Less than 1 km, a few paved stairs and one steep dirt path; a moderately infirm person would need a steadying hand. Closed-toe shoes are recommended. (No high heels!)

Gordion is famous as the home of King Midas, a real king who, according to

myth, was cursed with turning all he touched to gold. Gordion is also the

place where Alexander the Great is said to have cut the Gordian knot on his

way to conquer Asia.

The Citadel Mound Circuit is marked by 10 informative signs. Although some of

that information will be repeated here, this tour provides some supplementary

information about vegetation, landscape, and site conservation.

Additional information about landscape history can be obtained from the

Gordion Landscape

Overview, Gordion Historical Landscape,

and Tumulus

MM self-guided tours.

Orientation sign

For best results, follow the route around the excavated area in a counter-clockwise direction. Excavations through Medieval, Roman, Hellenistic, and Phrygian levels reached the buildings you can see today and on this plan of the excavated area. This so-called Phrygian “Destruction Level” dates to about 800 BC. Archaeologists have found spent shells and traces of defensive trenches on the top from the Turkish War of Independence, but the latest settlement on the mound dates to the 14th Century AD.

Turn around!

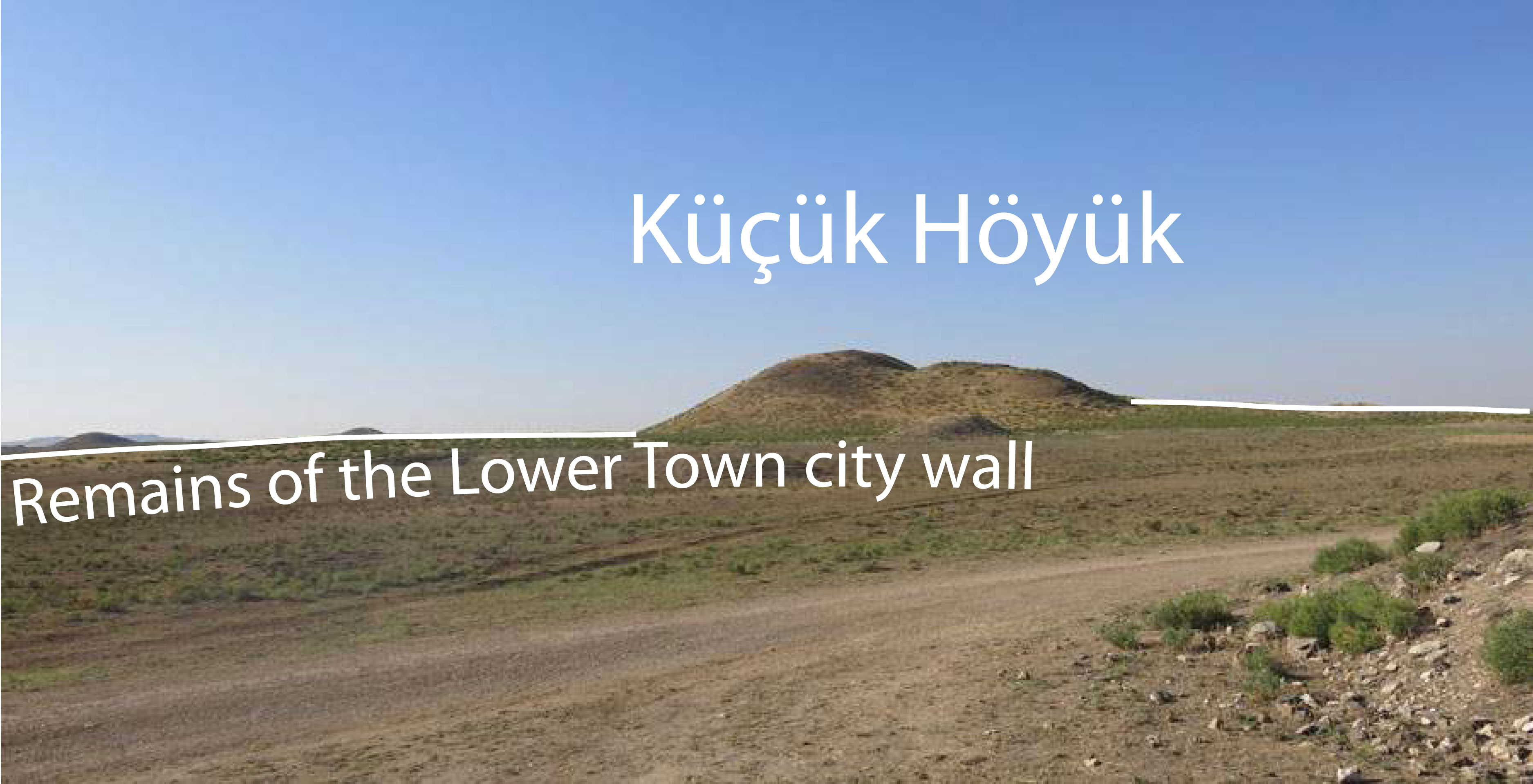

If you turn around, you can see the Küçük Höyük,

which was part of the fortification system. Two low, linear mounds extending

to either side of that mound are the remains of the Lower Town city wall.

Although the walls do not look very impressive today, the Middle Phrygian

(800 BC) surface was several meters below where you are standing. (Do not be

confused by miscellaneous piles of dirt that you may see; they are the

‘backdirt’ from excavations of the 1990s.) Turn back to the sign and proceed

up the ramp or stairs, where on your left you will pass a section of the

Middle Phrygian glacis: the defensive wall of the Citadel mound.

Station 1

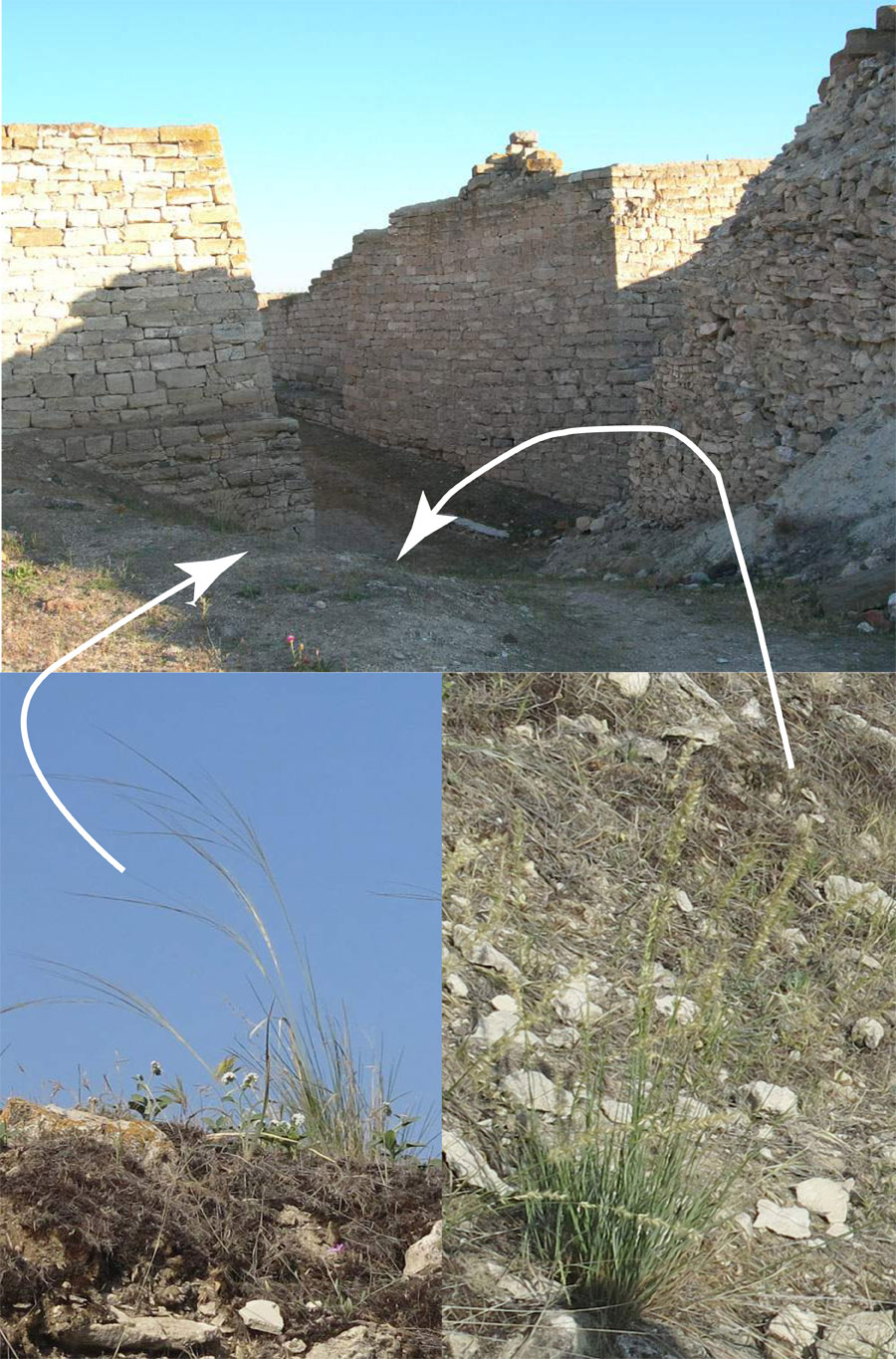

As you face the Early Phrygian Gate (topped by a few large blocks of a

Middle Phrygian structure), off to your right is the rubble fill of the Middle

Phrygian rebuilt gate. If you are here in June-July, on the rubble slope to your

left, you might see feathergrass (Stipa arabica) on the top, and

melic (Melica ciliata at the bottom of the slope. Both are perennial

bunch grasses. Melic also grows on the Middle Phrygian glacis (you just

passed it on your right.)

Station 2

The biggest tumulus is Tumulus MM. A field of smaller tumuli extends to

the right (east). On the far horizon, to the right of MM, you might be able to

make out the Beyceğiz tumulus. Tumulus W is in the direct line of sight

from the Early Phrygian gate; the rebuilt Middle Phrygian gate had a different

orientation.

The most prominent perennial plant on the mound is Syrian rue (Peganum

harmala; üzerlik in Turkish).

For much of the year, the seeds of wall barley (Hordeum

murinum; iyecen in Turkish) will annoyingly get in your socks.

Both of these plants have defenses against herbivores, and so are

characteristic of overgrazed pasture: Syrian rue has chemical defenses in the

form of bitter alkaloids; wall barley has mechanical defenses in the form of

bristly awns.

Station 3

At Station 3 you can see a wall remnant covered with yellow-ocher lichens.

Lichens grow only where the air is clean (so you rarely see them in cities).

As you walk around the site, you will notice that most of the walls, which

have been exposed for over 50 years, support lichens. Lichens grow on bare

rock, and as they grow the stone substrate slowly deteriorates, gradually

turning to soil. Two other issues for wall conservation on open-air

archaeological sites like Gordion are 1) the freeze-thaw cycle during the

winter, which allows rainwater to flow into small crevices; as water turns to

ice, it expands and breaks the rock; 2) rootlets grow into the crevices, and

they, too, can break open the rock.

Station 4

From Station 4 to the east you can see the fields of tumuli closest to the

ancient city. It is likely that the ancient route went along the valley

between the tumulus group on the left and the ones on the ridge to the right,

because that would have made the tumuli appear to be taller and more impressive.

Station 5

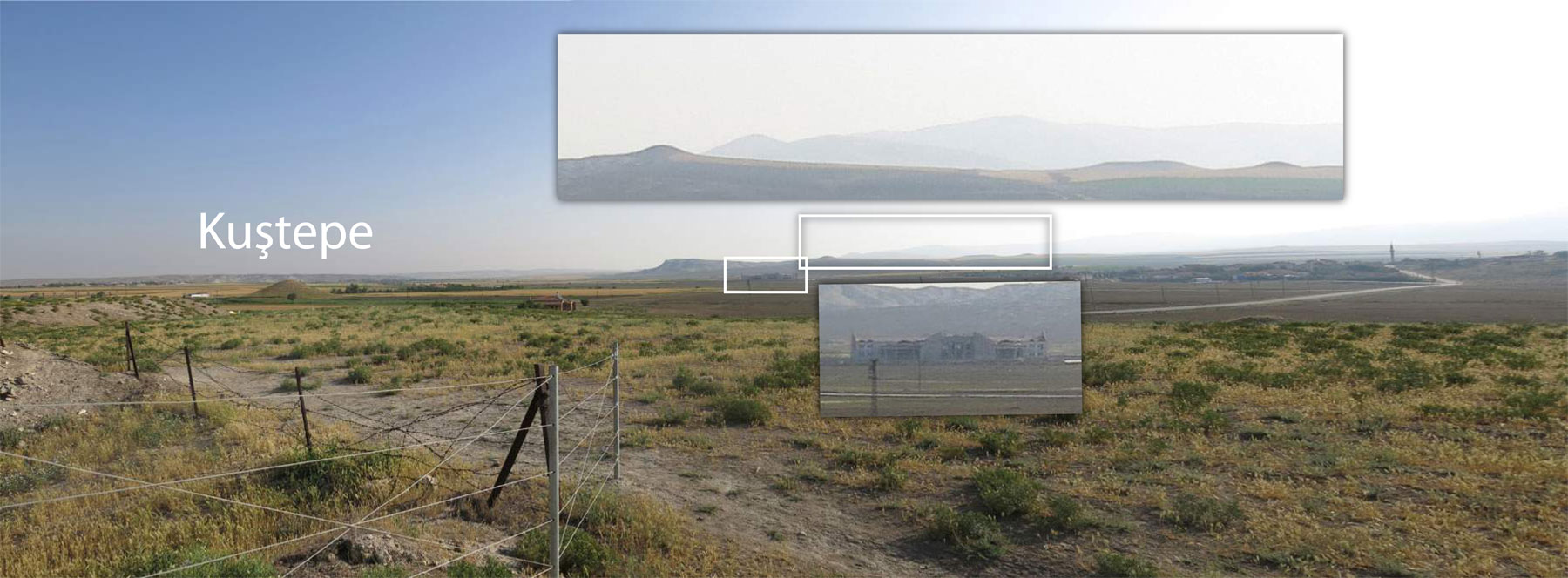

Look left to see the tumulus-like mound (Kuştepe), which was actually

part of the fortification system of the Lower Town. Two tumuli sit on the

horizon line. As a form of ancient conspicuous consumption, tumuli were meant

to be seen; they were a tangible manifestation of the power of the ancient

elite. The hotel that sits in the middle of the valley exemplifies the modern version

of a similar sensibility.

Station 6

For details about the ancient fortifications and history, read the sign.

The Early and Middle Phrygian deposits are physically quite separate, but

chronologically the periods are continuous—the same people who lived through

the great fire went on to level and fill the Early Phrygian structures you see

before you. They then covered the entire area with upwards of 2 meters of

relatively clean fill. Therefore, the people living on the Mound would have

had a nice view of the tumuli that were then under construction on the

ridge to the east. To the south, you might

be able to make out the viaduct that carries the fast train (Hızlı

Tren) between Ankara and Istanbul.

Station 7

As you look directly over the Station 7 sign, you see the Sakarya river, a

garden and old meander line, and a small rise. If the river is low enough, you

might see be able to see lines of stones in the river bed. They are not

natural rapids, but rather remains of walls, for during Middle Phrygian times,

the river ran to the east of the Citadel, not to the west as it does today.

On the natural rise above the present river, the fields are littered with

potsherds and large blocks, characteristic of Middle Phrygian period; limited

excavations in the 1990s confirm that the city grew to its greatest extent

during the Middle Phrygian period. In the mid-distance is the second-tallest

tumulus in the region (after MM).

As you stand at Station 7, look to your right to see the fortification mound

of Kuştepe. Water-loving trees (willow and tamarisk) grow along the

Sakarya River before you. In the distance to the left, you can see another

line of trees that mark the presence of the nearby village of

Kıranharmanı. Kıranharmanı is situated on the Porsuk

River, which is nearly dry, now that most of its water has been extracted for

irrigation upstream. Lying just a few kilometers south of the confluence of

these two rivers, Gordion was well-situated to control trade routes.

Station 8

The village of Yassıhöyük was established in its current

location in the 1920s. Since the 1950s, the site of Gordion has played an

important part in its development: excavation, and increasingly architectural

conservation, provide employment to villagers. The big hotel development on

the valley floor feeds off the romance of the past (while contributing little

towards it).

Station 9

As you look across the excavation area, the terrace buildings, labelled

'TB', are in the foreground. By now you should be quite familiar with Tumulus MM,

the presumed tomb of King Midas’s father. You can see the remains of the Early

Phrygian gate building, which is oriented toward Tumulus W, faces east. (The

photo was taken a bit past Station 9)

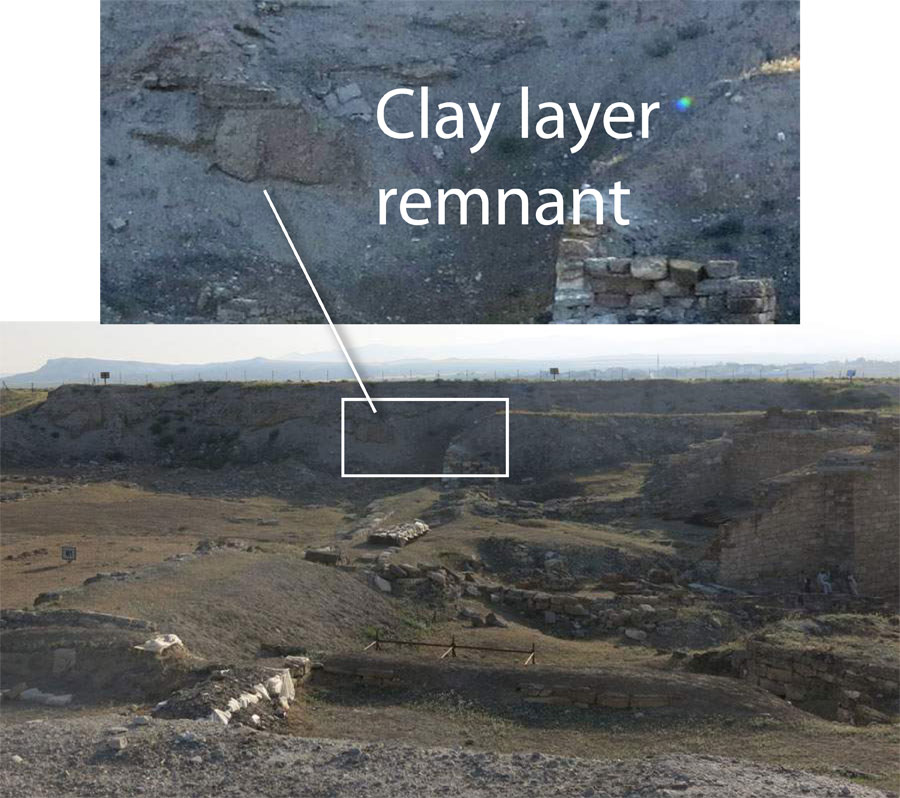

Between Stations 9 and 10

At the 7th or 8th post after Station 9, see if you can spot the remains of the

‘Clay Layer’ that capped the Early Phrygian Citadel, upon which brand new

structures were built. The arrow points to the clay itself, and just above it

is a Middle Phrygian surface (NOTE: an open-air archaeological site is

constantly changing, so you may not be able to see this).

Station 10

There is not much to add to the Station 10 discussion, so you might take

this opportunity to look around once more, to help you remember this magical

landscape. Counter-clockwise from before you: Remains

of the Lower Town fortification wall extend as two linear mounds from the

Küçük Höyük fortress mound. In the distance, the

tumuli on the south ridge lie straight ahead. The main road to the Citadel

separated them from the tumuli to the north, the biggest of which is Tumulus

MM. Tumuli on mountain horizons would have been highly visible symbols of

royal power: the ability to command labor and lay claim to a large territory.

NOTE: I prepared this walking tour in the summer, 2014. It is based on many

publications and conversations over the years with Ayşe Gürsan-Salzmann,

Ben Marsh, Mecit Vural, Mary Voigt, and many other Gordion team members. If

you have any comments or corrections, feel free to contact me at

< nmiller0@sas.upenn.edu >. Fieldwork for this project was funded by the

University of Pennsylvania Museum,

Philadelphia. The views expressed here are mine alone.

Naomi F. Miller, July,

2014

www.sas.upenn.edu/~nmiller0/Tour_citadel.html