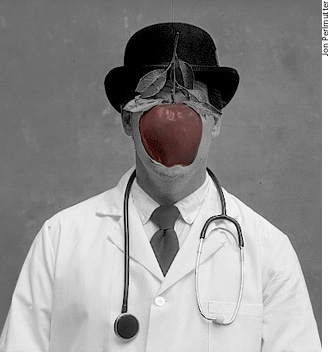

In Sickness & In Health

In America, when we think about sickness and health, one of the first

things that comes to mind is science. Some of the world’s frontline

research—inquiries that hold the promise of treatments for deadly

diseases—is underway in the laboratories of the School of Arts and

Sciences.

Using powerful computational tools in conjunction with more traditional laboratory methods, biology professor David Roos parses the genes and proteins of the single-cell parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The work of the Roos group is widely recognized for having developed Toxoplasma as a genetic model, a guinea pig for studying other protozoan parasites, including the cell-invading bug that causes malaria. The World Health Organization lists malaria as one of the world’s “Big Three” infectious diseases. Roos’ discoveries have led to new drugs, now undergoing clinical trials, for slaying the malaria parasite.

Nathan Sivin, a historian of Chinese science and medicine, points out that sickness and health aren’t only about biology. “People have the same body all over the world,” he affirms. “But to say that all are concerned with the same body is to lose sight of how differently physicians and other curers at various times and in various societies have perceived the body and explained sickness and health. . . . Every culture has its own way of thinking about [the body] and ways of using resources that happen to be present to treat it.”

Money is, perhaps, a quintessentially American theme that comes up when

thinking about sickness and health. Alumnus Mitchell

Blutt, a partner with a New York private equity firm, makes note of

Americans’ “schizophrenia” when it comes to matters of

money and medicine. We want the best and the most health care, he says,

but we’re not willing to accept the tax increases needed to pay for

it.

Emerita sociology professor Renée Fox calls attention to another American trait: the can-do optimism that put American surgeons at the forefront of organ transplantation. She cautions that unwillingness to face the limits of “rescue-oriented” medical intervention, which views death as an enemy, quite often leads to greater suffering. Americans, it seems, acknowledge the certainty of neither death nor taxes.

“Medicine,” Fox goes on to say, “deals with every stage of the human life cycle—from our coming in, to our going out.” It summons up from the depths of our lives the troubling and unanswerable “whys” about suffering and death. Like religion, medicine touches profoundly on the human predicament: birth, growth, maturity, and decay—the allotted time each of us has to draw breath in sickness and in health. ‘Til death do us part.