Colin Twomey

Data Driven Discovery Initiative

University of Pennsylvania

About

I'm the executive director of the Data Driven Discovery Initiative — the University of Pennsylvania's hub for data science research and education in the School of Arts & Sciences. I'm also the founder and director of the University Atlas project (uAtlas) — an effort to map the research world at Penn and beyond (read more in Penn Today).

I started at Penn as a MindCORE Postdoctoral Research Fellow working with Joshua Plotkin on inference for cultural evolution. Prior to Penn, I did my Ph.D. on collective behavior at Princeton University with Iain Couzin. As an undergraduate, I studied computer science as a Goldwater Scholar at Colgate University and worked on combinatorial optimization as a Fulbright Fellow at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. In industry I've worked as a software developer at Sun Microsystems and as a data science consultant for the World Bank and agtech startup Arable Labs.

Contact

- crtwomey{at}sas{dot}upenn{dot}edu

-

Colin Twomey

Data Driven Discovery Initiative

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA 19103

Research

What are the natural algorithms underlying collective behaviors? How do persistent patterns and properties of a group emerge from the repeated interactions of its constituents?

The collective motion of a fish school isn't determined by any one leader, but emerges from the attraction, repulsion, and alignment of individuals throughout the group. Common to all animals is the use of sensory systems to make informed decisions, and in my research I investigate in particular the role that sensory systems play in shaping and constraining collective behavior.

-

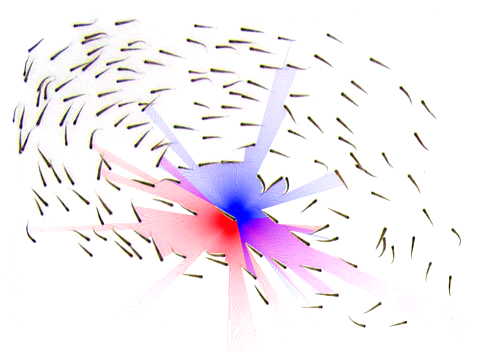

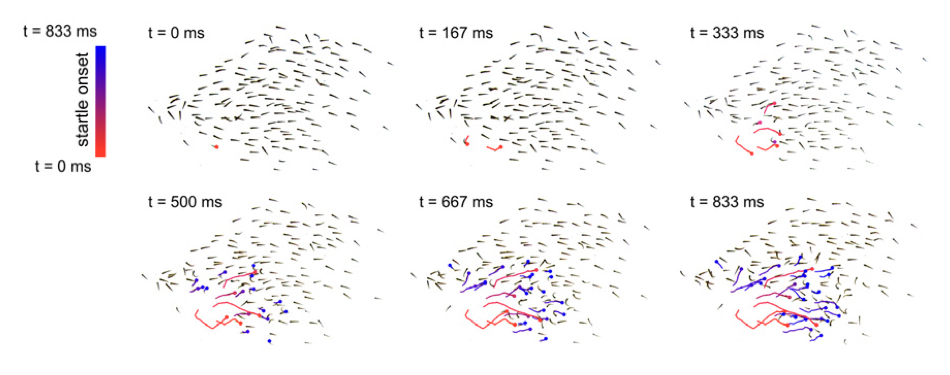

Behavioral cascades

Startle responses in fish schools are critical for avoiding predation. A single individual startling can induce a wave of startle responses across a group. What sensory information, social and non-social, makes an individual more or less likely to startle in response to the startle of a neighbor?

Answering this question allows us to uncover the network of sensory information in a group, and to say when and how information may propagate through a school at any given moment.

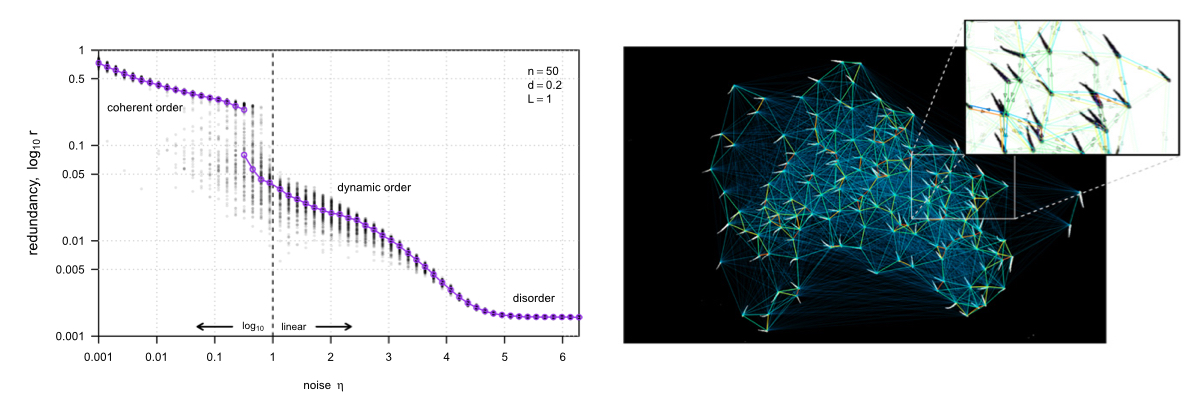

Within-group structure

What are the right levels of organization to look at to understand collective behavior? Collective properties at the group level may not always be best explained by interactions at the individual level. Instead, we should ask whether or not there may be a simpler, mesoscale descriptions that allow strongly interacting components to be considered as a unit, and investigate the weak but non-negligible couplings between these intermediate-scale and possibly ephemeral subgroups.

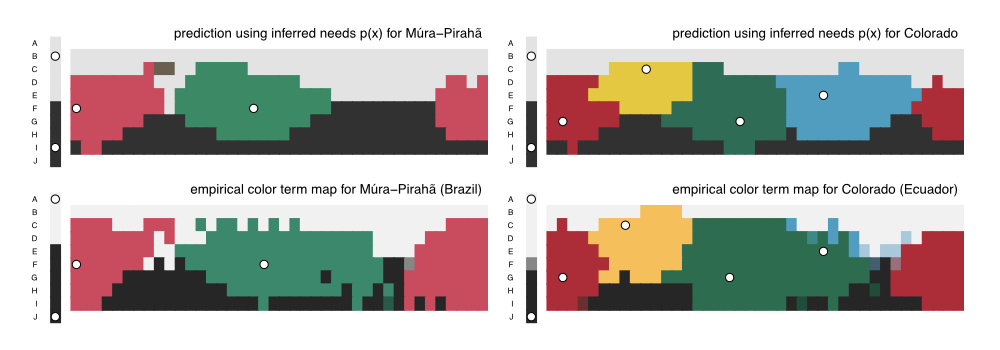

Collective cognition

Consensus decisions are a common feature of groups in the animal world. In humans, the words we use to communicate with others are themselves a product of a collective consensus process. Despite the apparent flexibility of such a process, there are surprising instances in which vocabularies of independent linguistic origin converge to very similar representations. The most famous of these are words for describing color. While languages vary in the number of words and the ways in which these words partition the space of visible light, they do so in a remarkably constrained way.

Why should there so often be simple and intelligible mappings between the color words of completely unrelated languages? In my work, I investigate how this may arise from a collective consensus process that is fundamentally constrained by the shared physiology of our perception of color. This has implications for how other animal groups may arrive at shared, learned representations of stimuli, even in the absence of a shared vocabulary.

Code

- twomey2024: Reproducible code and data supplementary information for Twomey et al. 2024: History contrains the evolution of efficient color naming, enabling historical inference. (GPL v3, R)

- twomey2021: Reproducible code and data supplementary information for Twomey et al. 2021: What we talk about when we talk about colors. Provides a reference implementation of the algorithm for inferring communicative need from a rate-distortion efficient vocabulary. (GPL v3, R)

- sscs: An implementation of the partitioning algorithm introduced in Twomey et al. "Searching for structure in collective systems", provided as an R package. (GPL v3, R and C++)

- paws: An implementation of the partitioning algorithm introduced in Jones et al. "A machine-vision approach for automated pain measurement at millisecond timescales", provided as an R package. (GPL v3, R)

- fovea: Body-pose and field-of-view estimation for fish schools. (GPL v3, C++, depends on OpenCV; coming soon)

- fieldtracker: Tracking software developed for coral-reef fish school field data used in Hein et al. (2018). (BSD-3, python, depends on OpenCV)

- ftrack: Fast tracking for individual or a few well separated fish. This has been superseded by Hai Shan Wu's tracking software for large groups, but can still be useful for quickly tracking single individuals in individual choice experiments. (GPL v3, C++, depends on OpenCV; coming soon)

Publications

- Twomey, C.R., Brainard, D.H. & Plotkin, J.B. (2024) History constrains the evolution of efficient color naming, enabling historical inference. PNAS 121(10):e2313603121.

- Bohic, M., Pattison, L.A., Jhumka, Z.A., Rossi, H., Thackray, J.K., Ricci, M., Mossazghi, N., Foster, W., Ogundare, S., Twomey, C.R., Hilton, H., Arnold, J., Tischfield, M.A., Yttri, E.A., Smith, E.S., Abdus-Saboor, I. & Abraira, V.E. (2023) Mapping the neuroethological signatures of pain, analgesia and recovery in mice. Neuron 111(18):2811-2830.

- Sridhar, V.H., Davidson, J.D., Twomey, C.R., Sosna, M.M.G., Nagy, M., & Couzin, I.D. (2023) Inferring social influence in animal groups across multiple timescales. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 378(1874):20220062.

- Poel, W., Daniels, B.C., Sosna, M.M.G., Twomey, C.R., Leblanc, S.P., Couzin, I.D., and Romanczuk, P. (2022) Subcritical escape waves in schooling fish. Science Advances 8(25):eabm6385.

- Jolle, J.W., Sosna, M.M.G., Mazué, G.P.F., Twomey, C.R., Bak-Coleman, J., Rubenstein, D.I., and Couzin, I.D. (2022) Both prey and predator features predict the individual predation risk and survival of schooling prey. eLife 11:e76344.

- Twomey, C.R., Roberts, G., Brainard, D., and Plotkin, J.B. (2021) What we talk about when we talk about colors. PNAS 118(39):e2109237118.

- Davidson, J.D., Sosna, M.M.G., Twomey, C.R., Sridhar, V.H., Leblanc, S.P., and Couzin, I.D. (2021) Collective detection based on visual information in animal groups. J. R. Soc. Interface 18:20210142.

- Devereux, H.L., Twomey, C.R., Turner, M.S., and Thutupalli, S. (2021) Whirligig beetles as corralled active Brownian particles. J. R. Soc. Interface 18:20210114.

- Jones, J.M., Foster, W., Twomey, C.R.*, Burdge, J., Ahmed, O.M., Pereira, T.D., Wojick, J.A., Corder, G., Plotkin, J.B., and Abdus-Saboor, I. (2020) A machine-vision approach for automated pain measurement at millisecond timescales. eLife 2020;9:e57258.

- Twomey, C.R., Hartnett, A.T., Grobis, M.M., and Romanczuk, P. (2020) Searching for structure in collective systems. Theory in Biosciences (special issue on quantifying collectivity) https://doi.org/10.1007/s12064-020-00311-9.

- Sosna, M.M.G., Twomey, C.R., Bak-Coleman, J. Poel, W., Daniels, B.C., Romanczuk, P., and Couzin, I.D. (2019) Individual and collective encoding of risk in animal groups. PNAS 116(41):20556-20561.

- Hein, A.M., Gil, M.A., Twomey, C.R., Couzin, I.D., and Levin, S.A. (2018) Conserved behavioral circuits govern high-speed decision-making in wild fish shoals. PNAS 115(48):12224-12228.

- Rosenthal, S.B., Twomey, C.R.*, Wu, H.S., and Couzin, I.D. (2015) Revealing the hidden networks of interaction in animal groups allows prediction of complex behavioral contagion. PNAS 112(15):4690-4695.

- Strandburg-Peshkin, A., Twomey, C.R., Bode, N.W.F., Kao, A.B., Katz, Y., Ioannou, C.C., Rosenthal, S.B., Torney, C.J., Wu, H.S., Levin, S.A., and Couzin, I.D. (2013) Visual sensory networks and effective information transfer in animal groups. Current Biology 23(17):pR709-R711.

- Twomey, C.*, Stutzle, T., Dorigo, M., Manfrin, M., and Birattari, M. (2010) An analysis of communication policies for homogenous multi-colony ACO algorithms. Information Sciences 180(12):2390-2404. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2010.02.017.

- Frey, F., Delph, D.F., Dinneen, B., and Twomey, C. (2007) Evolution of sexually dimorphic flower production under sexual, fertility, and viability selection. Evolutionary Ecology Research 9:1-19.