they enter psychotherapy embittered, bewildered, and demoralized, desperate that their condition somehow be understood and treated. Like each of us, they have read about or seen other individuals who described suffering from similar symptoms until previously repressed memories of childhood abuse were recovered. According to these reports, the uncovering of these early traumatic experiences resulted in clinical improvement, sometimes dramatic in nature. Many of these patients have begun to wonder whether in their own past there are episodes of abuse of which they are not yet aware. This suspicion is often shared by their therapists, who from the beginning of treatment, evidence a keen interest in patients' childhood experiences. Specialized techniques such as hypnosis may be used in an effort to facilitate the uncovering process, although it is vital to recognize that false memories can be produced quite apart from the use of hypnotic procedures. As treatment proceeds, and as remote memories continue to be a focus of treatment, therapist and patient achieve an implicit understanding that current symptoms spring from early trauma, that the trauma will eventually be recalled, and that recollection is an essential part of treatment and restoration of health. Of course, such an understanding can also be quite explicit, as illustrated by Bliss:

After the patient is aware of the personalities, I now, early, discuss with her the nature of multiple personalities. I explain that they are a product of self-hypnosis, induced at an early age, without any conscious intent. Experiences occurred that she as a child could not tolerate or manage. However, she is now an adult, strong and capable. If she only will have the courage, these specters can be flushed out, remembered, and defeated. These experiences and feelings must be recalled. 10

Under these circumstances, it would not be surprising for patients to eventually begin to recover "memories" of being abused as children, regardless of whether any abuse actually occurred.

255 Multiple Personality Disorder

In light of the wealth of experimental evidence pointing to the reconstructive nature of memory, there is good reason for us to be very cautious about accepting as historically accurate our patients' recollections about remote events. The fact that various alter personalities will remember the past in diametrically different ways merely underscores the importance of this consideration. Furthermore, although many therapeutic techniques can alter memory -- including free association, dream interpretation, and guided imagery -- the need for discretion is especially acute when hypnosis is introduced, because the problems inherent to memory are exacerbated when individuals attempt to remember in trance. This observation is particularly relevant because hypnosis is considered by some as an essential ingredient in the treatment of MPD, especially when patients are attempting to uncover early life experiences that presumably have been repressed or dissociated from awareness.

The utility of hypnosis in enhancing recall has been one of its most celebrated, as well as controversial, features. The intense emotional reactions of his patients during hypnotic sessions, along with the wealth of detail included in their "recollections," and the often dramatic improvement in their symptoms following the uncovering process, initially convinced Freud that these reminiscences reflected actual autobiographical occurrences. Additional clinical experience, however, soon led him to question the historical accuracy of these hypnotic accounts. Eventually, Freud recognized that, although emotionally valid and of considerable therapeutic usefulness, these events did not necessarily correspond to actual childhood experiences and that they often comprised various amounts of fact, fantasy, and confabulation.

Freud's observations have been confirmed by empirical evidence gathered over the last century regarding hypnosis and memory. Contrary to the clinical impressions of many therapists, no good evidence supports a hypermnesic effect for hypnosis. For instance, in a systematic replication and extension of the widely cited investigation by Reiff and Scheerer,17 O'Connell, Shor, and Orne18 assessed the ability of hypnosis to enhance subjects' recall of remote memories, such as the names of their elementary schools, their teachers, and their fellow classmates. As in the original Reiff and Scheerer study, O'Connell, Shor, and Orne actually reviewed school records for every subject to validate the reports given during and outside of hypnosis. Results made it clear that recall with the aid of hypnosis was no more accurate than that observed in the waking state. The fundamental unreliability of hypnotically aided recall is now one of the better documented findings in the hypnosis literature. 19,20

At the same time, it is important to recognize that individuals are particularly likely to consider their recollections during hypnosis to be historically accurate. Hence, the use of hypnosis in an effort to recover lost memories is likely to result in a person who has a great deal of faith in the accuracy of any "recovered" material. Unfortunately, this unfounded confidence pertains to confabulated as well as correct information. Although the extreme limits of this process are difficult to observe in the context of psychotherapy, because as clinicians we are more interested in the meaning of the abreacted material than in challenging its veridicality,21 it becomes all too apparent in forensic settings. As a result of their undue faith in hypnotically elicited memories, these witnesses tend to be extremely confident of their testimony. Furthermore, their faith can be virtually unshakable, rendering them effectively immune to attempts at cross-examination. Now, in numerous cases, a witness was initially uncertain about the events in question, but subsequent to hypnosis became convinced and in turn provided persuasive testimony that led to the indictment and conviction of an individual.22

False Memories and Clinical Improvement

Although most practitioners have employed hypnosis in an effort to recover memories of remote experiences, Janet occasionally used trance to purposefully replace traumatic recollections with less disturbing ones.23 His case of Marie is illustrative of this technique. This young woman suffered numerous hysterical symptoms, among them a blindness in one eye which had begun at age 5 years when she was

256 Orne and Bates

forced to sleep with a child who had impetigo covering the left side of her face. Marie developed impetigo also, and once cured of it, displayed a blindness in her left eye that persisted. During hypnotic age regression, Janet suggested that Marie was again 5 years old and was sleeping with the same child. However, Janet strategically reconstructed the memory of this experience by suggesting that the child's skin was clear and smooth, free of disfigurations. As a result of this intervention, Marie's hysterical blindness was cured! Janet's treatment dramatically underscores the notion that treatment success does not depend on veridical memories being uncovered and worked through. The view that effective interpretations must be historically accurate appears to be a mistaken one. Just as importantly, Janet's work cautions us against inferring the authenticity of remote memories solely on the basis of clinical improvement. The fact that our patients' symptoms may diminish following the apparent recovery of traumatic memories does not mean that the memories are of genuine autobiographical experiences.

The implications of this work for MPD should be evident. It is a mistake to accept, without independent corroboration, the historical accuracy of patients' verbal reports concerning their childhood experiences. On its own, the fundamental unreliability of remote recall argues strongly against such a practice, especially when used in an attempt to advance the scientific basis of psychology and psychiatry. The problem is compounded by the fact that most of these "recollections" occur in the context of psychotherapy, frequently during hypnosis. Given our current knowledge, official pronouncements concerning the etiology of MPD are both premature and unwarranted.

Implications for the Treatment of Multiple Personality Disorder

What inferences can be drawn from these observations regarding the treatment of MPD? Certainly, one implication concerns the powerful influence that we as therapists can have on the presentation and course of the condition. Much of the symptomatology seen in MPD may result from the mutually shared expectations of therapist and patient. As clinicians, we must therefore be extremely careful that, in our effort to treat a patient, we do not inadvertently exacerbate the symptoms. As long as MPD is considered primarily a problem of multiple selves, a fundamental component of treatment will continue to be the identification and elaboration of alter personalities, and this very process carries a substantial risk that these metaphorical entities will gradually assume a life of their own.

From the initial diagnostic sessions, during which inquiries are made concerning the possible existence of alternate selves; to the hypnotic explorations for these selves; to the naming and interviewing of each separate self; to the almost inevitable colluding with certain selves by agreeing to keep secrets from others; to the eventual struggle over reaching consensus among the various selves to enable unification -- every step of treatment has the potential to reify what is only a metaphor. The same is true of many specialized techniques currently used to treat MPD, including "alter substitution" and "reconfiguration" interventions in which the therapist bargains with various alters in an effort to pass control from one "personality" to another.24 It becomes difficult to imagine a patient undergoing this form of treatment without eventually believing in the literal reality of some, if not all, "personalities."

Multiple Personality Disorder Conceptualized as a Memory-Based Disorder of Self

An alternative approach to the treatment of MPD recognizes that without a proclivity toward forgetting, the condition would not exist as a unique diagnostic category. It is their extreme dependence on dissociation that distinguishes MPD patients from those diagnosed as borderline, schizophrenic, and bipolar. Thus, MPD can be considered as a disorder of self, deriving primarily from a problem of memory. Viewed in this light, it becomes clear that one major goal of psychotherapy is to consolidate

257 Multiple Personality Disorder

the self by helping the patient learn to remember events that are more easily forgotten.

During psychotherapy, the patient with an extreme tendency to dissociate often finds it impossible to recall events that were discussed in previous sessions. Such a severe memory problem can lead to an impasse in therapy: Even though the patient may be expressing and working with intense feelings, the therapeutic process somehow fails to move forward in the larger sense. To deal with this very serious problem, it may be necessary to intervene directly by providing the patient with tools that can be used to prompt memories of earlier sessions. One procedure that the senior author has used on occasion is to audiotape therapy sessions, with the patient's consent, of course. The patient is then asked to return to the therapist's office before the next session to listen to the tapes. If necessary, the patient can listen to crucial sessions more than once, and some patients may find it necessary to take notes. The goal is to help the patient become aware of the differences between what is remembered of each therapy hour and what actually occurred during the session. This approach also places responsibility with the patient for remembering the important events that occur during treatment.

This tedious approach demands a great deal from the patient, but the advantages can be considerable. Now, often for the very first time, the patient becomes able to trace the origins of feelings and achieves an understanding of previously mysterious motivations and desires. As the dissociative fog slowly recedes, thoughts and emotions that once seemed islands in a sea of uncertainty are able to be recognized as connected parts of a coherent inner world. As this process continues, the patient becomes increasingly more able to participate as an equal partner in the therapeutic alliance.

Instilling Responsibility for Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors

Over time, the sense of self can develop to the extent that the patient can begin to attend to her own behavior as well as to that of others. As the patient gradually relies less on dissociation and repression, therapy will necessarily focus on the discordant thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are experienced as unacceptable. During this process, if a therapist elects to describe a patient's experiences in terms of "parts of the self," it is essential that the "parts" in question are understood to be various emotions and actions, and not autonomous personalities.25

The rationale for working with feelings rather than alters, disavowed actions rather than sovereign selves, is in contrast to an approach that treats each personality as an independent entity, with its own complement of psychological, emotional, and physiological functions. From both a conceptual and therapeutic standpoint, the reification of alters is entirely unnecessary. The problem becomes particularly serious from the perspective of treatment because one of the fundamental goals of any type of psychotherapy must be to encourage patients to become aware of their feelings and accept responsibility for their actions. This process is not advanced when individuals stop believing that "The devil made me do it," only to learn that "My alter made me do it." By attributing disavowed parts of the self to autonomous "personalities," the current approach toward treatment merely postpones to the future the now even more formidable task of helping patients integrate their discordant thoughts and feelings. Worse still, some patients may find solace in the knowledge that they are not liable for the irresponsible, sometimes violent, conduct of their other "selves," perhaps increasing the probability that such behavior will occur. Having once experienced the comfort of a life without accountability, these individuals may be particularly prone to relapse when future stressors are encountered.

Managing the Problem of Imperfect Memory

Finally, it is an error to accept as historically accurate our patients' recollections of remote events. This observation has definite implications both for research and treatment. With regard to the former, investigations concerning the etiology of MPD simply cannot rely on patients' self-reports of their childhood experiences. These reports are inherently unreliable,

258 Orne and Bates

given the reconstructive nature of memory and the limitations of remote recall. For this reason, studies that depend on patients' recollections to ascertain the origins of MPD do not advance the field. In fact, because patients' reminiscences reflect the expectations and beliefs they come to share with their therapists, it is almost inevitable that such investigations will produce results that confirm views popular at the time. Unfortunately the field is now worse off than it was before, because hypotheses previously considered speculative now appear to have received empirical confirmation.

With regard to treatment, the unreliability of remote recall should caution us against conducting therapy with the assumption that our patients' memories are accurate autobiographical accounts. Certainly, there can be no doubt that some patients do endure serious and very damaging abuse, and that within the supportive context of psychotherapy previously repressed memories of these events may become conscious. Given the reconstructive nature of memory, however, it is inevitable that remote memories will interweave fact and fantasy, even when the recollections are based on traumatic events that did occur. As a consequence, there are extremely few instances in which it is possible for either patient or therapist to know with confidence what actually happened in the patient's distant past.

For this reason, if patients are considering legal recourse for an alleged abuse, we as therapists must remain clear that our primary responsibility is to facilitate their psychological and emotional growth. As with any major life decision, this choice may be discussed in therapy but ultimately must be made by the patient. It is not appropriate for therapists to place themselves in the position of counseling patients to sue their parents for presumed childhood abuse, and those who do so should take careful stock of their own countertransference feelings. Patients who desire to confront alleged perpetrators may begin by understanding their own feelings of victimization and anger; those who remain adamant in facing their alleged abusers should generally be encouraged to do so within the context of therapy, an environment more likely to promote healthy resolution than the courtroom. Throughout, therapists' attitudes should implicitly convey the message that memory is reconstructive and that our recollections of remote events are invariably an admixture of fact and fantasy. The issue is not determining whether our patients' memories can be believed, but rather, discerning the meanings and feelings accompanying the memories so that patients can make sense of their experiences and find a way to move ahead with their lives.

Risks and Benefits of the Therapeutic Process

It is also vital to understand that the therapeutic process of "uncovering" remote events is anything but the risk-free venture that some practitioners consider it to be. Just as Janet's work23 demonstrates that distant memories can be altered in a positive way to help patients, it is likewise the case that remote memories can be reconstructed in a negative manner and can have a very destructive influence on patients' lives and on the lives of those who care for them. False "recollections" of childhood abuse can cause patients to become even more confused, disorganized, depressed, and self-destructive. As a result of these "memories," patients' feelings of victimization and helplessness may be heightened, their perception of personal responsibility reduced, and their sense of social isolation intensified. If matters are allowed to get even further out of hand, entire families can be literally destroyed. Hence, there is reason to be concerned about treatment regimens that rely on "recreating" a traumatic past for each patient, vivifying negative "memories" without recognizing their dubious authenticity or potentially deleterious effects.

In the end, a traditional approach toward psychotherapy, in which the meaning of patients' recollections is our primary concern, continues to be an appropriate form of intervention. Although it is easy to become captivated by the intricate and dramatic descriptions provided by MPD patients concerning their early childhood, we must guard against relying on this process as an end unto itself. The task of therapy is to assist individuals in living more

259 Multiple Personality Disorder

healthy lives now and in the future. In this regard, psychotherapy with MPD patients would cease to be an esoteric enterprise in which separate and uncooperative alters must be cajoled into fusing; instead, therapy would proceed as it does with any patient, along the traditional lines of gently enabling patients to understand and take responsibility for their own wishes, desires, hopes, fears, and behaviors.

Summary

Multiple personality disorder, once a rare condition, has become a rather common diagnosis today. It appears that there has been a fundamental change in the essential nature of the disorder, so that what was a relatively benign condition has transformed into one of the more grim mental illnesses of our time. Like MPD, hypnosis has also undergone periods of metamorphosis over time. In fact, close study of the history of hypnosis provides an illuminating perspective from which to view the present issues facing those interested in MPD. Workers in both fields have had to wrestle with similar problems, including the ephemeral nature of dissociative conditions, the discontinuous nature of self, and the reconstructive nature of memory.

The manner in which these problems are addressed has profound implications for the psychotherapy of dissociative disorders. As with hypnosis, the way in which MPD is manifested is influenced greatly by prevailing cultural attitudes and expectations. It is possible that the dangerous symptomatology currently associated with the disorder, as well as the condition's unfavorable prognosis, is shaped by the convictions of those who treat it. Similarly, therapists must exercise extreme caution lest they unwittingly convey to patients the mistaken idea that they indeed host independent selves. Although both hypnotic age regression and MPD are characterized by behavior that appears to reflect the existence of functionally distinct entities, each process is more appropriately conceptualized as involving aspects of a single self. Finally, the reconstructive nature of remote recall renders it particularly vulnerable to alteration. Apparent memories of childhood experiences inevitably interweave truth and fiction, and their veridicality should not be assumed without independent verification.

We advocate a treatment approach that considers MPD to be a disorder of self deriving from a problem of memory. This conceptualization contrasts with other models that understand MPD as primarily a problem of multiple selves. Whereas the latter approach focuses on the identification and elaboration of alter personalities, the former treats the patient as a single self, while at the same time helping the individual learn to remember and accept discordant thoughts and feelings. Rather than accept remote memories as historically accurate, we suggest that they be viewed as an admixture of fact and fantasy and that therapy focus on their meaning rather than their accuracy. We believe that this alternative treatment approach is more likely to promote meaningful progress in psychotherapy and to encourage patients to accept responsibility for their own behavior.

Acknowledgments. The conceptual evaluation on which this manuscript is based was supported in part by grant MH44193 from the National Institute of Mental Health, US Public Health Service, and in part by a grant from the Institute for Experimental Psychiatry Research Foundation. We are grateful to Emily Carota Orne and David F Dinges for their comments and suggestions for improving this paper.

References

1. Coons PM, Milstein V. Self-mutilation associated with dissociative disorders. Dissociation. 1990; 3: 81-87.

2. Loewenstein RJ, Putnam FW. The clinical phenomenology of males with MPD: a report of 21 cases. Dissociation. 1990; 3: 135-143.

3. Prince M. The Dissociation of a Personality. 1908. New York: Meridian Books; 1957.

4. Kluft RP. Treatment of multiple personality disorder: a study of 33 cases. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1984; 7: 9-29.

5. Putnam FW. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multi-

260 Orne and Bates

ple Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1989.

6. Wilbur CB, Kluft RB. Multiple personality disorder. In: Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1989: 2197-2216.

7. Bliss EL. A symptom profile of patients with multiple personalities -- with MMPI results. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1984; 172: 197-202.

8. Orne MT. The nature of hypnosis: artifact and essence. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1959; 58: 277-299.

9. Szasz TS. The Myth of Mental Illness. New York: Harper & Row; 1974.

10. Bliss EL. Multiple personalities: a report of 14 cases with implications for schizophrenia and hysteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980; 37: 1388-1397.

11. Putnam FW, Guroff JJ, Silberman EK, Barban L, Post RM. The clinical phenomenology of multiple personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1986; 47: 285-293.

12. Coons PM, Bowman ES, Milstein V. Multiple personality disorder: a clinical investigation of 50 cases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988; 176: 519-527.

13. Orne MT. The mechanisms of hypnotic age regression: an experimental study. J Abnorm Soc Psychol.1951; 46: 213-225.

14. Nash M. What, if anything, is regressed about hypnotic age regression? A review of the empirical literature. Psychol Bull. 1987; 102: 42-52.

15. Coons PM, Milstein V, Marley C. EEG studies of two multiple personalities and a control. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982; 39: 823- 825

16. Putnam FW. The psychophysiologic investigation of Multiple Personality Disorder: a review. Psychiat Clin North Am. 1984; 7: 31-39.

17. Reiff R, Scheerer M. Memory and Hypnotic Age Regression. Developmental Aspects of Cognitive Function Explored Through Hypnosis. New York: International Universities Press; 1959.

18. O'Connell DN, Shor RE, Orne MT. Hypnotic age regression: an empirical and methodological analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1970; 76(monogr suppl 3): 1-32.

19. Orne MT, Soskis DA, Dinges DF, Orne EC. Hypnotically induced testimony. In: Wells GL Loftus EF, eds. Eyewitness Testimony: Psychological Perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1984: 171-213.

20. Orne MT, Whitehouse WG, Dinges DF, Orne EC. Reconstructing memory through hypnosis: forensic and clinical implications. In: Pettinati HM, ed. Hypnosis and Memory. New York: Guilford Press; 1988: 21-63.

21. Spence, DP. Narrative Truth and Historical Truth: Meaning and Interpretation in Psychoanalysis. New York: WW Norton; 1982.

22. State v Mack, Minn 292 NW2d 764 (1980).

23. Janet P; Paul E, Paul C, trans. Psychological Healing: A Historical and Clinical Study. New York: Macmillan; 1925.

24. Kluft RP. Playing for time: temporizing techniques in the treatment of multiple personality disorder. Am J Clin Hypn. 1989; 32: 90-98.

25. Orne MT, Bauer-Manley, NK Disorders of self: myths, metaphors, and the demand characteristics of treatment. In: Goethals RD, Kavanaugh RD, Strauss J, eds. The Self: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Springer-Verlag. 1991: 93-106.

Figs. 23.1 and 23.2 (p. 252) (from Orne, M.T. The nature

of hypnosis: Artifact and essence. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,

1951, 58, 277-299.) are reproduced here with the kind permission of the American

Psychological Association © 1951. No further reproduction or distribution

of these figures is permitted without written permission of the publisher.