A gerbil is a "Doggie."

Confusion of length and number:

A A A A

B B B

C C C C C C C C C C C C

D D D D D D D D D

Understanding of area (Wertheimer):

--------------------- / / Area = base x height / / --------------------- --------------- / \ Area = base x height ? / \ ---------------------

Examples relevant to policy:

The death rate for unvaccinated children is 10 out of 10,000 children under 3. These children die from the flu.

The death rate for vaccinated children is 5 out of 10,000 children under 3. These children die from the vaccine.

If you had a child under 3, should you vaccinate your child? 2 (Spranca, Minsk, and Baron, 1991). John, the best tennis player at a club, wound up playing the final of the club's tournament against Ivan Lendl (then ranked first in the world). John knew that Ivan was allergic to cayenne pepper and that the salad dressing in the club restaurant contained it. When John went to dinner with Ivan the night before the final, he planned to recommend the house dressing to Ivan, hoping that Ivan would get a bit sick and lose the match. In one ending to the story, John recommended the dressing. In the other, Ivan ordered the dressing himself just before John was about to recommend it, and John, of course, said nothing.

Vaccines and other drugs (DPT, polio)

Neglect of world poverty

The questions you have just answered concern the distinction between actions and omissions. We would like you now to reconsider your answers. First, read this page and think about it. Then answer the questions again on the next page. ...When we make a decision that affects mainly other people, we should try to look at it from their point of view. What matters to them, in these two cases, is whether they live or die.

In the vaccination case, what matters is the probability of death. If you were the child, and if you could understand the situation, you would certainly prefer the lower probability of death. It would not matter to you how the probability came about.

In cases like these, you have the choice, and your choice affects what happens. It does not matter what would happen if you were not there. You are there. You must compare the effect of one option with the effect of the other. Whichever option you choose, you had a choice of taking the other option.

If the main effect of your choice is on others, shouldn't you choose the option that is least bad for them?

* Refusing to treat someone who needs a kidney transplant because

he or she cannot afford it.

* Fishing in a way that leads to the painful death of dolphins.

* Destruction of natural forests by human activity, resulting in

the extinction of plant and animal species forever.

* Punishing people for expressing nonviolent political

opinions.

* Letting a family sell their daughter in a bride auction (that

is, the daughter becomes the bride of the highest bidder).

Moral (universal, objective). This would be wrong even in a country where everyone thought it was not wrong.

People have an obligation to try to stop this even if they think they do not.

Denial. In the real world, there is nothing we can gain by allowing this to happen.

Anger. I get angry when I think about this.

Agent relative. You have an option to buy stock in a company that does this. Another buyer will buy the stock if you don't. This is the last share of a special offer, so your decision does not affect the price of the stock. Is it wrong for you to buy the stock?

Causing the extinction of fish species.

This is acceptable if it saves people enough money.

This is acceptable if it leads to some sort of benefits (money or

something else) that are great enough.

This is not acceptable no matter how great the benefits.

| Threshold | Zeros | |||

| PV | no PV | PV | no PV | |

| Exp. 1 | .20 | .43 | .28 | .04 |

| Exp. 2 | .38 | .60 | .07 | .01 |

Value elicitation

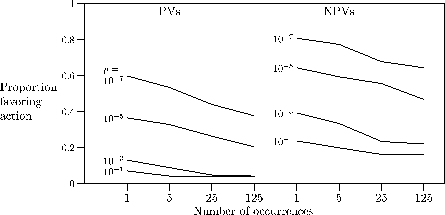

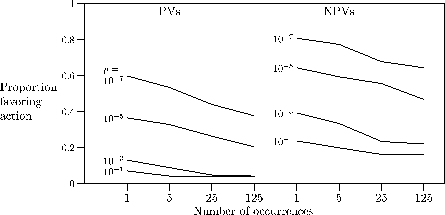

Probabilistic harm

Small harm

Conclusion: PVs are strong opinions, weakly held.

Would you cut back?

Would cutting back "increase your income from fishing over the

next few years?" (29% said yes)

"If I cut back now, I would not have to face the fear of running out of fish to sell and I could keep staying in business for a longer time and everyone else would also benefit." "Because if we cut back, there will be more fish for 4 years of 3 years so it would be a greater profit."

The self-interest illusion can encourage cooperation.

But those who sacrifice on behalf of others like themselves may be more prone to the self-interest illusion. They think, roughly, ``My cooperation helps people who are X. I am X. Therefore it helps me.'' This kind of reasoning is easier to engage in when X represents a particular group than when it represents people in general.

Parochialism (Bornstein and Ben-Yossef, 1994; Schwartz-Shea and Simmons,1990, 1991): A model of real-world conflict and rent seeking (Krueger,1974).

A puzzle for public choice theory, which assumes that people sacrifice their self-interest on behalf of a group.

Done on web. N=84. Real money.

This game has two groups. Each group has three subjects. Each member of your group will receive a bonus based on the number of your group members who contribute and on the number of the other group members who contriubte.This condition (and another two-group condition without the tabular presentation) were compared to one-group conditions in which the minimum payoff to contributors was $1 or $2, this approximating the payoff in the two-group condition with a moderate number of contributors in the other group.The endowment is $1.50 [or $2.00 or $2.50].

The bonuses will be distributed as follows:

Contributors Contributors Bonus for each Bonus for each in your group in other group in your group in other group 3 0 $6 $0 2 0 $5 $1 1 0 $4 $2 0 0 $3 $3 3 1 $5 $1 2 1 $4 $2 1 1 $3 $3 0 1 $2 $4 3 2 $4 $2 2 2 $3 $3 1 2 $2 $4 0 2 $1 $5 3 3 $3 $3 2 3 $2 $4 1 3 $1 $5 0 3 $0 $6

All items ended with the following statement and questions (with additional spaces for comments, and a test question to insure attention):

Do you contribute your endowment now? (y=yes, n=no)Is it your personal self-interest to contribute your endowment? (y=yes, n=no, d=don't know or not sure)

Do you expect more money if you contribute your endowment than if you do not? (y=yes, n=no, d=don't know or not sure)

Subjects did contribute more in the two-group condition than in the one-group condition (82% vs. 73%), replicating the parochialism effect.

More importantly, the parochialism effect for contributing was highly correlated across subjects with the parochialism effects for Self-interest and More-money (r = .75 for each correlation, p = .0000). In other words, those subjects who showed a greater parochialism effect for contributing showed a greater self-interest illusion when the gain for their group was a loss for the other group.

|

A Time to Join YOUR VOICE COUNTS! Sometimes you may think that the voice of an individual doesn't count for much. ``What does it matter if I join or not?'' While your membership in the Guild is confidential, management is very aware of the total number of members, so every member counts. A union with more members can do more. It's as simple as that. ... There's more protection for our jobs, our salaries, and our benefits. Check out what the Guild won-including 9% wage increases-what it lost, and what it protected you from when the current contract was negotiated. |

The response to the More-money question was an error in arithmetic. When this error is corrected, parochialism reduces (in a second experiment).

It may be possible, through reason, to understand the arbitrariness or group boundaries.

We might think of actions as potentially affecting the self, the group, and the world. In the situations of interest here, some action helps the group but hurts both the self and the world.

All these results can be seen as resulting from a kind of overgeneralization.

Too few principles? Or too many?

Biases survive reflection. But the normative standard can still be defended.

The kinds of thinking I have described may actually play a causal role in determining policy outcomes. Small effect, but adds up.

If we are disturbed about the outcomes, we might consider changing the judgments that support them.

Reason for optimism: these judgments are labile. Trying to change them may be cost-effective, relative to the alternatives.