Arctic Zirkle

Champion Musher Answers the Call of the

Wild

One of the things Aliy Zirkle, C'92, loves best about riding on the runners

of her dog sled is listening to the great, snow-muffled silence that rules

the Far North. When she came to Alaska almost a decade ago to monitor

the wolf population for the Department of Fish and Game, she lived about

35 miles above the Artic Circle in the village of Bettles (1990 population

36). Villagers advised her to buy a snowmobile. The raucous machine screeched

and smoked across the trackless snowfields of the Brooks Range, where

she explored ice-crusted forests and rivers, rugged mountain faces and

glacier-carved valleys, and a vast coastal plain that stretched to the

horizon and sometimes flowed black with tides of migrating caribou. "Come

spring," she recalls, " my back hurt, and I had a constant ringing

in my ears."

To preserve her auditory health as well as her intimacy with the kingdom of cold and silence, she acquired some trapline dogs—dogs that pull the sleds of trappers—some pups, a few dogs rescued from a flooded river, and "rejects" that included a favorite named Skunk. With these quiet-running power sources tethered to a gangline at the front of a sled, she could hear the owls hoot and the wolves howl.

"I love it because it's quiet," she says. "When you first hook up the dogs, they're excited to go, and they're talkin' to you and yellin', 'Hook me up first! Hook me up first!' But once you're on the sled and you take off, there's complete silence. You hear little pitter-patters of their feet across the snow, and once in a while you hear little pants."

Talk to the Animals

It's not only dogs that speak to Zirkle. She hears the strange voices

of many nonhuman things. She loves nothing more than to pack up provisions

and camping gear aboard her sled, whistle up the dog team, and disappear

into the bush for weeks at a time.

Sitting

alone within the little circle of light her campfire casts, she has often

watched the northern lights flare, shimmer, and fade across the star-glazed

night. The aurora borealis, she understands, is "really" just

radiation emitted when particles riding on the solar wind are captured

by Earth's magnetic field and conducted through the atmosphere. But when

the curtain of ghostly light unfurls, draping the night in hues of yellow,

green, red, and purple that meekly tint the tips of trees, the science

fails to inform her experience. It's the difference between knowing the

chemical formula that describes an apple's molecular structure and taking

a bite of the apple.

Sitting

alone within the little circle of light her campfire casts, she has often

watched the northern lights flare, shimmer, and fade across the star-glazed

night. The aurora borealis, she understands, is "really" just

radiation emitted when particles riding on the solar wind are captured

by Earth's magnetic field and conducted through the atmosphere. But when

the curtain of ghostly light unfurls, draping the night in hues of yellow,

green, red, and purple that meekly tint the tips of trees, the science

fails to inform her experience. It's the difference between knowing the

chemical formula that describes an apple's molecular structure and taking

a bite of the apple.

"There's no guessin' where it's goin' across the sky or when it's gonna go away," she ruminates. "It dances around, and it talks to you. I'm not really sure it's anything I can understand—I don't really know if it's my language."

Zirkle took off the spring semester of sophomore year to answer a magazine ad inviting her to "go to Alaska and find your dreams." She worked on a bird survey near King Salmon, a fishing village. "I lived on the Alaskan peninsula in between these active volcanoes that had snow-covered peaks all year long. There were brown bears everywhere and caribou. It was like a picture postcard—but it was real. It took a little bit of convincing to get me back to Philly."

She

returned to Penn, but almost immediately after graduation, departed for

the Alaskan interior. "The land just overcame me," she says.

"Since then, really, there has been a calling for me to come here."

Today her home is in Two Rivers (pop. 450), just north of Fairbanks, where

she breeds and trains sled dogs at a kennel (pop. 50) called Skunk's Place.

She

returned to Penn, but almost immediately after graduation, departed for

the Alaskan interior. "The land just overcame me," she says.

"Since then, really, there has been a calling for me to come here."

Today her home is in Two Rivers (pop. 450), just north of Fairbanks, where

she breeds and trains sled dogs at a kennel (pop. 50) called Skunk's Place.

Two Rivers

Not exactly a town, Two Rivers is more a random collection of cabins on

dirt-road spurs off Steese Highway, one of the few paved thoroughfares

in that part of the state. The nearest cabin to Zirkle's is about a half

mile, as the crow flies. It belongs to two brothers, who spend a good

part of the year working traplines. They buzz Zirkle's house whenever

they fly in from the bush to let her know they're home.

The business district consists of a heavy-equipment rental spot, a laundromat, and Tacks' General Store, which sells hardware and fuel but also has a post office and a café that serves breakfast, sandwiches, and homemade pies. "Whenever you stop by," notes Zirkle, "you always haveta' talk dogs."

That's because Two Rivers is by most accounts the dog mushing capital of the world. The woods are woven with dog sled trails. Many of the world's most competitive mushers have kennels and train there, and most residents keep at least a recreational team. "There are more sled dogs out here than horses, cats, people, snow machines, and trucks combined," she contends. "When you drive down the road and pull off at your neighbor's house, it's most likely that you'll see 12, 14, 16 eyes lookin' atcha."

Zirkle designed and built the three-story, cedar-sided structure she lives in—luxurious compared to the one-room cabin she used to inhabit. The woodstove in her old place couldn't keep the plumbing from freezing in January, but she could store frozen salmon for the dogs in its bathtub. "[My new home] has a little balcony that looks off the top story," she says, "right over the dog yard. You can slide open the door off the bedroom and talk to the dogs in the morning."

She

learned construction skills after grasping the fact that real money in

Alaska is in blue-collar work. So she signed on with teams of workers

who built mostly low-income HUD homes out in the bush during the summer

months. In winter, she worked with her dogs and trained for long distance

mushing—primarily in preparation for the Yukon Quest and now the

Iditarod. She no longer does construction work, or waitressing and bartending,

or any of the other odd jobs that used to support her main interest. "I

would say that basically the dogs are my job now."

She

learned construction skills after grasping the fact that real money in

Alaska is in blue-collar work. So she signed on with teams of workers

who built mostly low-income HUD homes out in the bush during the summer

months. In winter, she worked with her dogs and trained for long distance

mushing—primarily in preparation for the Yukon Quest and now the

Iditarod. She no longer does construction work, or waitressing and bartending,

or any of the other odd jobs that used to support her main interest. "I

would say that basically the dogs are my job now."

Her first dogs came from villages of mostly indigenous peoples just south of Bettles, an area of Alaska that old-time breeders say is the bloodline source for the best sled dogs. Skunk's Place is just beginning to see the fourth generation of offspring from a lineage that combines good-natured, hard-working trapline dogs and tough, leggy sprint dogs. She refers to them fondly as "the fellas" and practices a kennel philosophy that blends rigorous training with large doses of play. "I run dogs because I enjoy it and they enjoy it," she stresses. "I do push them to their limits, but I push myself just as hard."

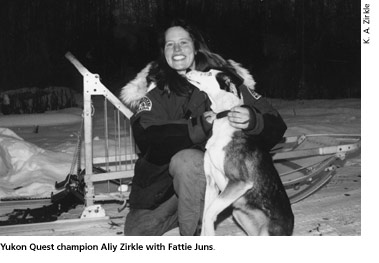

Journalist John Balzar wrote an account of the 1998 Yukon Quest International Sled Dog Race in his book Yukon Alone. It was Zirkle's first attempt at the epic race across 1,023 miles of often harsh wilderness between Whitehorse, in Canada's Yukon Territory, and Fairbanks. She came in seventeenth in her rookie run, fourth the following year, and in 2000 she became the first woman and youngest competitor to win the Quest.

Balzar describes her as "a broad-shouldered beauty with a dazzling smile. Also tough as flint." She is almost six feet tall with blue eyes and long blond hair. "I don't know if there is anything as right-on-the-nose for what I'm doing as my degree in the biological basis of behavior," she points out, although she also admits that throwing the hammer for women's track may have been right on the mark too.

Last Great Race

The Iditarod, which winds through a thousand-plus miles of wilderness

trail from Anchorage to Nome, is the other long distance dog sled race.

Because it garners more media attention and big-money sponsors, it is

better known than the Quest. "There's only one Indianapolis 500,"

Zirkle quips, "and that's the Iditarod." She ran the Iditarod,

which fashions itself "the last great race on earth," for the

first time last year and is registered for the 2002 running in March.

The Yukon Quest, touted as "the toughest sled dog race in the world," takes place in the heart of winter, when most of the Alaskan day is night (17.5 hours of darkness), and follows a more northern route along the old trails of the Klondike gold rush. Temperatures routinely drop to 40 degrees below zero with wind chills that can plunge to minus 80, a cold so fierce and unforgiving that simple mistakes can quickly snowball into disaster and death. There is no provision for calling off a Quest due to severe weather. Mushers have been known to claw their way up mountain slopes on all fours in the teeth of gale-force winds and whiteout blizzards, trusting the dogs to keep them from the edge of a precipice.

The

Quest allows fewer dogs per team than the Iditarod, and there are fewer

checkpoints, with as much as 200 miles of frozen wilderness between some

stopovers. "Basically," Zirkle explains, "the whole idea

is that you're on your own—you and your dogs."

The

Quest allows fewer dogs per team than the Iditarod, and there are fewer

checkpoints, with as much as 200 miles of frozen wilderness between some

stopovers. "Basically," Zirkle explains, "the whole idea

is that you're on your own—you and your dogs."

Both races are endurance contests, demanding good strategy, strict discipline, and barrels of luck. Despite the Quest's superlative, toughest, Zirkle is unwilling to concede that one race is harder than the other. "Every year is different for every racer," she offers.

Participating mushers wear miner's lights on their heads and pack sleds with everything needed to be self-sufficient in the wilderness: ax, arctic sleeping bag, extra gloves and parkas, food, booties and ointments for dogs, an alcohol stove with a large pot, and other survival gear. Designated resupply points along the route keep provisions the mushers have shipped before the race. There is also a crew of veterinarians to monitor the dogs, but no people doctors. Jerry Louden, Zirkle's former kennel partner, gashed his arm during the 1998 Quest and was on his own to find someone to stitch up the wound.

The conventional wisdom in long distance mushing holds that an equal amount of time (five to ten hours) on the trail and an equal amount of rest will take you a thousand miles safely. Each musher develops a strategy of rest and running that works best for their team. The most successful competitors stick to it and don't get caught up in how other mushers are racing. "A lot of people screw up by going too fast at the beginning," says Zirkle. "They burn themselves out and their dogs out. If you're not on your game plan, you usually fall apart by the end."

Like medical care, rest is more for the dogs than the mushers. A typical "rest" stop entails unpacking the sled and lighting the burner to melt snow and boil frozen dog food. As the meal cooks, each dog must be examined for injuries and their feet are massaged with ointment—that's 56 feet for a full team. While attending to them, Zirkle likes to coo encouragement to the sensitive dogs and use her roughhouse voice with the "burley boys." When the dogs are eating, the musher examines and repairs the lines, harnesses, and sled. There's time for a bite to eat and maybe an hour nap before repacking the sled and putting on the 56 booties the team wears to protect its paws.

"You do the same thing over and over for about 10 days," says Zirkle. "You have to go fast; you have to take care of your dogs; you have to take care of yourself." The latter seems the most problematic when mushers start to suffer the effects of sleep deprivation around the fourth day. "Towards about day eight," Zirkle remarks, "you've plateaued. It's almost like you're in a little bubble, but you're not hallucinating anymore." In one race, a musher checked into a warm hotel just 50 miles from the finish line. He had to be kicked awake by another racer, who found him sleeping in a snow bank. "There is a possibility of loss of life," she says, "but riding my bike down Market Street always felt the same way."

Just as important as staying with the game plan is knowing how to cope when luck turns bad—as it almost always does. Some mushers have been attacked by moose; others have fallen through the ice. In her first Quest, Zirkle continued racing despite suffering for several days from a high fever and flu. After winning the 2000 Quest, she was thought by many Iditarod watchers to be the one to beat. Not long after starting down the trail for the 2001 Iditarod, her team was struck down by a respiratory virus, and she had to drop five dogs. The rules don't allow replacements. Ordinarily, mushers find themselves racing at some point in arctic storms, but in last year's Iditarod, Zirkle had to mush through 50 miles of mud during unusually warm weather. "The whole trick to doing well has to do with keeping yourself centered [while enduring] sleep deprivation and cold weather—basically keeping your mind on your goal, which is pretty complicated when you have so many things usually going wrong."

Just Want to Go

In her conversation, Zirkle often talks about "the dog world,"

but she doesn't always use the expression in the same way. Sometimes she

means the world of mushers and breeders who know each other and share

a body of expertise. In that world, she has become a celebrity. At other

times, she uses the expression to mean the world of canine consciousness:

how a puppy grows into a leader who's revered by the team or how a sled

dog pulls for the sheer joy of pulling. She knows this world from the

inside too, not because she fulfilled the psychology requirement for a

degree in the biological basis of behavior, but because she lives so intimately

with her dogs, tending to and playing with them, leading them in the bush

during long, long hours of training and racing, breathing in the rank

breath of dog as she talks to them—or listens.

"You're

goin' down the trail and you turn your light out and it's dark,"

she muses, "and you have stars—really bright ones—and you

can see the outlines of [the dogs'] heads and the breath coming from their

mouths and a little aura coming from each of them. You feel like you're

floating.…It's like you're dancing with them." It's a passion,

she says, that she hasn't quite figured out yet, like a scientific theory

that still needs a few equations worked out to make sense. "It's

just you and your team, and that's all it is." Just pulling. Just

joy. Just listening to the lyrics of silence and dancing with the dogs

among stars that seem so near.

"You're

goin' down the trail and you turn your light out and it's dark,"

she muses, "and you have stars—really bright ones—and you

can see the outlines of [the dogs'] heads and the breath coming from their

mouths and a little aura coming from each of them. You feel like you're

floating.…It's like you're dancing with them." It's a passion,

she says, that she hasn't quite figured out yet, like a scientific theory

that still needs a few equations worked out to make sense. "It's

just you and your team, and that's all it is." Just pulling. Just

joy. Just listening to the lyrics of silence and dancing with the dogs

among stars that seem so near.

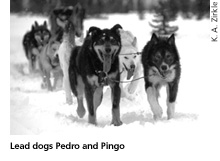

Zirkle held Pedro, the lead dog who brought the team across the finish line to win the 2000 Quest, when he was a pup. Now she's fondling and watching the newest litter of white puppies in the dog yard—how they interact, who's the first to jump out of the doghouse. She can tell pretty early which ones will grow into lead dogs. "They have a certain drive about them," she says. "They don't care who's in front of them; they just want to go."

She has her eye on Frita, a small, intense, and athletic female who's just a year old. Yearlings don't usually make good lead dogs; they prefer to play with the dogs behind them—"because it's fun," Zirkle smiles. But she decided to try Frita at the front of the team, despite her immaturity. "She just had that look about her: She wanted to go—more than anything." Zirkle expects the canine prodigy to become one of the more talented leaders to come out of Skunk's Place.

Only two women have won the Iditarod, and only three men have won both the last great race and the world's toughest. Since winning the Quest, Zirkle has been hearing another voice, but this one speaks a language she can understand. It tells her to forget about who's in front and who's behind, and just go.

"The competitive part of me is really there," she concedes. "A lot of champions have been running dogs for 25 years and have 20 Iditaods under their belts and are 45 to 50 [years old]. And here's Aliy Zirkle, just inching into 30, coming up behind them. I think there's an itch for me to come in there.…I really think I can do it."