The moment was pivotal for both mother and son, because it was one of the first times that Maurice was confident enough to speak Spanish outside his fourth-gra de classroom. And Ms. Evans had the opportunity to witness firsthand the benefits of her son's school's relatively uncommon language instruction program, known as dual language.

"All of a sudden I was telling the driver in Spanish how to get from Stern's department store to our apartment in Sugar Hill," Maurice, who is African-American, recalled recently during an interview at the school. "Now, I help my mom and neighbors at the bodega when they need a translator."

Ever since first grade, Maurice, a student at Amistad Dual Language School, a public elementary school in Inwood, has spent one day learning his subjects in Spanish and the next in English, alternating throughout the year. The dual-language program, which has 180 students, deli berately mixes English-speaking and Hispanic students in equal numbers so they can learn from each other.

Dual language is not a traditional bilingual program, in which students learn English for a single period a day while studying subjects like mathematics, science and social studies in their native languages. It is an alternative program that encourages foreign-born students to view their native tongues as something to share and treasure rather than shed. Traditional bilingual programs have als o come under attack because, critics say, some immigrant students learn too little English and often spend their entire school careers without mastering English.

By contrast, in dual-language classes, students — English and foreign born — have bee n found to learn their second language in a relatively short time, its proponents say. At the same time, the every-other-day emphasis on English makes clear to immigrant students that its acquisition is crucial. For English-speaking students, it helps the m acquire a second language with relative ease and it places equal value on languages and heritages, which allows students to explore different cultures from an early age.

Schools Chancellor Harold O. Levy has proposed increasing the number of dua l-language programs in the city from 60 to 80 under a plan to overhaul bilingual education. The Board of Education will hear public comment on the proposal at a public hearing at its headquarters tonight and is to vote on it next month.

"The goal of dual-language models is to promote long-term literacy in both the native language and English for both groups of students," Mr. Levy said. "This is an important option for parents who value literacy in more than one language, whether for cultural, eco nomic or educational reasons."

Though 23 states with large Hispanic populations have adopted dual- language programs at 248 schools, there are also some programs in Chinese and French, according to the Center for Applied Linguistics in Washington .

Luisa Costa Garro, a linguist and professor of education at the Bank Street College of Education in Manhattan, said that unlike traditional bilingual-education programs, dual- language classes allow children to break away from learning languages in a vacuum. They learn social studies, math, science and other subjects in a second language with such consistency that few students struggle, she said. Maurice and his fourth- grade classmates, for example, are preparing for the state's fourth- grade r eading test mostly in English, said Elia Castro, director of Amistad.

Dual-language programs are not without their skeptics.

Ron K. Unz, the Silicon Valley entrepreneur who helped finance and organize the initiative that all but eliminate d bilingual education in California almost two years ago, said dual-language programs are so scarce because they require such specialized teachers. Given their scarcity, he said, it is difficult to measure whether they would work on a large scale, and the re is little comprehensive research to show that they benefit immigrant children.

Some supporters of traditional bilingual education contend that there is little difference on test scores between bilingual and dual-language students. However, ther e is some research at schools in cities like Cambridge, Mass., that indicates that some immigrant students in dual- language programs outperform those in traditional bilingual programs on standardized tests.

Charles L. Glenn, a professor of educat ion at Boston University, who for 21 years directed urban education for the state of Massachusetts, sent five of his seven children through dual-language programs in Boston. While he is a champion of the programs, he said that from his experience, English -speaking children do not truly become bilingual.

"They become much more proficient in Spanish than children in a Spanish-language class," he said, "but they do not become bilingual. On the playground, you will hear English being used. I don't thi nk you can prevent that."

Amistad, a four-year-old elementary school, is one of dozens of small dual-language schools that have opened in the city in recent years. Students must apply and they are selected by lottery.

On a recent English d ay in a second-grade classroom, voices rose and fell as 28 students sat at child- sized rectangular tables drawing pictures of scenes from a story about two geese seeking shelter from an impending storm.

Fluorescent lights danced off yellow- pain ted cinder-block walls. The classroom library was lined with a cornucopia of Spanish and English books, including "No Me Quiero Bañar," a book about a little boy who does not want to take a bath, and "Los 500 Sombreros de Bartolomé Cubbins," by Dr. Seuss.

Three 7-year-olds worked at the same table: Emmanuel Cavallini, Carolina Santos and Mabel Duval. Emmanuel and Carolina spoke English easily, but Mabel, whose native language is Spanish, spoke hesitantly. When asked what she was working on, Mabel said she had just read a story about ducks.

"No, un ganso," Emmanuel said, giving her the Spanish translation for a goose, the kind of help that is encouraged.

"A goose," Mabel said, blushing.

"Mabel knows a lot, but she is so shy that she gets nervous and reverts to Spanish," said her teacher, Rosa M. Garcia.

The benefits of the program seem clear to Spanish-speaking parents.

Xiomara Cavallini, a beautician from Milan, Italy, who is fluent in both Italian and Span ish, said that she and her husband, Marcos, who is Italian, enrolled Emmanuel in Amistad, on Broadway between Academy Street and 204th Street, because they wanted to preserve his ability to speak Spanish and Italian.

Now, Emmanuel, who enrolled a t Amistad in kindergarten three years ago speaking only Spanish and Italian, is helping his parents learn English.

"So many times when young children begin to learn English, they forget the native languages of their parents," said Mrs. Cavallini, who said she and her husband speak Spanish and Italian at home. "This way, they get to keep it."

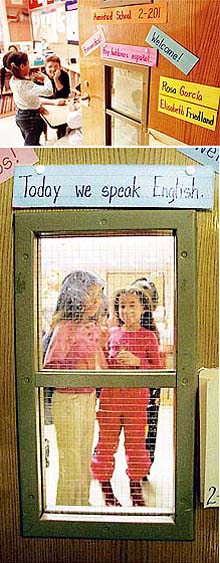

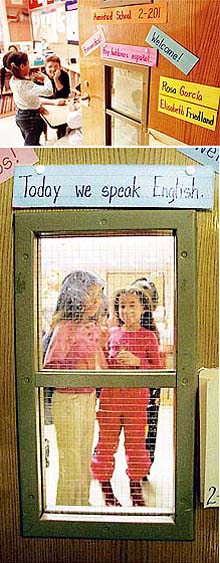

| Photographs by Ruby Washington/The New York Times |

| At the Amistad Dual Language School in Upper Manhattan, students learn all subjects in Spanish one day, top, and in English the next, above. |