The New Yorker, 7/14/97, pg. 38

THE CULTURE INDUSTRY

THE ORIGIN OF ALIEN SPECIES

There are precisely six types of space creature out there---and it's all on film.

BY KURT ANDERSEN

D

uring the past several years, evolutionary biologists have proved that the disparate creatures of our planet are, at a fundamental genetic level, very similar to one another. The genes that differentiate the top and the bottom of a bug, for instance, are the same ones that differentiate our fronts from our backs. According to the paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, this new understanding is among "the most stunning evolutionary discoveries of the decade," and is clearly "a dominant theme in evolution."The same law applies, it appears, to the extraterrestrial creatures that come out of Hollywood. As is true of biological evolution, the evolution of movie aliens is constrained by a limited range of modes and materials: skeletons are aluminum, steel, or fibreglass; skins are foam rubber, polyurethane, silicone, or gels. In the evolutionary pseudobiology of the cinema, memes, rather than genes, circumscribe the forms that a new alien creature can take. "The process of designing aliens always take s you back to variations on a theme," Laurie MacDonald, the coproducer of the new film "Men in Black," told me. "They all look similar." There may be more than one way to skin an extraterrestrial, in other words, but not a lot more.

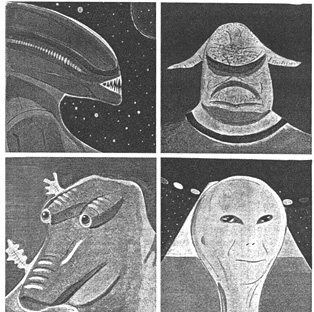

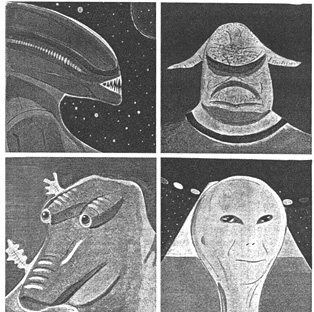

Is the current alien mania in films ("Men in Black," 'The Fifth Element," "Contact"), on television ("The X-Files," "3rd Rock from the Sun"), and in the news (Heaven's Gate, Roswell reminiscences) some kooky by-product of the end of the Cold War? Or can it be an epiphenomenon of the turn of the millennium? Thats what commentators have been asking lately. Perhaps the more interesting question is: Why are so many of the new movie aliens so. .. gooey? A preliminary taxonomy indicates that Hollywood aliens may be classified into six distinct phyla.

Type One

, more or less normal-looking people, includes most aliens in episodic network television, from the original "Star Trek" to "3rd Rock from the Sun." A subcategory is the alien lollapalooza, usually a blonde: Zsa Zsa Gabor in 'The Queen of Outer Space" (1958), say, or Natasha Henstridge, the star of "Species" (1995). In many instances, of course, aliens assume human form only in order to charm Earthlings (as in the forthcoming Jodie Foster movie, "Contact") or to keep below-the-line production costs under control.Type Two consists of hulking humanoids with enormous bald heads, which are (a) anatomically expressionist, (b) faux leprous, or (c) shaped like a chefs toque. Originally a product of suspicious nineteen-fifties anti-intellectualism---giant skull equals genius equals Communist---Type Twos include the (balding) Klingons and Ferengi from "Star Trek," the diva in 'The Fifth Element," and, in overtly parodic mode, the Coneheads and the exposed-brain aliens in "Mars Attacks" (1996).

Type Three, which has emerged only during the past few decades, is the modern classic: the small, gray, hairless, chinless, big-eyed waif, resembling the woman from Munch's 'The Scream" on antidepressants or a member of a children's mime group. These wan, innocent, naked creatures appeared during the Woodstock era and after--and, tellingly, supplanted the scheming, sinister, aggressively superhuman aliens typical of the anti-Communist fifties. The definitive portrayal appeared in Steven Spielberg's "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" (1977), but those aliens surely bear some cinemagnetic relation to the space fetus at the end of "2001" (1967) and to the aliens in 'The X-Files," even down to the portentous backlighting.

As it happens, the great majority of "real" aliens today are also Type Threes, including the ones who abducted Whitley Streiber in his book "Communion: A True Story," and the ones who performed experiments on the abductees treated by the Harvard Medical School professor John Mack during the past decade. Is it unfair to assume that suggestible people began seeing Spielbergian aliens in real life during the eighties as a result of having seen the aliens in "Close Encounters" during the late seventies? No more unfair than to assume that it was only after McCaulay Culkin pumped his arm triumphantly and said 'Yesss!" in "Home Alone" (1990) that millions of American eleven-year-olds acquired the habit of pumping an arm triumphantly and saying "Yesss!"

Hollywood Extraterrestrial Type Four is the comic-relief plus toy. The tiny, furry tribbles; in the original "Star Trek" series may have been the first appearance of this type. Other instances include the title character in "Alf" and most of the memorable secondary characters in "Star Wars," such as Chewbacca and the Ewoks. A prominent Type Four subgroup is the evil, rotund comic-relief plush toy, such as the creatures in "Gremlins" (1984) and the churlish bovine/porcine warriors in both "Return of the Jedi" and "The Fifth Element." It seems no accident that Type Four aliens, clownish but winning, achieved their peak of popularity at the very moment we were giving a landslide reelection to Ronald Reagan, our clownish but winning plush-toy President.

Type Five is the swamp creature---reptiles and amphibians who walk upright. This was a standard form of the fifties, and reemerged with a vengeance, like just about every other fifties cultural artifact, during the eighties. The nicer aliens of this type are apt to be more amphibian than reptilian. The major examples---E.T. (1982) and Yoda (1983)---both arguably have strains of Type Three (big eyes) and Type Four (tactile, seriocomic cuteness) as well. The evolutionary. semiotics seem straightforward: frogs and turtles are homely but cute and unthreatening. Conversely, snakes and lizards are scary, so reptilian extraterrestrials are bad, notable recent examples being the reptilian queen alien in "Aliens" (1986) and the man-killing lizard girl Sit in "Species." Sil and the creatures in, the original, 1979 "Alien" were designed by the Swiss artist H. R. Giger, but the director and creature designer of its sequel "Aliens" were James Cameron and Stan Winston, respectively. "Jim Cameron had the concept that there would be a queen," Winston told me. "He'd done a painting of her. The big change from that first concept was an added joint to the leg that gave her feet the look of high-heeled shoes. This was a queen. This was a bitch." Antifeminist backlash as a Hollywood-alien design parameter seems not to have caught on, but the lizardy, slightly buglike "Aliens" queen undoubtedly led to the lizardy, slightly buglike "Independence Day" (1996) extraterrestrials; and to the lizardy aliens in Robin Castes novel and TV miniseries "Invasion." (Some ostensible real-life abductees, according to C. D. B. Bryan's 1995 book "Close Encounters of the Fourth Kind," have reported experiences with menacing, six to-eight-foot-tall reptilian aliens.)

Hollywood Extraterrestrial Type Six consists of hypertrophied arthropods, or, in lay terms, really, really big shellfish and insects. Again, as with the reptilian aliens they sometimes resemble, the genesis seems clear: bugs are gross. The title character in "Predator" (1987) was a hybrid that Stan Winston, its creator, describes as a "Rastafarian insectoid-humanoid alien." The movie's producer, Joel Silver, suggested the Rasta notion, and James Cameron, who wasn't even working on the picture, inspired the rest. "Jim and I were on a flight to Japan to speak at a symposium on creatures in movies, " Winston told me. "I remember drawing my first sketches on the plane, and he looked over my shoulder and said, 'I'd like to see a creature with mandibles.' Today, a decade later, giant alien insects are everywhere, threatening to destroy mankind not only in "Men in Black"twelve-foot-tall neo-cockroach) but in next falls "Starship Troopers" (hordes of ten-foot-tall grasshoppers). An emerging alien metatype that blurs the categories is the morphing extraterrestrial, the creature who visibly changes on-screen from human being to bug or bug to lizard. The morphing extraterrestrial is almost wholly a function of technology-in this case, computer-generated-imagery, The other unmistakable trend in aliens is of a piece with -gross-out explicitness in pop culture generally. Extraterrestrials today tend to be wet, the glycerine sheen variously suggesting evisceration, birth, mucus, dangerous bodily fluids, otherworldly goo. "Slime?" Stan Winston said when I asked if he thought he had helped usher in the current Wet Era with his work on "Aliens." "I would say yes, there is some thing visceral that comes from seeing drool---maybe you relate it to a rabid animal."

"MEN IN BLACK," which posits Earth as an intergalactic Switzerland (and Earthlings like Elvis Presley as incognito extraterrestrials; in exile), represents an alien-morphology apotheosis. For the first time in the history of film, every one of the six main alien types is represented. And the movie is fill of alien goo. Indeed, "Men in Black," doesn't seem to want its extraterrestrials to look too original: it intends to be familiar in a hep "Nick at Night" fashion, and assembles a pastiche of extraterrestrial archetypes to do its postmodern business.

Laurie MacDonald coproduced the film with her husband, Walter Parkes. 'We always knew Edgar was going to be a bug," Parkes told me, speaking about their main alien villain. "The first design looked too much Eke our house cat," MacDonald recalled.

"We moved it scarier," Parkes said. They also moved it away from the design of the "Independence Day" aliens. "When we heard that their main alien was going to be a lot like ours, there was some substantial redesigning of Edgar," he explained. "If you look at Edgar now, he has that protruding Jaw and those enormous teeth. But we didn't want to go too far into the territory of 'Alien.' "

Stan Winston's aliens have been more imitated than imitative, but even he admitted, "It's impossible not to be influenced by things you have experienced in the past." His other major conclusion about creating movie aliens is that the creatures have to be able to express feelings. "You must relate to it with something you can relate emotion to."

"Human form is an interesting issue in this," Walter Parkes said about the challenge of designing aliens for "Men in Black." "On the one hand, you want to be able to relate to these creatures, so you want some semblance of human form. But you don't want the audience to say, 'It's just a man in a suit.'" Steven Spielberg, as the film's executive producer, also helped decide how the aliens in "Men in Black" would look. "Steven's main note," Parkes told me, "tended to be that the alien faces should somewhere and somehow reflect human structure." He paused. "And that's because, of course, he's an alien himself."