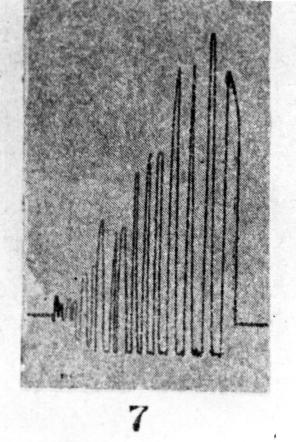

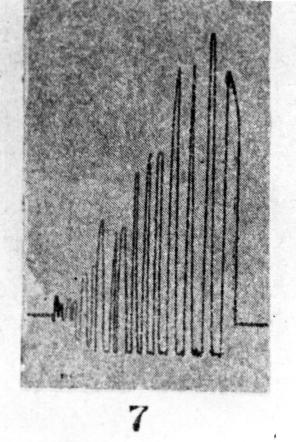

Tracing of a knee-jerk reflex

Twitmyer received his bachelor's degree from Lafayette College in 1896. In the Following year he became instructor in psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, and the rest or his career was spent at that University. There he received his doctoral degree in 1902, and there also he was appointed professor in 1914 and director of the Psychological Laboratory and Clinic in 1937. At the time of his death he was nearing the end or his 46th year or service at the University.

When Twitmyer came to Pennsylvania, the Psychological Clinic was in its early infancy, having been established by Lightner Witmer during the previous year (1896). His own interests were soon drawn into this direction, and he was active in the efforts which were successfully made to interest the public, and particularly teachers in the public schools, in the use of the clinic's facilities. His first wife, Mary Marvin Twitmyer, was a teacher or the deaf, to whom Witmer during the clinic's first year had turned for assistance in the treatment of a case of defective speech. From her Twitmyer derived an interest in this field; and in 1914 the special clinic for the treatment of speech defects was established with him as its head. To this work, thereafter, he devoted a large share or his energies. In Correction of Defective Speech (1932), written in collaboration with Y. S. Nathanson, he expressed the point of view to which he consistently adhered, that in spite or the great variety of organic and psychological correlates of disorders or speech, disturbances of the normal rhythm of breathing constituted the closest approach to a common etiological factor, that these disturbances were, in part, of an habitual nature, and that they could frequently be treated by methods designed to break bad habits and establish good ones.

The story of Twitmyer's doctoral dissertation is not without interest for the history of psychology. He began with the intention or studying the variability of the patellar tendon reflex under both 'normal' and facilitating conditions. During the course or the experiment, however, he observed by accident a more interesting phenomenon. He himself has described it in the published dissertation:

"During the adjustment of the apparatus for an earlier group of experiments with one subject (Subject A) a decided kick of both legs was observed to follow a tap of the signal bell occurring without the usual blow of the hammers on the tendons. ... Two alternatives presented themselves. Either (1) the subject was in error in his introspective observation and had voluntarily moved his legs, or (2) the true knee jerk (or a movement resembling it in appearance) had been produced by a stimulus other than the usual one.''

Further experiments convinced him that the phenomenon was not an artifact. It appeared in the case of each of the six Ss upon whom the experiment was attempted, although from 150 to 238 preceding trials with combined stimulation by bell and hammers were necessary. The stability of the response to the bell alone was round to be a function of the number of combined stimulations. No difference in the form of the graphic records of the new response and those of the normal knee jerk was observed, but he pointed out that such differences might require a faster-running kymograph to be made visible. Finally, not only did the Ss insist that the responses were not voluntary, but in some cases they found themselves unable to inhibit the response even though they made a great effort to do so. The report concluded with a statement of the intention to carry out further investigations of the new phenomenon.

To account completely for the fact that these investigations never materialized would require knowledge of matters not accessible to the historian. But more than this needs to be explained. As every psychologist knows, it was at this same time that very active and purposeful research was going forward in the laboratories of Pavlov and Bekhterev; and it is clear that in Pavlov's case, as in Twitmyer's, conditioning was first observed as an unexpected outcome of experiments which were directed toward a different end. Why should the history of conditioning have had its effective beginnings in the work of the Russians rather than among the psychologists of this country?

It is probably not sufficient to point to the obscurity of Twitmyer's work which resulted from his dissertation having been privately published. The findings of his experiment were reported before the American Psychological Association at its Christmas meetings in Philadelphia in 1904, with William James presiding. Twitmyer's own recollections of this occasion were always mingled with feelings of disappointment at the failure or his auditors to express interest in his results, of which he recalled no discussion whatever. In addition, psychologists in this country had abundant opportunity to read the abstract of this paper, published in the proceedings of the meetings [Knee jerks without simulation of the patellar tendon, Psychological Bulletin, 2, 1905, 43 f.]. Brief as it is, this abstract presents perfectly clearly the essentials of the discovery, a spark surely sufficient to fire the imagination of anyone who was adequately prepared for it.

In this last suggestion, probably, the historical moral is to be found. The intellectual climate in which lived the American psychologist of the first years of this century was such that Twitmyer's first thought, when his Subject A produced a leg-kick to stimulation by bell alone, was apparently the question whether the S's introspection was in error. Pavlov, on the other hand, was first or all a physiologist, not directly concerned with his Ss' mental processes; and, in any case, he was dealing with animal Ss whose introspections could not be asked for. His results, therefore, easily presented themselves to him as affording an objective means or studying the activity of the central nervous system. Twitmyer's results, however, fell naturally into the context into which he himself placed them: that is, as an interesting extension of the law of contiguity. It must be recalled that even in 1914, and while formulating the behavioristic program, Watson rather deprecated the use of Pavlov's methods for psychological investigations. Thus, we may see in this whole episode the manner in which scientific progress is affected by the investigator's point of view.

Although he was first and foremost a clinician, Twitmyer always retained his interest in experimental psychology. His conviction that laboratory experience was as necessary for the training of the clinical psychologist as that of the experimentalist was expressed in the emphasis which he placed upon the laboratory as a major part of the course-work even in the undergraduate's first introduction to psychology. For this his students have owed him gratitude. His personal qualities, also, were such as to make him to an unusual degree a focus of the affection and loyalty of his students, colleagues, and friends.

The University of Pennsylvania

Francis W. Irwin

From The American Journal of Psychology, 56, 451-453, 1943.

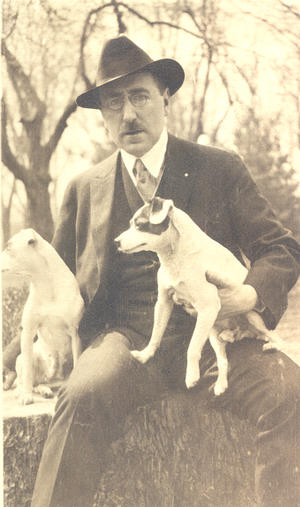

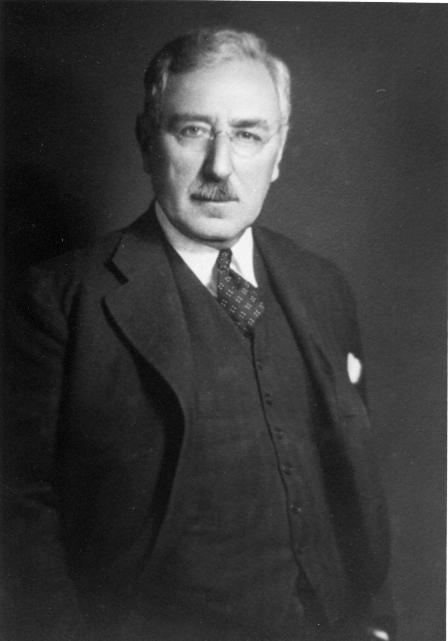

A more mature picture of Prof. Twitmyer

A more mature picture of Prof. Twitmyer