Home

Competing Priorities: A blog response to Kashi Dinghra’s article, “Towards science educational spaces as dynamic and coauthored communities of practice.”

The critical factor around which learning

revolves is the provision (or

absence) of access to participation in meaningful science related

activity.

Further, the shared underlying premise is that it is through such

experiences

that students gain access to the opportunities potentially afforded by

a

globalized economy. The general strategy to these ends is the

co-construction

of science-as-practice by (marginalized/immigrant/minority) youth

together with

the teacher who, as cultural broker negotiates between the multiple

worlds

coexisting in the classroom (Dhingra, 2007).

Dhingra’s words should be a

punch-to-the-gut for the

majority of urban high school teachers. With

the constantly increasing pressures of accountability through

standardized

testing and the expanding popularity of district-wide standardized

curricula

(Liu & Fulmer, 2008), even in the educational reform community, the

teacher’s ability to create an environment where the pursuit of science

knowledge is a task shared and co-created with the student is extremely

limited. Subsequently, the students are

denied access to the “globalized economy” and are put at risk of

cultural and

economic marginalization.

In an urban district, where the majority of

the

students are already culturally and/or economically marginalized, this

is a

particular problem. The

result is either a student that works

tirelessly, with little result, or a student who completely withdraws

from the

education environment, either mentally or literally (Ennis &

McCauley, 2002). At my school, this can be

seen in a drop-out

rate that approaches 45%, and students in the “academic” courses that

still get

less than 800 on their SATs, don’t pass their AP exams, and are unable

to earn

Proficient scores on the state assessment, despite all of their efforts. The papers that Dhingra reviews make clear

the necessity of involving the student in the process of creating

his/her

educational experience, but in this era of “accountability” is that

really

possible?

Educational Violence is the

Standard

Dhingra (2007) points out that the response

to a call

for a standardized curriculum is a resorting to either “fact-based

knowledges”

or “back to basics” science education paradigms. These

have the shared result of losing

already marginalized students. Further,

their lack of science acumen keeps them from fully participating in the

global

community. All of the researchers

reviewed show how denying the students’ a way to access science

knowledge from

within cultural frameworks ensures student lack-of-interest and failure. Culturally open education, on the other hand,

results in students that experience science education efficacy. The more that a student feels that he/she is

an important part of the science classroom, and that science education

is

welcoming to him/her and his/her pathways of thought and understanding,

the

more that student will be successful in learning about, understanding

and using

science knowledge. The reality,

unfortunately, is that many districts approach science curriculum

development

through the former, rather than the latter, paradigm.

In my district the three “core” sciences

(General

Physical Science, Biology and Chemistry) have a district-wide

standardized

curriculum, based on state standards.

These curricula purport to be inquiry-based, but are

actually almost

purely knowledge-based. Further, they

are not based on more expansive, accessible and usable big ideas

(Leonard,

Gerace & Dufresne, 1999; Orkwiszewski, 2006), but individual sets

of facts

and skills-objectives. The following

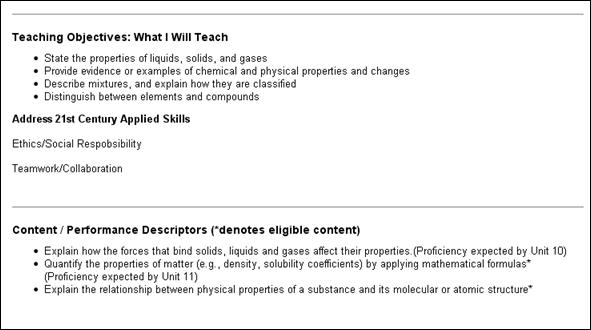

image is part of a screenshot taken of the second week of the chemistry

curriculum

(available online):

Even though the “21st

Century Applied Skills” to address are “Ethics/Social Responsibility”

and

“Teamwork/Collaboration”, the teaching objectives are all facts. The performance descriptors all describe

fact-related tasks to be accomplished.

The particularly important piece to note is that each

asterisked item is

something that is considered “eligible content,” meaning content that

will be

tested on the state standardized test.

What this means is that a teacher may WANT to allow the

student to be

part of the discourse of developing the language of liquids, solids and

gases,

or the description of physical properties, but if that discourse leads

to a

language that is different from the state’s language, even if it is

appropriate, it will be wrong. What will

then happen is the student will likely face the test question and think

that

what he learned is wrong, even if it isn’t.

Further pressure has

been added in the form of quarterly (and in subjects, weekly)

standardized

Benchmark Tests that are meant to establish whether the students are

“where

they are supposed to be” in the curriculum.

A teacher may WANT to be able to teach students how

catalytic converters

work, because he has a lot of car enthusiasts in the classroom, but if

it

doesn’t have a place in the curriculum, there isn’t time.

Instead, the teacher might be called upon to

force feed the memorization of ionic compound names, just to be sure

that it is

done before the test happens.

The Teacher Stands Alone

Unfortunately, the lack

of time and the pressure of administrators who are, themselves, under

pressure

from district, state and national mandates, creates an opposition of

priorities

(teach the student or teach the content) that forces the teacher into a

difficult decision, between the Scylla choice of ignoring the

administrative

mandates, at the risk of her job, and the Charybdis choice of ignoring

the

needs of her students, at the risk of her professionalism and her

students’

futures. The researchers that Dinghra

reviews know which side they fall on.

They all make clear the fact that the development of the

students’

learning experiences should be a process shared with, the students to

be

educated. Dinghra (2007) further

produces a list of actions that must be taken to insure that these

reforms take

place. Dinghra goes on to state that

assessment should be a process completed “side by side” with the

student.

These are all great suggestions, but are

moot if the

only one fighting for these reforms is the classroom teacher, and all

of the

administrators and decision-makers are moving in opposition. When the standardized weekly assessment

started, every one of my teachers came to me with their hands in the

air. “I am behind in the [Planning and

Scheduling

Timeline]. What am I supposed to do?”

one asked. “Either I skip the

presentations that my students have prepared and teach them this

material at

the last minute, or I give them a test on material they’ve never seen. Either way, they’ll be angry, upset and will

probably not do anything for the next month.” I

had no answer. When I asked regional

representatives for the

rationale behind the weekly test, it was made clear that the reason

they were

instituted was because the district administration did not think that

the teachers

were cleaving sufficiently to the district curriculum.

What can a reform-minded teacher do with

that?

Dinghra does assert that

it is not the burden of the school to move towards the suggested

reforms, but

goes on to say that school can help to pull on students’ experiences

through

providing experiences, such as field trips or after-school programs, or

acknowledging experiences as valid, such as television or video games. Again, however, what happens if the

experience through which the student understands a particular subject

does not

fit the standardized test? More often

than not, the student is not able to make the transfer of knowledge,

and gets

the question on the test wrong.

Here is my question to

Dhingra and the researchers reviewed: If

it is not the role the school, and the district administrators won’t

take on

that role, what can be done? Clearly,

legislation can force bad change. Can’t

it also force good? The researchers need

to come together to lobby the legislators.

I believe that then, and only then, will science knowledge

pursuit

become inclusive, rather than exclusive.

References

Dhingra, Koshi. (Nov 2007).

Towards science educational spaces as dynamic and

coauthored

communities of practice.

Cult

Stud of Sci Educ 3:123–144. Retrieved

January 12, 2009, from https://courseweb.library.upenn.edu/webapps/portal/frameset.jsp?tab_id=_2_1&

url=%2fwebapps%2fblackboard%2fexecute%2flauncher%3ftype%3dCourse%26id%3d_2893_1%26url%3d

Ennis, Catherine D. & McCauley, M. Terri. (2002) Creating urban classroom communities

worthy of trust. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 34(2), 149-172.

Liu, Xiufeng & Fulmer, Gavin. (April 2008). Alignment Between the Science Curriculum

and Assessment in Selected NY State Regents

Exams. Journal

of Science Education and Technology 17, 373-383.

Orkwiszewski.

(2006). Moving from didactic to

inquiry-based instruction. The

American

Biology Teacher, 68(6), 342-345.

School District of Philadelphia. (2008). Planning and Scheduling Timeline: Chemistry.

Philadelphia: Office of Teaching and Learning.

University of Massachusetts Physics Education Research Group: Department of Physics &

Astronomy and Scientific Reasoning Research Institute. (1999). Concept-Based Problem

Solving: Making concepts the language of physics. Amherst, Massachusetts: Leonard,

William J., Gerace, William J., & Dufresne, Robert J.